| Reconstruction era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1865–1877 | |||

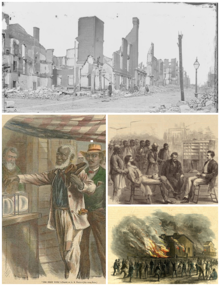

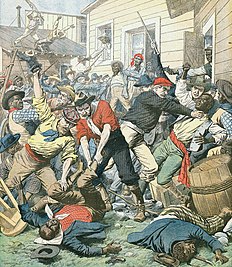

From left to right and top to the bottom: The ruins of Richmond, Virginia; newly-freed African Americans voting for the first time in 1867;[1] office of the Freedmen's Bureau in Memphis, Tennessee; Memphis riots of 1866 | |||

| Location | United States (Southern States) | ||

| Including | Third Party System | ||

| President(s) | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson Ulysses S. Grant Rutherford B. Hayes | ||

| Key events | Freedmen's Bureau Assassination of Abraham Lincoln Formation of the KKK Reconstruction Acts Impeachment of Andrew Johnson Enforcement Acts Reconstruction Amendments Compromise of 1877 | ||

Chronology

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

The Reconstruction era was a period in United States history and Southern United States history that followed the American Civil War and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the abolition of slavery and the reintegration of the eleven former Confederate States of America into the United States. During this period, three amendments were added to the United States Constitution to grant citizenship and equal civil rights to the newly freed slaves. To circumvent these legal achievements, the former Confederate states imposed poll taxes and literacy tests and engaged in terrorism to intimidate and control black people and to discourage or prevent them from voting.[2]

Throughout the war, the Union was confronted with the issue of how to administer areas it captured and how to handle the steady stream of slaves who were escaping to Union lines. In many cases, the United States Army played a vital role in establishing a free labor economy in the South, protecting freedmen's legal rights, and creating educational and religious institutions. Despite its reluctance to interfere with the institution of slavery, Congress passed the Confiscation Acts to seize Confederates' slaves, providing a precedent for president Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Congress later established a Freedmen's Bureau to provide much-needed food and shelter to the newly freed slaves.

As it became clear that the war would end in a Union victory, Congress debated the process for the readmission of the seceded states. Radical and moderate Republicans disagreed over the nature of secession, the conditions for readmission, and the desirability of social reforms as a consequence of the Confederate defeat. Lincoln favored the "ten percent plan" and vetoed the radical Wade–Davis Bill, which proposed strict conditions for readmission.

Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, just as fighting was drawing to a close. He was replaced by President Andrew Johnson. Johnson vetoed numerous Radical Republican bills, he pardoned thousands of Confederate leaders, and he allowed Southern states to pass draconian Black Codes that restricted the rights of freedmen. His actions outraged many Northerners and stoked fears that the Southern elite would regain its political power. Radical Republican candidates swept to power in the 1866 midterm elections, gaining large majorities in both houses of Congress.

In 1867 and 1868, the Radical Republicans passed the Reconstruction Acts over Johnson's vetoes, setting out the terms by which the former Confederate states could be readmitted to the Union. Constitutional conventions held throughout the South gave Black men the right to vote. New state governments were established by a coalition of freedmen, supportive white Southerners, and Northern transplants. They were opposed by "Redeemers," who sought to restore white supremacy and reestablish the Democratic Party's control of Southern governments and society. Violent groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and the Red Shirts, engaged in paramilitary insurgency and terrorism to disrupt the efforts of the Reconstruction governments and terrorize Republicans.[3] Congressional anger at President Johnson's repeated attempts to veto radical legislation led to his impeachment, but he was not removed from office.

Under Johnson's successor, President Ulysses S. Grant, Radical Republicans passed additional legislation to enforce civil rights, such as the Ku Klux Klan Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, continuing resistance to Reconstruction by Southern whites and its high cost contributed to its losing support in the North during the Grant administration. The 1876 presidential election was marked by widespread Black voter suppression in the South, and the result was close and contested. An Electoral Commission resulted in the Compromise of 1877, which awarded the election to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes on the understanding that federal troops would be withdrawn from the South, effectively bringing Reconstruction to an end. Post-Civil War efforts to enforce federal civil rights protections in the South ended in 1890 with the failure of the Lodge Bill.

Historians continue to disagree about the legacy of Reconstruction. Criticism of Reconstruction focuses on the early failure to prevent violence, corruption, starvation, disease, and other problems. Some consider the Union's policy toward freed slaves as inadequate and its policy toward former slaveholders as too lenient.[4] However, Reconstruction is credited with restoring the federal Union, limiting reprisals against the South, and establishing a legal framework for racial equality via the constitutional rights to national birthright citizenship, due process, equal protection of the laws, and male suffrage regardless of race.[5]

- ^ "The First Vote" by William Waud Archived February 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Harpers Weekly Nov. 16, 1867

- ^ "History & Culture - Reconstruction Era National Historical Park". U.S. National Park Service. www.nps.gov. February 24, 2023.

- ^ Rodrigue, John C. (2001). Reconstruction in the Cane Fields: From Slavery to Free Labor in Louisiana's Sugar Parishes, 1862–1880. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8071-5263-8.

- ^ Lynn, Samara; Thorbecke, Catherine (September 27, 2020). "What America owes: How reparations would look and who would pay". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Guelzo (2018), pp. 11–12; Foner (2019), p. 198.