| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luminal, Sezaby, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682007 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High[1] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, rectal, parenteral[2][3] |

| Drug class | Barbiturate |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Protein binding | 20 to 45% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP2C19) |

| Onset of action | Within 5 min (IV); 30 min (PO)[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 53–118 hours |

| Duration of action | 4 hours–2 days[6][7] |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.007 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

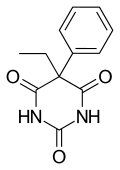

| Formula | C12H12N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 232.239 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, sold under the brand name Luminal among others, is a medication of the barbiturate type.[6] It is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of certain types of epilepsy in developing countries.[8] In the developed world, it is commonly used to treat seizures in young children,[9] while other medications are generally used in older children and adults.[10] It is also used for veterinary purposes.[11]

It may be administered by slow intravenous infusion (IV infusion), intramuscularly (IM), or orally (swallowed by mouth). Subcutaneous administration is not recommended.[6] The IV or IM (injectable forms) may be used to treat status epilepticus if other drugs fail to achieve satisfactory results.[6] Phenobarbital is occasionally used to treat insomnia, anxiety, and benzodiazepine withdrawal (as well as withdrawal from certain other drugs in specific circumstances), and prior to surgery as an anxiolytic and to induce sedation.[6] It usually begins working within five minutes when used intravenously and half an hour when administered orally.[6] Its effects last for between four hours and two days.[6][7]

Potentially serious side effects include a decreased level of consciousness and respiratory depressant.[6] There is potential for both abuse and withdrawal following long-term use.[6] It may also increase the risk of suicide.[6]

It is pregnancy category D in Australia, meaning that it may cause harm when taken during pregnancy.[6][12] If used during breastfeeding it may result in drowsiness in the baby.[13] Phenobarbital works by increasing the activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.[6]

Phenobarbital was discovered in 1912 and is the oldest still commonly used anti-seizure medication.[14][15] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[16]

- ^ Bassert JM (2017). McCurnin's Clinical Textbook for Veterinary Technicians - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 955. ISBN 9780323496407. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Hocker S, Clark S, Britton J (October 2018). "Parenteral phenobarbital in status epilepticus revisited: Mayo Clinic experience". Epilepsia. 59 Suppl 2: 193–197. doi:10.1111/epi.14488. PMID 30159873.

- ^ "Barbiturate (Oral Route, Parenteral Route, Rectal Route) Proper Use". Mayo Clinic. 7 August 2024. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Sezaby- phenobarbital sodium injection". DailyMed. 6 January 2023. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Phenobarbital". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b Marx JA (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice (7 ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1352. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Ilangaratne NB, Mannakkara NN, Bell GS, Sander JW (December 2012). "Phenobarbital: missing in action". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 90 (12): 871–871A. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.113183 (inactive 12 November 2024). PMC 3524964. PMID 23284189.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Brodie MJ, Kwan P (December 2012). "Current position of phenobarbital in epilepsy and its future". Epilepsia. 53 (Suppl 8): 40–46. doi:10.1111/epi.12027. PMID 23205961. S2CID 25553143.

- ^ National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) (January 2012). "The Epilepsies: The Diagnosis and Management of the Epilepsies in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care: Pharmacological Update of Clinical Guideline 20". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK). PMID 25340221. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022 – via PubMed.

- ^ Thomas WB (2003). "Seizures and narcolepsy". In Dewey CW (ed.). A Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press. ISBN 978-0-8138-1249-6.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Phenobarbital use while Breastfeeding". 2013. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Brenner GM, Stevens CW (2013). "Antiepileptic Drugs". Pharmacology (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-4557-0278-7. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017.

- ^ Engel J (2008). Epilepsy : a comprehensive textbook (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1431. ISBN 978-0-7817-5777-5. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.