Guarded Domains of Iran | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1789–1925 | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: (1873–1909) Salâm-e Shâh (Royal salute) (1909–1925) Salamati-ye Dowlat-e 'Aliyye-ye Iran (Salute of the Sublime State of Iran) | |||||||||||||

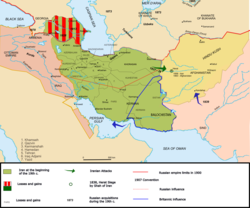

Map of Iran under the Qajar dynasty in the 19th century. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Tehran | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam (official) minority religions: Sunni Islam, Sufism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Baháʼí Faith, Mandaeism | ||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||

| Shah | |||||||||||||

• 1789–1797 (first) | Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar | ||||||||||||

• 1909–1925 (last) | Ahmad Shah Qajar | ||||||||||||

• 1795-1801 (first) | Hajji Ebrahim Shirazi | ||||||||||||

• 1923–1925 (last) | Reza Pahlavi | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | None (until 1906; 1907–1909) National Consultative Assembly (1906–1907; from 1909) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Establishment | 1789 | ||||||||||||

| 24 October 1813 | |||||||||||||

| 10 February 1828 | |||||||||||||

| 4 March 1857 | |||||||||||||

| 21 September 1881 | |||||||||||||

| 5 August 1906 | |||||||||||||

| December 27, 1915 | |||||||||||||

• Deposed by Constituent Assembly | 31 October 1925 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | toman (1789–1825) qiran (1825–1925)[6] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Guarded Domains of Iran,[a] alternatively the Sublime State of Iran[b] and commonly called Qajar Iran, Qajar Persia or the Qajar Empire, was the Iranian state[7] under the rule of the Qajar dynasty, which was of Turkic origin,[8][9][10] specifically from the Qajar tribe, from 1789 to 1925.[7][11] The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease,[12] putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty. He was formally crowned as Shah after his punitive campaign against Iran's Georgian subjects.[13]

In the Caucasus, the Qajar dynasty permanently lost much territory[14] to the Russian Empire over the course of the 19th century, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.[15] Despite its territorial losses, Qajar Iran reinvented the Iranian notion of kingship[16] and maintained relative political independence, but faced major challenges to its sovereignty, predominantly from the Russian and British empires. Foreign advisers became powerbrokers in the court and military. They eventually partitioned Qajar Iran in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, carving out Russian and British influence zones and a neutral zone.[17][18][19]

In the early 20th century, the Persian Constitutional Revolution created an elected parliament or Majles, and sought the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, deposing Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar for Ahmad Shah Qajar, but many of the constitutional reforms were reversed by an intervention led by the Russian Empire.[17][20] Qajar Iran's territorial integrity was further weakened during the Persian campaign of World War I and the invasion by the Ottoman Empire. Four years after the 1921 Persian coup d'état, the military officer Reza Shah took power in 1925, thus establishing the Pahlavi dynasty, the last Iranian royal dynasty.

- ^ Homa Katouzian, State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis, published by I. B. Tauris, 2006. pg 327: "In post-Islamic times, the mother-tongue of Iran's rulers was often Turkic, but Persian was almost invariably the cultural and administrative language."

- ^ Katouzian 2007, p. 128.

- ^ "Ardabil Becomes a Province: Center-Periphery Relations in Iran", H. E. Chehabi, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 29, No. 2 (May, 1997), 235; "Azeri Turkish was widely spoken at the two courts in addition to Persian, and Mozaffareddin Shah (r. 1896–1907) spoke Persian with an Azeri Turkish accent."

- ^ Javadi & Burrill 1988, pp. 251–255.

- ^ Donzel, Emeri "van" (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. ISBN 90-04-09738-4. p. 285-286

- ^ علیاصغر شمیم، ایران در دوره سلطنت قاجار، تهران: انتشارات علمی، ۱۳۷۱، ص ۲۸۷

- ^ a b Amanat 1997, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Cyrus Ghani. Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power, I. B. Tauris, 2000, ISBN 1-86064-629-8, p. 1

- ^ William Bayne Fisher. Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 344, ISBN 0-521-20094-6

- ^ Dr Parviz Kambin, A History of the Iranian Plateau: Rise and Fall of an Empire, Universe, 2011, p.36, online edition.

- ^ Choueiri, Youssef M., A companion to the history of the Middle East, (Blackwell Ltd., 2005), 231,516.

- ^ H. Scheel; Jaschke, Gerhard; H. Braun; Spuler, Bertold; T. Koszinowski; Bagley, Frank (1981). Muslim World. Brill Archive. pp. 65, 370. ISBN 978-90-04-06196-5. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Michael Axworthy. Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day, Penguin UK, 6 November 2008. ISBN 0141903414

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 330.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling. Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond, pp 728–730 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 177.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:13was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:92was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "ANGLO-RUSSIAN CONVENTION OF 1907". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:142was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).