| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

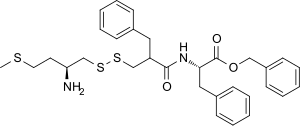

| Other names | RB-101; phenylmethyl (2S)-2-[(2-([(2S)-2-amino-4-methylsulfanylbutyl]disulfanylmethyl)-3-phenylpropanoyl)amino]-3-phenylpropanoate |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C31H38N2O3S3 |

| Molar mass | 582.84 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

RB-101 is a drug that acts as an enkephalinase inhibitor, which is used in scientific research.

RB-101 is a prodrug which acts by splitting at the disulfide bond once inside the brain, to form two selective enzyme inhibitors and blocking both types of the zinc-metallopeptidase enkephalinase enzymes. This inhibits the breakdown of the endogenous opioid peptides known as enkephalins.[1] These two enzymes, aminopeptidase N (APN) and neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (NEP), are responsible for the breakdown of both kinds of enkephalin naturally found in the body, and so RB-101 causes a buildup of both Met-enkephalin and Leu-enkephalin.[2][3]

These peptides act primarily at the delta opioid receptor, although they also stimulate the mu opioid receptor to some extent through a delta-opioid receptor mediated interaction with another peptide cholecystokinin, and the enzyme-inhibiting effects of RB-101 thus produce indirect stimulation of both of these opioid receptor subtypes.[4] This causes RB-101 to be strongly synergistic with cholecystokinin antagonists, such as proglumide.[5][6]

Unlike the more commonly used enkephalinase inhibitor racecadotril, which only acts peripherally and has antidiarrheal effects, RB-101 is able to enter the brain, and thus produces a range of effects, acting as an analgesic, anxiolytic and antidepressant.[7] The antidepressant and anxiolytic actions are thought to be mediated through the delta opioid receptor, while the analgesic effects most likely result from a mix of mu and delta activity.[8] Animal studies suggest that RB-101 is also likely to be useful in relieving the symptoms of acute opioid withdrawal[9] and in the management of opioid dependence.[10][11][12]

A significant advantage of inhibiting the breakdown of endogenous opioid peptides rather than stimulating opioid receptors with exogenous drugs is that the levels of opioid peptides are only increased slightly from natural levels, thus avoiding overstimulation and downregulation of the opioid receptors. This means that even when RB-101 is used in high doses for extended periods of time, there is no development of dependence on the drug or tolerance to its analgesic effects.[13][14] Consequently, even though RB-101 is able to produce potent analgesic effects via the opioid system, it is unlikely to be addictive.[15][16]

Unlike conventional opioid agonists, RB-101 also failed to produce respiratory depression, which suggests it might be a much safer drug than traditional opioid painkillers.[17] RB-101 also powerfully potentiated the effects of traditional analgesics such as ibuprofen and morphine, suggesting that it could be used to boost the action of a low dose of normal opioids which would otherwise be ineffective.[18]

RB-101 itself is not orally active and so has not been developed for medical use in humans, however modification of the drug has led to newer orally acting compounds such as RB-120 and RB-3007, which may be more likely to be adopted for medical use if clinical trials are successful.[19][20][21][22][23]

- ^ Roques BP (April 1992). "Peptidomimetics as receptors agonists or peptidase inhibitors: A structural approach in the field of enkephalins, ANP and CCK". Biopolymers. 32 (4): 407–10. doi:10.1002/bip.360320417. PMID 1320419.

- ^ Noble F, Soleilhac JM, Soroca-Lucas E, Turcaud S, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (April 1992). "Inhibition of the enkephalin-metabolizing enzymes by the first systemically active mixed inhibitor prodrug RB 101 induces potent analgesic responses in mice and rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 261 (1): 181–90. PMID 1560364.

- ^ Fournié-Zaluski MC, Coric P, Turcaud S, Lucas E, Noble F, Maldonado R, et al. (Jun 1992). "Mixed inhibitor-prodrug" as a new approach toward systemically active inhibitors of enkephalin-degrading enzymes". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 35 (13): 2473–81. doi:10.1021/jm00091a016. PMID 1352352.

- ^ Noble F, Smadja C, Roques BP (December 1994). "Role of endogenous cholecystokinin in the facilitation of mu-mediated antinociception by delta-opioid agonists". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 271 (3): 1127–34. PMID 7996417.

- ^ Valverde O, Maldonado R, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (July 1994). "Cholecystokinin B antagonists strongly potentiate antinociception mediated by endogenous enkephalins". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 270 (1): 77–88. PMID 8035345.

- ^ Honore P, Buritova J, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP, Besson JM (April 1997). "Antinociceptive effects of RB101, a complete inhibitor of enkephalin-catabolizing enzymes, are enhanced by a cholecystokinin type B receptor antagonist, as revealed by noxiously evoked spinal c-Fos expression in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 281 (1): 208–17. PMID 9103499.

