Scandals of the Ulysses S. Grant administration | |

|---|---|

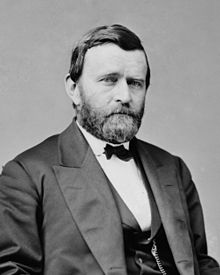

President Grant, c. 1870 | |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | General Grant National Memorial Manhattan, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 18th President of the United States Presidential campaigns

|

||

Ulysses S. Grant and his administration, including his cabinet, suffered many scandals, leading to a continuous reshuffling of officials. Grant, ever trusting of his chosen associates, had strong bonds of loyalty to those he considered friends. Grant was influenced by political forces of both reform and corruption. The standards in many of his appointments were low, and charges of corruption were widespread.[1] At times, however, Grant appointed various cabinet members who helped clean up the executive corruption. Starting with the Black Friday (1869) gold speculation ring, corruption would be discovered in seven federal departments. The Liberal Republicans, a political reform faction that bolted from the Republican Party in 1871, attempted to defeat Grant for a second term in office, but the effort failed. Taking over the House in 1875, the Democratic Party had more success in investigating, rooting out, and exposing corruption in the Grant Administration. Nepotism, although legally unrestricted at the time, was prevalent, with over 40 family members benefiting from government appointments and employment. In 1872, Senator Charles Sumner, labeled corruption in the Grant administration "Grantism."

The unprecedented way that Grant ran his cabinet, in a military-style rather than civilian, contributed to the scandals. For example, in 1869, Grant's private secretary Orville E. Babcock, rather than a State Department official, was sent to negotiate a treaty annexation with Santo Domingo. Grant never even consulted with cabinet members on the treaty annexation; in effect, the annexation proposal was already decided. A perplexed Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox reflected the cabinet's disappointment over not being consulted: "But Mr. President, has it been settled, then, that we want to Annex Santo Domingo?" Another instance of Grant's military-style command arose over the McGarrahan Claims, a legal dispute over mining patents in California, when Grant overrode the official opinion of Attorney General Ebenezer R. Hoar.[2] Both Cox and Hoar, who were reformers, eventually resigned from the cabinet in 1870.

Grant's reactions to the scandals ranged from prosecuting the perpetrators to protecting or pardoning those who were accused and convicted of the crimes. For example, when the Whiskey Ring scandal broke out in 1875, Grant, in a reforming mood, wrote: "Let no guilty man escape". However, when it was found out that Orville Babcock was indicted, Grant unprecedentedly testified against the government on behalf of the defendant. During his second term, Grant appointed reformers such as Benjamin Bristow, Edwards Pierrepont, and Zachariah Chandler who cleaned their respective departments of corruption. Grant finally dismissed Babcock, who was linked to several corruption charges and scandals, from the White House in 1876. It was with the encouragement of the reformers that Grant established the first Civil Service Commission, although other Republicans did not support him and the effort withered.[3][4] Grant's scandals have overshadowed his presidential achievements.[5]

- ^ Hinsdale (1911), pp.207, 212–213

- ^ Hinsdale 1911, pp.211–212

- ^ #McFeely-Woodward (1974), pp. 133–134

- ^ Cengage Advantage Books: Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People (2012), p. 593

- ^ "Daugherty (April 24, 2020)".