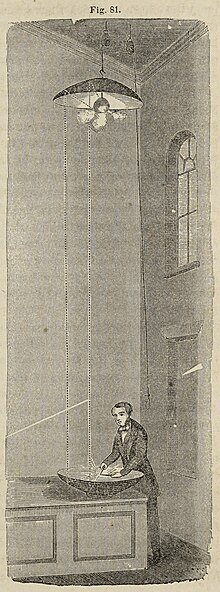

Pictet's experiment is the demonstration of the reflection of heat and the apparent reflection of cold in a series of experiments[1] performed in 1790 (reported in English in 1791 in An Essay on Fire[2]) by Marc-Auguste Pictet—ten years before the discovery of infrared heating of the Earth by the Sun.[3] The apparatus for most of the experiments used two concave mirrors facing one another at a distance. An object placed at the focus of one mirror would have heat and light reflected by the mirror and focused. An object at the focus of the counterpart mirror would do the same. Placing a hot object at one focus and a thermometer at the other would register an increase in temperature on the thermometer. This was sometimes demonstrated with the explosion of a flammable mix of gasses in a blackened balloon, as described and depicted by John Tyndall in 1863.[4]

After "demonstrating that radiant heat, even when it was not accompanied by any light, could be reflected and focused like light",[5] Pictet used the same apparatus to demonstrate the apparent reflection of cold[6] in a similar manner. This demonstration was important to Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford who argued for the existence of "frigorific rays" conveying cold. Rumford's continuation of the experiments[7] and promotion of the topic[8] caused the name to be attached to the experiment.[9]

The apparent reflection of cold if a cold object is placed in one focus surprised Pictet[10] and two scholars writing about the experiment in 1985 noted "most physicists, on seeing it demonstrated for the first time, find it surprising and even puzzling."[11] The confusion may be resolved by understanding that all objects in the system—including the thermometer—are constantly radiating heat. Pictet described this as "the thermometer acts the same part relatively to the snow as the bullet [heat source] in relation to the thermometer." Addition of a very cold object adds an effective heat sink versus a room temperature object which would not, in the net, cool or warm a thermometer in the other focus.[12]

- ^ Evans, James; Popp, Brian (1985). "Pictet's experiment: The apparent radiation and reflection of cold" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 53 (8): 737–753. Bibcode:1985AmJPh..53..737E. doi:10.1119/1.14305.

- ^ An essay on fire : By Mark Augustus Pictet Translated from the French, under the inspection of the author, by W.B.M.D. London: E. Jeffery. 1791. pp. 86–87, 117–123. OCLC 85869483.

- ^ Herschel, William (1800). "Experiments on the refrangibility of the invisible rays of the Sun". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 90: 284–292. doi:10.1098/rstl.1800.0015. JSTOR 107057.

- ^ Tyndall, John (1863). Heat considered as a mode of motion: being a course of twelve lectures delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in the season of 1862. New York: D. Appleton & co. p. 281.

- ^ Chang, Hasok (May 2002). "Rumford and the Reflection of Radiant Cold: Historical Reflections and Metaphysical Reflexes". Physics in Perspective. 4 (2): 132. Bibcode:2002PhP.....4..127C. doi:10.1007/s00016-002-8362-8. ISSN 1422-6944. S2CID 120270510.

- ^ Tyndall, John (1863). Heat considered as a mode of motion: being a course of twelve lectures delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in the season of 1862. New York State: D. Appleton. pp. 281–282. OCLC 1297049.

- ^ Chang, Hasok (2007). Inventing temperature: measurement and scientific progress. Oxford studies in philosophy of science (1. issued as paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-533738-9.

- ^ Brown, Sanborn C. (1952-09-01). "Count Rumford's Concept of Heat". American Journal of Physics. 20 (6): 332–333. Bibcode:1952AmJPh..20..331B. doi:10.1119/1.3416888. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ Evans, James; Popp, Brian (1985-08-01). "Pictet's experiment: The apparent radiation and reflection of cold". American Journal of Physics. 53 (8): 741. Bibcode:1985AmJPh..53..737E. doi:10.1119/1.14305. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ Chang, Hasok (2007). Inventing temperature: measurement and scientific progress. Oxford studies in philosophy of science (1. issued as paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-533738-9.

- ^ Evans, James; Popp, Brian (1985-08-01). "Pictet's experiment: The apparent radiation and reflection of cold". American Journal of Physics. 53 (8): 738. Bibcode:1985AmJPh..53..737E. doi:10.1119/1.14305. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ Lemons, Don Stephen; Shanahan, William R.; Buchholtz, Louis (2022). On the trail of blackbody radiation: Max Planck and the physics of his era. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-262-04704-3.