| Philip the Arab | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

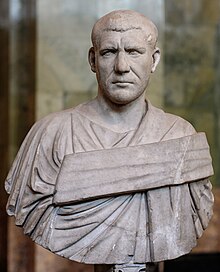

Bust of Philip I at The State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, 2010 | |||||||||

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||||||

| Reign | February 244 – September 249 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Gordian III | ||||||||

| Successor | Decius | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Philip II (248–249) | ||||||||

| Born | c. 204 Philippopolis, Arabia Petraea, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Died | September 249 (aged 45) Verona, Italia, Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||

| Issue | Philip II | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Julius Marinus | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman paganism (publicly) Christianity (speculated)[2] | ||||||||

Philip I (Latin: Marcus Julius Philippus; c. 204 – September 249), commonly known as Philip the Arab, was the Emperor of the Roman Empire from 244 to 249. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, who had been Praetorian prefect, rose to power. He quickly negotiated peace with the Sasanian Empire and returned to Rome to be confirmed by the Senate.

Although his reign lasted only five years, it marks an unusually stable period in a century that is otherwise known for having been turbulent.[a][b] Near the end of his rule, Philip commemorated Rome's first millennium. In September 249, during the Battle of Verona, he was betrayed and killed by Decius, who promptly usurped the throne before being recognized by the Senate as his successor.

Born in modern-day Shahba, Syria, in what was then Arabia Petraea, Philip's ethnicity was not attested with certainty, but he was most likely an Arab. While he publicly adhered to the Roman religion, he was later asserted to have been a Christian, and in the later half of the 3rd century and into the beginning of the 4th century, some Christian clergymen held that Philip had been the first Christian ruler of Rome. He was described as such in many published works that became widely known during the Middle Ages, including: Chronicon (lit. 'Chronicle'); Historiae Adversus Paganos (lit. 'History Against the Pagans'); and Historia Ecclesiastica (lit. 'Ecclesiastical History').[5] Consequently, Philip's religious affiliation remains a divisive topic in modern scholarly debate about his life.

- ^ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (15 December 2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- ^ Bowersock 1983, p. 124.

- ^ Ball 2000, p. 468.

- ^ Shahîd 1984, pp. 65–93.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).