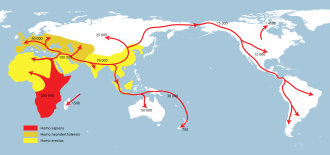

Homo erectus greatest extent (yellow)

Homo neanderthalensis greatest extent (ochre)

Homo sapiens (red)

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA)[a] is the most widely accepted[1][2][3] model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). It follows the early expansions of hominins out of Africa, accomplished by Homo erectus and then Homo neanderthalensis.

The model proposes a "single origin" of Homo sapiens in the taxonomic sense, precluding parallel evolution in other regions of traits considered anatomically modern,[4] but not precluding multiple admixture between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Europe and Asia.[b][5][6] H. sapiens most likely developed in the Horn of Africa between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago,[7][8] although an alternative hypothesis argues that diverse morphological features of H. sapiens appeared locally in different parts of Africa and converged due to gene flow between different populations within the same period.[9][10] The "recent African origin" model proposes that all modern non-African populations are substantially descended from populations of H. sapiens that left Africa after that time.

There were at least several "out-of-Africa" dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, including 215,000 years ago to at least Greece,[11][12][13] and certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago.[20] There is evidence that modern humans had reached China around 80,000 years ago.[21] Practically all of these early waves seem to have gone extinct or retreated back, and present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion about 70,000–50,000 years ago,[22][23][24][7][8][25][26][excessive citations] via the so-called "Southern Route". These humans spread rapidly along the coast of Asia and reached Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago,[27][28][c] (though some researchers question the earlier Australian dates and place the arrival of humans there at 50,000 years ago at earliest,[29][30] while others have suggested that these first settlers of Australia may represent an older wave before the more significant out of Africa migration and thus not necessarily be ancestral to the region's later inhabitants[24]) while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.[31][32][33]

In the 2010s, studies in population genetics uncovered evidence of interbreeding that occurred between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Eurasia, Oceania and Africa,[34][35][36] indicating that modern population groups, while mostly derived from early H. sapiens, are to a lesser extent also descended from regional variants of archaic humans.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid16826514Quowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid12802315was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stringer C (2012). Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth. Henry Holt and Company. p. 26. ISBN 978-1429973441 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid10766948was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Mafessoni F (January 2019). "Encounters with archaic hominins". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 14–15. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0729-6. PMID 30478304. S2CID 53783648.

- ^ Villanea FA, Schraiber JG (January 2019). "Multiple episodes of interbreeding between Neanderthal and modern humans". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0735-8. PMC 6309227. PMID 30478305.

- ^ a b University of Huddersfield (20 March 2019). "Researchers shed new light on the origins of modern humans – The work, published in Nature, confirms a dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b Rito T, Vieira D, Silva M, Conde-Sousa E, Pereira L, Mellars P, et al. (March 2019). "A dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 4728. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.4728R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41176-3. PMC 6426877. PMID 30894612.

- ^ Scerri EM, Chikhi L, Thomas MG (October 2019). "Beyond multiregional and simple out-of-Africa models of human evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (10): 1370–1372. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1370S. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0992-1. hdl:10400.7/954. PMID 31548642. S2CID 202733639.

- ^ Scerri EM, Thomas MG, Manica A, Gunz P, Stock JT, Stringer C, et al. (August 2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (8): 582–594. Bibcode:2018TEcoE..33..582S. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005. PMC 6092560. PMID 30007846.

- ^ Zimmer C (10 July 2019). "A Skull Bone Discovered in Greece May Alter the Story of Human Prehistory – The bone, found in a cave, is the oldest modern human fossil ever discovered in Europe. It hints that humans began leaving Africa far earlier than once thought". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Staff (10 July 2019). "'Oldest remains' outside Africa reset human migration clock". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Harvati K, Röding C, Bosman AM, Karakostis FA, Grün R, Stringer C, et al. (July 2019). "Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia". Nature. 571 (7766): 500–504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z. PMID 31292546. S2CID 195873640.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid21273486was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid21212332was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid21601174was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid17372199was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD (December 2017). "On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives". Science. 358 (6368): eaai9067. doi:10.1126/science.aai9067. PMID 29217544.

- ^ Kuo L (10 December 2017). "Early humans migrated out of Africa much earlier than we thought". Quartz. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ [14][15][16][17][18][19]

- ^ Liu, Martinón-Torres et al. (2015).

See also Modern humans in China ~80,000 years ago (?), Dieneks' Anthropology Blog. - ^ Finlayson (2009), p. 68.

- ^ Liu, Prugnolle et al. (2006).

- ^ a b Haber M, Jones AL, Connell BA, Arciero E, Yang H, Thomas MG, et al. (August 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-Chromosomal Haplogroup and Its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics. 212 (4): 1421–1428. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMC 6707464. PMID 31196864.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik M, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, Fullagar R, Wallis L, Smith M, et al. (July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (19 July 2017). "Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests". The New York Times.

- ^ Wood R (2 September 2017). "Comments on the chronology of Madjedbebe". Australian Archaeology. 83 (3): 172–174. doi:10.1080/03122417.2017.1408545. ISSN 0312-2417. S2CID 148777016.

- ^ O'Connell JF, Allen J, Williams MA, Williams AN, Turney CS, Spooner NA, et al. (August 2018). "Homo sapiens first reach Southeast Asia and Sahul?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (34): 8482–8490. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.8482O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808385115. PMC 6112744. PMID 30082377.

- ^ McChesney 2015.

- ^ Macaulay et al. (2005).

- ^ Posth et al. (2016).

See also "mtDNA from 55 hunter-gatherers across 35,000 years in Europe". Dienekes' Anthroplogy Blog. 8 February 2016. - ^ Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, Jay F, Sankararaman S, Sawyer S, et al. (January 2014) [Online 2013]. "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ Lachance J, Vernot B, Elbers CC, Ferwerda B, Froment A, Bodo JM, et al. (August 2012). "Evolutionary history and adaptation from high-coverage whole-genome sequences of diverse African hunter-gatherers". Cell. 150 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009. PMC 3426505. PMID 22840920.

- ^ Hammer MF, Woerner AE, Mendez FL, Watkins JC, Wall JD (September 2011). "Genetic evidence for archaic admixture in Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (37): 15123–15128. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10815123H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109300108. PMC 3174671. PMID 21896735.