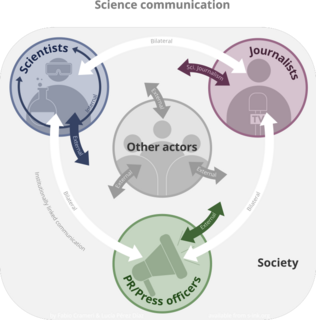

Science communication encompasses a wide range of activities that connect science and society.[1] Common goals of science communication include informing non-experts about scientific findings, raising the public awareness of and interest in science, influencing people's attitudes and behaviors, informing public policy, and engaging with diverse communities to address societal problems.[2] The term "science communication" generally refers to settings in which audiences are not experts on the scientific topic being discussed (outreach), though some authors categorize expert-to-expert communication ("inreach" such as publication in scientific journals) as a type of science communication.[3] Examples of outreach include science journalism[4][5] and health communication.[6] Since science has political, moral, and legal implications,[7] science communication can help bridge gaps between different stakeholders in public policy, industry, and civil society.[8]

| Part of a series on |

| Science |

|---|

| General |

| Branches |

| In society |

Science communicators are a broad group of people: scientific experts, science journalists, science artists, medical professionals, nature center educators, science advisors for policymakers, and everyone else who communicates with the public about science.[9][10] They often use entertainment and persuasion techniques including humour, storytelling, and metaphors to connect with their audience's values and interests.[11][12][13][14]

Science communication also exists as an interdisciplinary field of social science research[15][2] on topics such as misinformation,[16][17][18] public opinion of emerging technologies,[19][20][21] and the politicization and polarization of science.[22][23][24][25] For decades, science communication research has had only limited influence on science communication practice, and vice-versa,[8][26] but both communities are increasingly attempting to bridge research and practice.[27][28][29]

Historically, academic scientists were discouraged from spending time on public outreach, but that has begun to change. Research funders have raised their expectations for researchers to have broader impacts beyond publication in academic journals.[30] An increasing number of scientists, especially younger scholars, are expressing interest in engaging the public through social media and in-person events, though they still perceive significant institutional barriers to doing so.[31][32]

Science communication is closely related to the fields of informal science education, citizen science, and public engagement with science, and there is no general agreement on whether or how to distinguish them.[33][34][35][36] Like other aspects of society, science communication is influenced by systemic inequalities that impact both inreach[37][38][39][40][41] and outreach.[42][43][44][45][46]

- ^ Communicating science: a global perspective. Toss Gascoigne, Bernard Schiele, Joan Leach, Michelle Riedlinger, Bruce V. Lewenstein, Luisa Massarani, Peter Broks, Australian National University Press. Canberra, ACT, Australia. 2020. ISBN 978-1-76046-366-3. OCLC 1184001543.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Committee on the Science of Science Communication: a Research Agenda (2017). Communicating science effectively: a research agenda. Washington, DC. ISBN 978-0-309-45103-1. OCLC 975003235.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Illingworth, Sam; Allen, Grant (2020) [2016]. "Introduction". Effective science communication: a practical guide to surviving as a scientist (2nd ed.). Bristol, UK; Philadelphia: IOP Publishing. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1088/978-0-7503-2520-2ch1. ISBN 9780750325189. OCLC 1172776633.

This chapter provides a clearer distinction between the two aspects of science communication that are discussed in this book: that which is aimed at engaging scientists (inward-facing) and that which is aimed at engaging non-scientists (outward-facing).

- ^ Anderson, Josh; Dudo, Anthony (February 2023). "A View From the Trenches: Interviews With Journalists About Reporting Science News". Science Communication. 45 (1): 39–64. doi:10.1177/10755470221149156. ISSN 1075-5470. S2CID 256159505.

- ^ "How Science News does science journalism | Science News". 23 October 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Encouraging Adoption of Protective Behaviors to Mitigate the Spread of COVID-19: Strategies for Behavior Change. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 23 July 2020. doi:10.17226/25881. ISBN 978-0-309-68101-8. S2CID 241252994.

- ^ Scheufele, Dietram A. (16 September 2014). "Science communication as political communication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (supplement_4): 13585–13592. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317516111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4183176. PMID 25225389.

