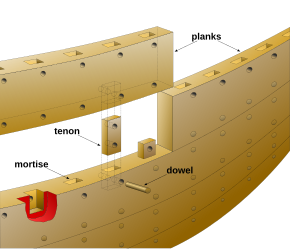

Phoenician joint with pegged mortise and tenon construction | |

| Industrial sector(s) | Woodworking, shipbuilding |

|---|---|

| Feedstock | Timber |

| Product(s) | Watercraft hulls secured with locked mortise and tenon joints |

| Inventor | The Phoenicians |

Phoenician joints (Latin: coagmenta punicana) is a locked mortise and tenon wood joinery technique used in shipbuilding to fasten watercraft hulls. The locked (or pegged) mortise and tenon technique consists of cutting a mortise, or socket, into the edges of two planks and fastening them together with a rectangular wooden knob. The assembly is then locked in place by driving a dowel through one or more holes drilled through the mortise side wall and tenon.

The Phoenicians pioneered the use of locked mortise and tenon joints in nautical joinery to secure the underwater planking of seagoing ships. The use of pegged mortises and tenons in shipbuilding spread westward from the Levantine littoral. Examples of the use of Phoenician joints in the ancient Mediterranean include the Uluburun ship, dated c. 1320±50 BC, and the Cape Gelidonya ship dated to c. 1200 BC.

By the first millennium BC, Phoenician joints became a common edge-to-edge fastening method. Ancient Greek and Roman shipbuilders adopted the technique of Phoenician joinery. Roman writers credited the joinery technique to Phoenicians by calling it coagmenta punicana or Punicanis coamentis. The ancient Greek historian Polybius reported that the Romans copied the locked mortise and tenon technique from a Punic warship that ran aground in 264 BC. They exploited this technique to their advantage early in the First Punic War in 260 BC which allowed them to build a fleet of 100 quinqueremes within a period of two months.

One factor contributing to their success was the abundance of cedar forests in their territory. These forests provided them with a steady supply of high-quality timber, a crucial resource for shipbuilding[1] This access to timber enabled the Phoenicians to construct large seafaring vessels capable of carrying hundreds of people. Due to the amount of timber they were producing, logs were brought onto the ship for trade, bringing them to other civilizations in exchange goods such as gold and tin.[2][page needed] These forested mountains, documented by ancient writers such as Homer, Pliny, and Plato, as well as the Old Testament, provided the Phoenicians with a large supply of high-quality cedar wood. Cedar was particularly prized for its strength, durability, and resistance to rot, making it ideal for shipbuilding.[3][full citation needed] These ships, often depicted with rows of oars on either side, facilitated long-distance travel and trade across the Mediterranean Sea and beyond.[citation needed]