- ^ Jutkiewicz EM, Torregrossa MM, Sobczyk-Kojiro K, et al. (February 2006). "Behavioral and neurobiological effects of the enkephalinase inhibitor RB101 relative to its antidepressant effects". European Journal of Pharmacology. 531 (1–3): 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.002. PMC 1828120. PMID 16442521.

- ^ Jutkiewicz EM (2007). "RB101-mediated Protection of Endogenous Opioids: Potential Therapeutic Utility?" (PDF). CNS Drug Reviews. 13 (2): 192–205. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00011.x. PMC 6726351. PMID 17627672.

- ^ Maldonado R, Valverde O, Ducos B, Blommaert AG, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (March 1995). "Inhibition of morphine withdrawal by the association of RB 101, an inhibitor of enkephalin catabolism, and the CCKB antagonist PD-134,308". British Journal of Pharmacology. 114 (5): 1031–9. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13309.x. PMC 1510310. PMID 7780637.

- ^ Ruiz F, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP, Maldonado R (September 1996). "Similar decrease in spontaneous morphine abstinence by methadone and RB 101, an inhibitor of enkephalin catabolism". British Journal of Pharmacology. 119 (1): 174–82. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15691.x. PMC 1915744. PMID 8872371.

- ^ Roques BP, Noble F (November 1996). "Association of enkephalin catabolism inhibitors and CCK-B antagonists: a potential use in the management of pain and opioid addiction". Neurochemical Research. 21 (11): 1397–410. doi:10.1007/bf02532381. PMID 8947930.

- ^ Cordonnier L, Sanchez M, Roques BP, Noble F (May 2007). "Blockade of morphine-induced behavioral sensitization by a combination of amisulpride and RB101, comparison with classical opioid maintenance treatments". British Journal of Pharmacology. 151 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707195. PMC 2012985. PMID 17351659.

- ^ Noble F, Turcaud S, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (November 1992). "Repeated systemic administration of the mixed inhibitor of enkephalin-degrading enzymes, RB101, does not induce either antinociceptive tolerance or cross-tolerance with morphine". European Journal of Pharmacology. 223 (1): 83–9. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(92)90821-K. PMID 1478260.

- ^ Noble F, Coric P, Turcaud S, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (March 1994). "Assessment of physical dependence after continuous perfusion into the rat jugular vein of the mixed inhibitor of enkephalin-degrading enzymes, RB 101". European Journal of Pharmacology. 253 (3): 283–7. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90203-8. PMID 8200422.

- ^ Noble F, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP (January 1993). "Unlike morphine the endogenous enkephalins protected by RB101 are unable to establish a conditioned place preference in mice". European Journal of Pharmacology. 230 (2): 139–49. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(93)90796-K. PMID 8422896.

- ^ Stein C, ed. (1999). Opioids in pain control : basic and clinical aspects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521622691.

- ^ Boudinot E, Morin-Surun M, Foutz AS, Fournié-Zaluski M, Roques BP, Denavit-Saubié M (February 2001). "Effects of the potent analgesic enkephalin-catabolizing enzyme inhibitors RB101 and kelatorphan on respiration". Pain. 90 (1–2): 7–13. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00382-1. PMID 11166965.

- ^ Nieto MM, Wilson J, Walker J, Benavides J, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP, et al. (September 2001). "Facilitation of enkephalins catabolism inhibitor-induced antinociception by drugs classically used in pain management". Neuropharmacology. 41 (4): 496–506. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(01)00077-6. PMID 11543770.

- ^ Noble F, Smadja C, Valverde O, Maldonado R, Coric P, Turcaud S, et al. (December 1997). "Pain-suppressive effects on various nociceptive stimuli (thermal, chemical, electrical and inflammatory) of the first orally active enkephalin-metabolizing enzyme inhibitor RB 120". Pain. 73 (3): 383–391. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00125-5. PMID 9469529.

- ^ Le Guen S, Mas Nieto M, Canestrelli C, Chen H, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Cupo A, et al. (July 2003). "Pain management by a new series of dual inhibitors of enkephalin degrading enzymes: long lasting antinociceptive properties and potentiation by CCK2 antagonist or methadone". Pain. 104 (1–2): 139–148. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00486-4. PMID 12855323.

- ^ Le Guen S, Mas Nieto M, Canestrelli C, Chen H, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Cupo A, et al. (July 2003). "Pain management by a new series of dual inhibitors of enkephalin degrading enzymes: long lasting antinociceptive properties and potentiation by CCK2 antagonist or methadone". Pain. 104 (1–2): 139–148. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00486-4. PMID 12855323.

- ^ Noble F, Roques BP (February 2007). "Protection of endogenous enkephalin catabolism as natural approach to novel analgesic and antidepressant drugs". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 11 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1517/14728222.11.2.145. PMID 17227231.

- ^ Thanawala V, Kadam VJ, Ghosh R (October 2008). "Enkephalinase inhibitors: potential agents for the management of pain". Current Drug Targets. 9 (10): 887–894. doi:10.2174/138945008785909356. PMID 18855623.