- ^ a b Jensen, Eric A.; Gerber, Alexander (2020). "Evidence-Based Science Communication". Frontiers in Communication. 4. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00078. ISSN 2297-900X.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Build Trust in Science for a Better Future". Association of Science Communicators. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "About". Association of Science Communicators. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

POIOlsonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Krulwichwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dudo, Anthony; Besley, John C. (16 April 2019). "What it means to 'know your audience' when communicating about science". The Conversation. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Dahlstrom, Michael F. (16 September 2014). "Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (supplement_4): 13614–13620. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320645111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4183170. PMID 25225368.

- ^ Guenther, Lars; Joubert, Marina (3 May 2017). "Science communication as a field of research: identifying trends, challenges and gaps by analysing research papers". Journal of Science Communication. 16 (2): A02. doi:10.22323/2.16020202. ISSN 1824-2049.

- ^ Ecker, Ullrich K. H.; Lewandowsky, Stephan; Cook, John; Schmid, Philipp; Fazio, Lisa K.; Brashier, Nadia; Kendeou, Panayiota; Vraga, Emily K.; Amazeen, Michelle A. (12 January 2022). "The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction". Nature Reviews Psychology. 1 (1): 13–29. doi:10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y. hdl:1983/889ddb0f-0d44-44f4-a54f-57c260ae4917. ISSN 2731-0574. S2CID 245916820.

- ^ Scheufele, Dietram A.; Krause, Nicole M. (16 April 2019). "Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (16): 7662–7669. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.7662S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1805871115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6475373. PMID 30642953.

- ^ Krause, Nicole M.; Freiling, Isabelle; Scheufele, Dietram A. (March 2022). "The "Infodemic" Infodemic: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of Truth-Claims and the Need for (Not) Combatting Misinformation". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 700 (1): 112–123. doi:10.1177/00027162221086263. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 248562334.

- ^ Scheufele, Dietram (2006). "Messages and Heuristics: How Audiences Form Attitudes About Emerging Technologies". In Turney, Jon (ed.). Engaging Science: Thoughts, Deeds, Analysis and Action. London: Wellcome Trust. pp. 20–25.

- ^ Anderson, Ashley A.; Brossard, Dominique; Scheufele, Dietram A.; Xenos, Michael A.; Ladwig, Peter (April 2014). "The "Nasty Effect:" Online Incivility and Risk Perceptions of Emerging Technologies: Crude comments and concern". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 19 (3): 373–387. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12009. S2CID 17198115.

- ^ Cacciatore, Michael A.; Anderson, Ashley A.; Choi, Doo-Hun; Brossard, Dominique; Scheufele, Dietram A.; Liang, Xuan; Ladwig, Peter J.; Xenos, Michael; Dudo, Anthony (September 2012). "Coverage of emerging technologies: A comparison between print and online media". New Media & Society. 14 (6): 1039–1059. doi:10.1177/1461444812439061. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 17445635.

- ^ Drummond, Caitlin; Fischhoff, Baruch (5 September 2017). "Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (36): 9587–9592. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9587D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704882114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5594657. PMID 28827344.

- ^ Motta, Matthew (October 2018). "The Polarizing Effect of the March for Science on Attitudes toward Scientists". PS: Political Science & Politics. 51 (4): 782–788. doi:10.1017/S1049096518000938. ISSN 1049-0965. S2CID 158825529.

- ^ Chinn, Sedona; Hart, P. Sol; Soroka, Stuart (February 2020). "Politicization and Polarization in Climate Change News Content, 1985-2017". Science Communication. 42 (1): 112–129. doi:10.1177/1075547019900290. ISSN 1075-5470. S2CID 212781410.

- ^ Hart, P. Sol; Chinn, Sedona; Soroka, Stuart (August 2020). "Politicization and Polarization in COVID-19 News Coverage". Science Communication. 42 (5): 679–697. doi:10.1177/1075547020950735. ISSN 1075-5470. PMC 7447862. PMID 38602988.

- ^ The first detailed empirical analysis of the international research field was commissioned by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research: Gerber, Alexander (2020). Science Communication Research: an Empirical Field Analysis. Germany: Edition innovare. ISBN 978-3-947540-02-0. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "about". SciCommBites. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Ropeik, David (14 March 2019). "Why Climate Change Pundits Aren't Convincing Anyone". Undark. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (9 April 2023). "Standing Committee on Advancing Science Communication". National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Broader Impacts". NSF - National Science Foundation. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Rose, Kathleen M.; Markowitz, Ezra M.; Brossard, Dominique (21 January 2020). "Scientists' incentives and attitudes toward public communication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (3): 1274–1276. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.1274R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1916740117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6985784. PMID 31911470.

