| Epileptic seizure | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Epileptic fit,[1] seizure, fit, convulsions[2] |

| |

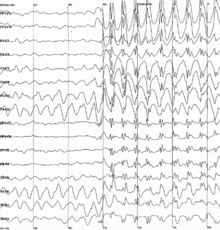

| Generalized 3 Hz spike and wave discharges in an electroencephalogram (EEG) of a patient with epilepsy | |

| Specialty | Neurology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Variable[3] |

| Complications | Falling, drowning, car accidents, pregnancy complications, emotional health issues[4] |

| Duration | Typically < 2 minutes[5] |

| Types | Focal, generalized; Provoked, unprovoked[6] |

| Causes | Provoked: Low blood sugar, alcohol withdrawal, low blood sodium, fever, brain infection, traumatic brain injury[3][6] Unprovoked: Flashing Lights/Colors Unknown, brain injury, brain tumor, previous stroke[6][7][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, blood tests, medical imaging, electroencephalography[7] |

| Differential diagnosis | Syncope, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure, migraine aura, transient ischemic attack[3][8] |

| Treatment | Less than 5 min: Place person on their side, remove nearby dangerous objects More than 5 min: Treat as per status epilepticus[3][5][9] |

| Frequency | ~10% of people (overall worldwide lifetime risk)[10][11] |

A seizure is a sudden change in behavior, movement, and/or consciousness due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain.[3][6] Seizures can look different in different people. It can be uncontrolled shaking of the whole body (tonic-clonic seizures) or a person spacing out for a few seconds (absence seizures).[3][12][8] Most seizures last less than two minutes.[5] They are then followed by confusion/drowsiness before the person returns to normal.[3][8] If a seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes, it is a medical emergency (status epilepticus) and needs immediate treatment.[3][5][13]

Seizures can be classified as provoked or unprovoked.[3][6] Provoked seizures have a cause that can be fixed, such as low blood sugar, alcohol withdrawal, high fever, recent stroke, and recent head trauma.[3][6] Unprovoked seizures have no clear cause or fixable cause.[3][6][7] Examples include past strokes, brain tumors, brain vessel malformations, and genetic disorders.[3] Sometimes, no cause is found, and this is called idiopathic.[5][14] After a first unprovoked seizure, the chance of experiencing a second one is about 40% within 2 years.[5][15] People with repeated unprovoked seizures are diagnosed with epilepsy.[5][6]

Doctors assess a seizure by first ruling out other conditions that look similar to seizures, such as fainting and strokes.[3][8] This includes taking a detailed history and ordering blood tests.[3][14] They may also order an electroencephalogram (EEG) and brain imaging (CT and/or MRI).[3][7] If this is a person's first seizure and it's provoked, treatment of the cause is usually enough to treat the seizure.[3] If the seizure is unprovoked, brain imaging is abnormal, and/or EEG is abnormal, it is recommended to start anti-seizure medications.[3][7][15]

- ^ Shorvon S (2009). Epilepsy. OUP Oxford. p. 1. ISBN 9780199560042.

- ^ "Epileptic Seizures - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Berkowitz, Aaron L. (2022). "Seizures & Epilepsy". Clinical Neurology & Neuroanatomy: A Localization-Based Approach (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1260453362.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Seizures – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abou-Khalil, Bassel W.; Gallagher, Martin J.; Macdonald, Robert L. (2022). "Epilepsies". Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice (8th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1614–1663. ISBN 978-0323642613.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. (April 2014). "ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 55 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1111/epi.12550. PMID 24730690. S2CID 35958237.

- ^ a b c d e Wilden JA, Cohen-Gadol AA (August 2012). "Evaluation of first nonfebrile seizures". American Family Physician. 86 (4): 334–340. PMID 22963022.

- ^ a b c d Winkel, Daniel; Cassimatis, Dimitri (2022). "Episodic Impairment of Consciousness". Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice (8th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 8–16. ISBN 978-0323642613.

- ^ Cruickshank, Moira; Imamura, Mari; Booth, Corinne; Aucott, Lorna; Counsell, Carl; Manson, Paul; Scotland, Graham; Brazzelli, Miriam (2022). "Pre-hospital and emergency department treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in adults: an evidence synthesis". Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 26 (20): 1–76. doi:10.3310/RSVK2062. ISSN 2046-4924. PMC 8977974. PMID 35333156.

- ^ Ferri FF (2018). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2019 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 959. ISBN 9780323550765.

- ^ "Epilepsy". World Health Organization. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Misulis KE, Murray EL (2017). Essentials of Hospital Neurology. Oxford University Press. p. Chapter 19. ISBN 9780190259433.

- ^ Cruickshank, Moira; Imamura, Mari; Booth, Corinne; Aucott, Lorna; Counsell, Carl; Manson, Paul; Scotland, Graham; Brazzelli, Miriam (2022). "Pre-hospital and emergency department treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in adults: an evidence synthesis". Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 26 (20): 1–76. doi:10.3310/RSVK2062. ISSN 2046-4924. PMC 8977974. PMID 35333156.

- ^ a b Ropper, Allan H.; Samuels, Martin A.; Klein, Joshua P.; PrasadPrasad, Sashank (2023). "Epilepsy and Other Seizure Disorders". Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1264264520.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page).