Peptic ulcer disease is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus.[1][7] An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines is a duodenal ulcer.[1] The most common symptoms of a duodenal ulcer are waking at night with upper abdominal pain, and upper abdominal pain that improves with eating.[1] With a gastric ulcer, the pain may worsen with eating.[8] The pain is often described as a burning or dull ache.[1] Other symptoms include belching, vomiting, weight loss, or poor appetite.[1] About a third of older people with peptic ulcers have no symptoms.[1] Complications may include bleeding, perforation, and blockage of the stomach.[2] Bleeding occurs in as many as 15% of cases.[2]

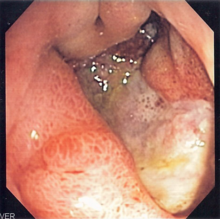

Common causes include infection with Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[1] Other, less common causes include tobacco smoking, stress as a result of other serious health conditions, Behçet's disease, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, Crohn's disease, and liver cirrhosis.[1][3] Older people are more sensitive to the ulcer-causing effects of NSAIDs.[1] The diagnosis is typically suspected due to the presenting symptoms with confirmation by either endoscopy or barium swallow.[1] H. pylori can be diagnosed by testing the blood for antibodies, a urea breath test, testing the stool for signs of the bacteria, or a biopsy of the stomach.[1] Other conditions that produce similar symptoms include stomach cancer, coronary heart disease, and inflammation of the stomach lining or gallbladder inflammation.[1]

Diet does not play an important role in either causing or preventing ulcers.[9] Treatment includes stopping smoking, stopping use of NSAIDs, stopping alcohol, and taking medications to decrease stomach acid.[1] The medication used to decrease acid is usually either a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or an H2 blocker, with four weeks of treatment initially recommended.[1] Ulcers due to H. pylori are treated with a combination of medications, such as amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and a PPI.[4] Antibiotic resistance is increasing and thus treatment may not always be effective.[4] Bleeding ulcers may be treated by endoscopy, with open surgery typically only used in cases in which it is not successful.[2]

Peptic ulcers are present in around 4% of the population.[1] New ulcers were found in around 87.4 million people worldwide during 2015.[5] About 10% of people develop a peptic ulcer at some point in their life.[10] Peptic ulcers resulted in 267,500 deaths in 2015, down from 327,000 in 1990.[6][11] The first description of a perforated peptic ulcer was in 1670, in Princess Henrietta of England.[2] H. pylori was first identified as causing peptic ulcers by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren in the late 20th century,[4] a discovery for which they received the Nobel Prize in 2005.[12]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Najm WI (September 2011). "Peptic ulcer disease". Primary Care. 38 (3): 383–94, vii. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.001. PMID 21872087.

- ^ a b c d e Milosavljevic T, Kostić-Milosavljević M, Jovanović I, Krstić M (2011). "Complications of peptic ulcer disease". Digestive Diseases. 29 (5): 491–3. doi:10.1159/000331517. PMID 22095016. S2CID 25464311.

- ^ a b Steinberg KP (June 2002). "Stress-related mucosal disease in the critically ill patient: risk factors and strategies to prevent stress-related bleeding in the intensive care unit". Critical Care Medicine. 30 (6 Suppl): S362–4. doi:10.1097/00003246-200206001-00005. PMID 12072662.

- ^ a b c d Wang AY, Peura DA (October 2011). "The prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori-associated peptic ulcer disease and upper gastrointestinal bleeding throughout the world". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 21 (4): 613–35. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.011. PMID 21944414.

- ^ a b "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM, Coggeshall M, Dandona L, Dicker DJ, Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fraser MS, Fullman N, Gething PW, Goldberg EM, Graetz N, Haagsma JA, Hay SI, Huynh C, Johnson CO, Kassebaum NJ, Kinfu Y, Kulikoff XR (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ "Definition and Facts for Peptic Ulcer Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Rao SD (2014). Clinical Manual of Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 526. ISBN 9788131238714.

- ^ "Eating, Diet, and Nutrition for Peptic Ulcer Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Snowden FM (October 2008). "Emerging and reemerging diseases: a historical perspective". Immunological Reviews. 225 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00677.x. PMC 7165909. PMID 18837773.

- ^ "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. January 2015. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2005". nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.