- ^ Calice, Mikhaila N.; Beets, Becca; Bao, Luye; Scheufele, Dietram A.; Freiling, Isabelle; Brossard, Dominique; Feinstein, Noah Weeth; Heisler, Laura; Tangen, Travis; Handelsman, Jo (15 June 2022). Baert, Stijn (ed.). "Public engagement: Faculty lived experiences and perspectives underscore barriers and a changing culture in academia". PLOS ONE. 17 (6): e0269949. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1769949C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269949. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9200360. PMID 35704652.

- ^ Ellenbogen, Kirsten (January 2013). "The Convergence of Informal Science Education and Science Communication". Curator: The Museum Journal. 56 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1111/cura.12002.

- ^ "Communicating the Future: Engaging the Public in Basic Science". SciPEP. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Vohland, Katrin; Land-Zandstra, Anne; Ceccaroni, Luigi; Lemmens, Rob; Perelló, Josep; Ponti, Marisa; Samson, Roeland; Wagenknecht, Katherin, eds. (2021). The Science of Citizen Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4. ISBN 978-3-030-58277-7. S2CID 234242494.

- ^ Martin, Victoria Y. (April 2017). "Citizen Science as a Means for Increasing Public Engagement in Science: Presumption or Possibility?". Science Communication. 39 (2): 142–168. doi:10.1177/1075547017696165. ISSN 1075-5470. S2CID 149690668.

- ^ Bjork, Collin (2022). "Book Review: H. Glasman-Deal, Science Research Writing for Native and Non-Native Speakers of English". Journal of Second Language Writing. 56. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2022.100877. S2CID 247394793.

- ^ Smith, Olivia M.; Davis, Kayla L.; Pizza, Riley B.; Waterman, Robin; Dobson, Kara C.; Foster, Brianna; Jarvey, Julie C.; Jones, Leonard N.; Leuenberger, Wendy; Nourn, Nan; Conway, Emily E.; Fiser, Cynthia M.; Hansen, Zoe A.; Hristova, Ani; Mack, Caitlin (13 March 2023). "Peer review perpetuates barriers for historically excluded groups". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 7 (4): 512–523. Bibcode:2023NatEE...7..512S. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-01999-w. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 36914773. S2CID 257506860.

- ^ Freelon, Deen; Pruden, Meredith L; Eddy, Kirsten A; Kuo, Rachel (17 February 2023). "Inequities of race, place, and gender among the communication citation elite, 2000–2019". Journal of Communication. 73 (4): 356–367. doi:10.1093/joc/jqad002. ISSN 0021-9916.

- ^ Zheng, Xiang; Yuan, Haimiao; Ni, Chaoqun (13 July 2022). Groll, Helga; Rodgers, Peter (eds.). "How parenthood contributes to gender gaps in academia". eLife. 11: e78909. doi:10.7554/eLife.78909. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 9299837. PMID 35822694.

- ^ Ni, Chaoqun; Smith, Elise; Yuan, Haimiao; Larivière, Vincent; Sugimoto, Cassidy R. (3 September 2021). "The gendered nature of authorship". Science Advances. 7 (36): eabe4639. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.4639N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe4639. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 8442765. PMID 34516891.

- ^ Lewenstein, Bruce V. (2022). "Is Citizen Science a Remedy for Inequality?". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 700: 183–194. doi:10.1177/00027162221092697. S2CID 248562327.

- ^ Amarasekara, Inoka; Grant, Will J (January 2019). "Exploring the YouTube science communication gender gap: A sentiment analysis". Public Understanding of Science. 28 (1): 68–84. doi:10.1177/0963662518786654. ISSN 0963-6625. PMID 29974815. S2CID 49692053.

- ^ Hu, Jane C. (14 February 2017). "Gender Differences in Pitching: Results from the TON Pitching Habits Survey". The Open Notebook. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Santos-Muñiz, Mariela (10 December 2019). "On the Shortage of Spanish-Language Science Journalism in U.S. Media". The Open Notebook. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "Anti-racist science communication starts with recognising its globally diverse historical footprint". Impact of Social Sciences. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2023.