IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: ESO/P. Kervella

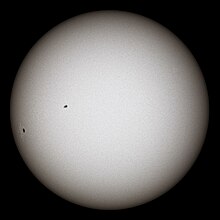

Betelgeuse is a semiregular variable star located approximately 640 light-years from the Earth. With an apparent magnitude ranging between 0.3 and 1.2, it is the ninth brightest star in the night sky. Although Betelgeuse has the Bayer designation Alpha Orionis (α Orionis / α Ori), it is most often the second brightest star in the constellation Orion behind α; Rigel (Beta Orionis) is usually brighter (Betelgeuse is a variable star and is on occasion brighter than Rigel). The star marks the upper right vertex of the Winter Triangle and center of the Winter Hexagon. Betelgeuse is a red supergiant, and one of the largest and most luminous stars known. For comparison, if the star were at the center of the Solar System its surface might extend out to between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, wholly engulfing Mercury, Venus, the Earth and Mars. The angular diameter of Betelgeuse was first measured in 1920–1921 by Albert Abraham Michelson and Francis G. Pease using the 100 inch (2.5 m) John D. Hooker astronomical interferometer telescope atop Mount Wilson Observatory. Astronomers believe Betelgeuse is only a few million years old, but has evolved rapidly because of its high mass. Due to its age, Betelgeuse may go supernova within the next millennium (because it is hundreds of light years away, it possibly may have done so already). Selected article - Photo credit: User:Alain r

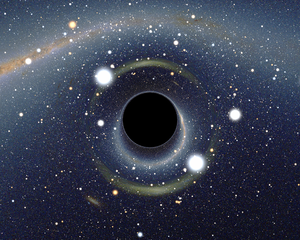

According to the general theory of relativity, a black hole is a region of space from which nothing, including light, can escape. It is the result of the deformation of spacetime caused by a very compact mass. Around a black hole there is an undetectable surface which marks the point of no return, called an event horizon. It is called "black" because it absorbs all the light that hits it, reflecting nothing, just like a perfect black body in thermodynamics. Under the theory of quantum mechanics black holes possess a temperature and emit Hawking radiation. Despite its invisible interior, a black hole can be observed through its interaction with other matter. A black hole can be inferred by tracking the movement of a group of stars that orbit a region in space. Alternatively, when gas falls into a stellar black hole from a companion star, the gas spirals inward, heating to very high temperatures and emitting large amounts of radiation that can be detected from earthbound and Earth-orbiting telescopes. Astronomers have identified numerous stellar black hole candidates, and have also found evidence of supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies. After observing the motion of nearby stars for 16 years, in 2008 astronomers found compelling evidence that a supermassive black hole of more than 4 million solar masses is located near the Sagittarius A* region in the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA/TRACE

In astronomy, stellar classification is a classification of stars based on their spectral characteristics. The spectral class of a star is a designated class of a star describing the ionization of its chromosphere, what atomic excitations are most prominent in the light, giving an objective measure of the temperature in this chromosphere. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

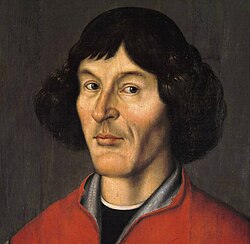

Selected biography - Photo credit: Portrait from Toruń

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was the first astronomer to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology, which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe. Nicolaus Copernicus was born on 19 February 1473 in the city of Toruń (Thorn) in Royal Prussia, part of the Kingdom of Poland. Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published just before his death in 1543, is often regarded as the starting point of modern astronomy and the defining epiphany that began the scientific revolution. His heliocentric model, with the Sun at the center of the universe, demonstrated that the observed motions of celestial objects can be explained without putting Earth at rest in the center of the universe. His work stimulated further scientific investigations, becoming a landmark in the history of science that is often referred to as the Copernican Revolution. Among the great polymaths of the Renaissance, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, physician, quadrilingual polyglot, classical scholar, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, jurist, governor, military leader, diplomat and economist. Among his many responsibilities, astronomy figured as little more than an avocation – yet it was in that field that he made his mark upon the world.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |