Divergent:

| Part of a series on |

| Geology |

|---|

|

Plate tectonics (from Latin tectonicus, from Ancient Greek τεκτονικός (tektonikós) 'pertaining to building')[1] is the scientific theory that Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago.[2][3][4] The model builds on the concept of continental drift, an idea developed during the first decades of the 20th century. Plate tectonics came to be accepted by geoscientists after seafloor spreading was validated in the mid-to-late 1960s. The processes that result in plates and shape Earth's crust are called tectonics. Tectonic plates also occur in other planets and moons.

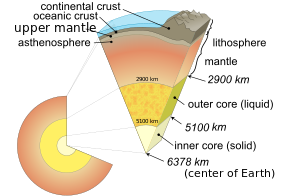

Earth's lithosphere, the rigid outer shell of the planet including the crust and upper mantle, is fractured into seven or eight major plates (depending on how they are defined) and many minor plates or "platelets". Where the plates meet, their relative motion determines the type of plate boundary (or fault): convergent, divergent, or transform. The relative movement of the plates typically ranges from zero to 10 cm annually.[5] Faults tend to be geologically active, experiencing earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation.

Tectonic plates are composed of the oceanic lithosphere and the thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent plate boundaries, the process of subduction carries the edge of one plate down under the other plate and into the mantle. This process reduces the total surface area (crust) of the Earth. The lost surface is balanced by the formation of new oceanic crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading, keeping the total surface area constant in a tectonic "conveyor belt".

Tectonic plates are relatively rigid and float across the ductile asthenosphere beneath. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection currents, the slow creeping motion of Earth's solid mantle. At a seafloor spreading ridge, plates move away from the ridge, which is a topographic high, and the newly formed crust cools as it moves away, increasing its density and contributing to the motion. At a subduction zone the relatively cold, dense oceanic crust sinks down into the mantle, forming the downward convecting limb of a mantle cell,[6] which is the strongest driver of plate motion.[7][8] The relative importance and interaction of other proposed factors such as active convection, upwelling inside the mantle, and tidal drag of the Moon is still the subject of debate.

- ^ Little, Fowler & Coulson 1990.

- ^ Dhuime, B; Hawkesworth, CJ; Cawood, PA; Storey, CD (2012). "A change in the geodynamics of continental growth 3 billion years ago". Science. 335 (6074): 1334–1336. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1334D. doi:10.1126/science.1216066. PMID 22422979. S2CID 206538532.

- ^ Harrison, TM (2009). "The Hadean crust: evidence from> 4 Ga zircons". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37 (1): 479–505. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37..479H. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100151.

- ^ Windley, BF; Kusky, T; Polat, A (2021). "Onset of plate tectonics by the Eoarchean". Precambrian Research. 352: 105980. Bibcode:2021PreR..35205980W. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2020.105980. S2CID 228993361.

- ^ Read & Watson 1975.

- ^ Stern, Robert J. (2002). "Subduction zones". Reviews of Geophysics. 40 (4): 1012. Bibcode:2002RvGeo..40.1012S. doi:10.1029/2001RG000108. S2CID 247695067.

- ^ Forsyth, D.; Uyeda, S. (1975). "On the Relative Importance of the Driving Forces of Plate Motion". Geophysical Journal International. 43 (1): 163–200. Bibcode:1975GeoJ...43..163F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1975.tb00631.x.

- ^ Conrad & Lithgow-Bertelloni 2002.