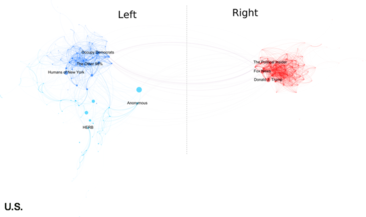

Political polarization is a prominent component of politics in the United States.[1] Scholars distinguish between ideological polarization (differences between the policy positions) and affective polarization (a dislike and distrust of political out-groups), both of which are apparent in the United States.[2][3][4] In the last few decades, the U.S. has experienced a greater surge in ideological polarization and affective polarization than comparable democracies.[5]

Differences in political ideals and policy goals are indicative of a healthy democracy.[6] Scholarly questions consider changes in the magnitude of political polarization over time, the extent to which polarization is a feature of American politics and society,[7] and whether there has been a shift away from focusing on triumphs to dominating the perceived abhorrent supporters of the opposing party.[6]

Polarization among U.S. legislators is asymmetric, as it has primarily been driven by a rightward shift among Republicans in Congress.[8][9][10][11] Polarization has increased since the 1970s, with rapid increases in polarization during the 2000s onwards.[12] According to the Pew Research Center, members of both parties who have unfavorable opinions of the opposing party have doubled since 1994,[13] while those who have very unfavorable opinions of the opposing party are at record highs as of 2022.[14]

- ^ Heltzel, Gordon; Laurin, Kristin (August 2020). "Polarization in America: two possible futures". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 34: 179–184. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.008. ISSN 2352-1546. PMC 7201237. PMID 32391408.

- ^ Iyengar, Shanto; Lelkes, Yphtach; Levendusky, Matthew; Malhotra, Neil; Westwood, Sean J. (2019). "The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States". Annual Review of Political Science. 22 (1): 129–146. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034. ISSN 1094-2939. S2CID 102523958.

- ^ Iyengar, Shanto (2022), Sibley, Chris G.; Osborne, Danny (eds.), "Fear and Loathing in American Politics: A Review of Affective Polarisation", The Cambridge Handbook of Political Psychology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 399–413, ISBN 978-1-108-48963-8

- ^ Finkel, Eli J.; Bail, Christopher A.; Cikara, Mina; Ditto, Peter H.; Iyengar, Shanto; Klar, Samara; Mason, Lilliana; McGrath, Mary C.; Nyhan, Brendan; Rand, David G.; Skitka, Linda J.; Tucker, Joshua A.; Van Bavel, Jay J.; Wang, Cynthia S.; Druckman, James N. (October 30, 2020). "Political sectarianism in America". Science. 370 (6516): 533–536. doi:10.1126/science.abe1715. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33122374.

- ^ Boxell, Levi; Gentzkow, Matthew; Shapiro, Jesse M. (2022). "Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 106 (2): 557–565. doi:10.1162/rest_a_01160. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 246583807.

- ^ a b Finkel, Eli J.; Bail, Christopher A.; Cikara, Mina; Ditto, Peter H.; Iyengar, Shanto; Klar, Samara; Mason, Lilliana; McGrath, Mary C.; Nyhan, Brendan; Rand, David G.; Skitka, Linda J. (October 30, 2020). "Political sectarianism in America". Science. 370 (6516): 533–536. doi:10.1126/science.abe1715. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33122374.

- ^ Pierson, Paul; Schickler, Eric (2020). "Madison's Constitution Under Stress: A Developmental Analysis of Political Polarization". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 37–58. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033629.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:12was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:13was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Moskowitz, Daniel J.; Rogowski, Jon C.; Jr, James M. Snyder (2024). "Parsing Party Polarization in Congress". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 19 (4): 357–385. doi:10.1561/100.00022039. ISSN 1554-0626.

- ^ DeSilver, Drew (March 10, 2022). "The polarization in today's Congress has roots that go back decades". Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Grumbach, Jacob M. (2018). "From Backwaters to Major Policymakers: Policy Polarization in the States, 1970–2014". Perspectives on Politics. 16 (2): 416–435. doi:10.1017/S153759271700425X. ISSN 1537-5927.

- ^ Doherty, Carroll (June 17, 2014). "Which party is more to blame for political polarization? It depends on the measure". Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ "How Democrats and Republicans see each other". The Economist. August 17, 2022. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved August 18, 2022.