| Reflex syncope | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Neurally mediated syncope, neurocardiogenic syncope[1][2] |

| |

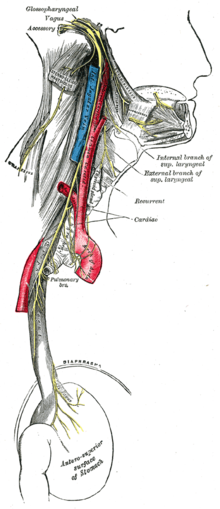

| Vagus nerve | |

| Specialty | Neurology, cardiovascular |

| Symptoms | Loss of consciousness before which there may be sweating, decreased ability to see, ringing in the ears[1][2] |

| Complications | Injury[1] |

| Duration | Brief[1] |

| Types | Vasovagal, situational, carotid sinus syncope[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, seizure, hypoglycemia[1] |

| Treatment | Avoiding triggers, drinking sufficient fluids, exercise, cardiac pacemaker[2] |

| Medication | Midodrine, fludrocortisone[4] |

| Frequency | > 1 per 1,000 people per year[1] |

Reflex syncope is a brief loss of consciousness due to a neurologically induced drop in blood pressure and/or a decrease in heart rate.[5][6][7][8][9][10][2] Before an affected person passes out, there may be sweating, a decreased ability to see, or ringing in the ears.[1] Occasionally, the person may twitch while unconscious.[1] Complications of reflex syncope include injury due to a fall.[1]

Reflex syncope is divided into three types: vasovagal, situational, and carotid sinus.[2] Vasovagal syncope is typically triggered by seeing blood, pain, emotional stress, or prolonged standing.[11] Situational syncope is often triggered by urination, swallowing, or coughing.[2] Carotid sinus syncope is due to pressure on the carotid sinus in the neck.[2] The underlying mechanism involves the nervous system slowing the heart rate and dilating blood vessels, resulting in low blood pressure and thus not enough blood flow to the brain.[2] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms after ruling out other possible causes.[3]

Recovery from a reflex syncope episode happens without specific treatment.[2] Prevention of episodes involves avoiding a person's triggers.[2] Drinking sufficient fluids, salt, and exercise may also be useful.[2][4] If this is insufficient for treating vasovagal syncope, medications such as midodrine or fludrocortisone may be tried.[4] Occasionally, a cardiac pacemaker may be used as treatment.[2] Reflex syncope affects at least 1 in 1,000 people per year.[1] It is the most common type of syncope, making up more than 50% of all cases.[2]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Aydin MA, Salukhe TV, Wilke I, Willems S (26 October 2010). "Management and therapy of vasovagal syncope: A review". World Journal of Cardiology. 2 (10): 308–15. doi:10.4330/wjc.v2.i10.308. PMC 2998831. PMID 21160608.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Adkisson WO, Benditt DG (September 2017). "Pathophysiology of reflex syncope: A review". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 28 (9): 1088–1097. doi:10.1111/jce.13266. PMID 28776824. S2CID 39638908.

- ^ a b Brignole M, Benditt DG (2011). Syncope: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 158. ISBN 9780857292018.

- ^ a b c Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, Cohen MI, Forman DE, Goldberger ZD, Grubb BP, Hamdan MH, Krahn AD, Link MS, Olshansky B, Raj SR, Sandhu RK, Sorajja D, Sun BC, Yancy CW (1 August 2017). "2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 136 (5): e25–e59. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498. PMID 28280232.

- ^ Morillo CA, Eckberg DL, Ellenbogen KA, Beightol LA, Hoag JB, Tahvanainen KU, Kuusela TA, Diedrich AM. Vagal and sympathetic mecha-nisms in patients with orthostatic vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 1997;96: 2509–2513. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2509

- ^ Abboud FM. Neurocardiogenic syncope. N Engl J Med. 1993: 1117–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281510

- ^ Chen-Scarabelli C, Scarabelli TM. Neurocardiogenic syncope. BMJ.2004;329:336–341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7461.336Abboud FM. Neuro-cardiogenic syncope. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1117–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281510

- ^ Grubb BP. Clinical practice. Neurocardiogenic syncope. N Engl J Med.2005;352:1004–1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042601

- ^ Barón-Esquivias G, Cayuela A, Gómez S, Aguilera A, Campos A, Fernández M, Cabezón S, Morán JE, Valle JI, Martínez A, et al. [Quality of life in patients with vasovagal syncope. Clinical parameters influence]. Med Clin (Barc). 2003;121:245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(03)75188-4

- ^ Zheng L, Sun W, Liu S, et al. The Diagnostic Value of Cardiac Deceleration Capacity in Vasovagal Syncope. Circ. Arrhythm. electrophysiol.. 2020;13(12):e008659. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008659, 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008659

- ^ "Syncope Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 9 November 2017.