| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 5-HT, 5-Hydroxytryptamine, Enteramine, Thrombocytin, 3-(β-Aminoethyl)-5-hydroxyl solution , Thrombotonin |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | raphe nuclei, enterochromaffin cells |

| Target tissues | system-wide |

| Receptors | 5-HT1, 5-HT2, 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 |

| Agonists | Indirectly: SSRIs, MAOIs |

| Precursor | 5-HTP |

| Biosynthesis | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase |

| Metabolism | MAO |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.054 |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

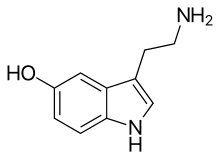

| IUPAC name

5-Hydroxytryptamine

| |

| Preferred IUPAC name

3-(2-Aminoethyl)-1H-indol-5-ol | |

| Other names

5-Hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT, Enteramine; Thrombocytin, 3-(β-Aminoethyl)-5-hydroxyindole, 3-(2-Aminoethyl)indol-5-ol, Thrombotonin

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.054 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Serotonin |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H12N2O | |

| Molar mass | 176.215 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Melting point | 167.7 °C (333.9 °F; 440.8 K) 121–122 °C (ligroin)[3] |

| Boiling point | 416 ± 30 °C (at 760 Torr)[1] |

| slightly soluble | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.16 in water at 23.5 °C[2] |

| 2.98 D | |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

750 mg/kg (subcutaneous, rat),[4] 4500 mg/kg (intraperitoneal, rat),[5] 60 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Serotonin (/ˌsɛrəˈtoʊnɪn, ˌsɪərə-/)[6][7][8] or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is a monoamine neurotransmitter. Its biological function is complex, touching on diverse functions including mood, cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes such as vomiting and vasoconstriction.[9]

Serotonin is produced in the central nervous system (CNS), specifically in the brainstem's raphe nuclei, the skin's Merkel cells, pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and the tongue's taste receptor cells. Approximately 90% of the serotonin the human body produces is in the gastrointestinal tract's enterochromaffin cells, where it regulates intestinal movements.[10][11][12] Additionally, it is stored in blood platelets and is released during agitation and vasoconstriction, where it then acts as an agonist to other platelets.[13] About 8% is found in platelets and 1–2% in the CNS.[14]

The serotonin is secreted luminally and basolaterally, which leads to increased serotonin uptake by circulating platelets and activation after stimulation, which gives increased stimulation of myenteric neurons and gastrointestinal motility.[15] The remainder is synthesized in serotonergic neurons of the CNS, where it has various functions, including the regulation of mood, appetite, and sleep.[16][unreliable medical source][17][unreliable medical source]

Serotonin secreted from the enterochromaffin cells eventually finds its way out of tissues into the blood. There, it is actively taken up by blood platelets, which store it. When the platelets bind to a clot, they release serotonin, where it can serve as a vasoconstrictor or a vasodilator while regulating hemostasis and blood clotting. In high concentrations, serotonin acts as a vasoconstrictor by contracting endothelial smooth muscle directly or by potentiating the effects of other vasoconstrictors (e.g. angiotensin II and norepinephrine). The vasoconstrictive property is mostly seen in pathologic states affecting the endothelium – such as atherosclerosis or chronic hypertension. In normal physiologic states, vasodilation occurs through the serotonin mediated release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells, and the inhibition of release of norepinephrine from adrenergic nerves.[18] Serotonin is also a growth factor for some types of cells, which may give it a role in wound healing. There are various serotonin receptors.

Biochemically, the indoleamine molecule derives from the amino acid tryptophan. Serotonin is metabolized mainly to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), chiefly by the liver.

Several classes of antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), interfere with the normal reabsorption of serotonin after it is done with the transmission of the signal, therefore augmenting the neurotransmitter levels in the synapses.

Besides mammals, serotonin is found in all bilateral animals including worms and insects,[19] as well as in fungi and in plants.[20] Serotonin's presence in insect venoms and plant spines serves to cause pain, which is a side-effect of serotonin injection.[21][22] Serotonin is produced by pathogenic amoebae, causing diarrhea in the human gut.[23] Its widespread presence in many seeds and fruits may serve to stimulate the digestive tract into expelling the seeds.[24][failed verification]

- ^ Calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V11.02 (©1994–2011 ACD/Labs)

- ^ Mazák K, Dóczy V, Kökösi J, Noszál B (April 2009). "Proton speciation and microspeciation of serotonin and 5-hydroxytryptophan". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 6 (4): 578–590. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200800087. PMID 19353542. S2CID 20543931.

- ^ Pietra S (1958). "[Indolic derivatives. II. A new way to synthesize serotonin]". Il Farmaco; Edizione Scientifica (in Italian). 13 (1): 75–79. PMID 13524273.

- ^ Erspamer V (1952). "Ricerche preliminari sulle indolalchilamine e sulle fenilalchilamine degli estratti di pelle di Anfibio". Ricerca Scientifica. 22: 694–702.

- ^ Tammisto T (1967). "Increased toxicity of 5-hydroxytryptamine by ethanol in rats and mice". Annales Medicinae Experimentalis et Biologiae Fenniae. 46 (3): 382–384. PMID 5734241.

- ^ Jones D (2003) [1917]. Roach P, Hartmann J, Setter J (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ^ "Serotonin". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Serotonin". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Young SN (November 2007). "How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 32 (6): 394–399. PMC 2077351. PMID 18043762.

- ^ "Microbes Help Produce Serotonin in Gut". California Institute of Technology. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ King MW. "Serotonin". The Medical Biochemistry Page. Indiana University School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL (2009). "The expanded biology of serotonin". Annual Review of Medicine. 60: 355–366. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. PMC 5864293. PMID 19630576.

- ^ Schlienger RG, Meier CR (2003). "Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet activation: can they prevent acute myocardial infarction?". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 3 (3): 149–162. doi:10.2165/00129784-200303030-00001. PMID 14727927. S2CID 23986530.

- ^ Kling A (2013). 5-HT2A: a serotonin receptor with a possible role in joint diseases (PDF) (Thesis). Umeå Universitet. ISBN 978-91-7459-549-9.

- ^ Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, et al. (April 2015). "Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis". Cell. 161 (2): 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. PMC 4393509. PMID 25860609.

- ^ Sangare A, Dubourget R, Geoffroy H, Gallopin T, Rancillac A (October 2016). "Serotonin differentially modulates excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to putative sleep-promoting neurons of the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus" (PDF). Neuropharmacology. 109: 29–40. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.015. PMID 27238836.

- ^ Rancillac A (November 2016). "Serotonin and sleep-promoting neurons". Oncotarget. 7 (48): 78222–78223. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13419. PMC 5346632. PMID 27861160.

- ^ Vanhoutte PM (February 1987). "Serotonin and the vascular wall". International Journal of Cardiology. 14 (2): 189–203. doi:10.1016/0167-5273(87)90008-8. PMID 3818135.

- ^ Huser A, Rohwedder A, Apostolopoulou AA, Widmann A, Pfitzenmaier JE, Maiolo EM, et al. (2012). Zars T (ed.). "The serotonergic central nervous system of the Drosophila larva: anatomy and behavioral function". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e47518. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747518H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047518. PMC 3474743. PMID 23082175.

- ^ Ramakrishna A, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA (June 2011). "Phytoserotonin: a review". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 6 (6): 800–809. Bibcode:2011PlSiB...6..800A. doi:10.4161/psb.6.6.15242. PMC 3218476. PMID 21617371.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chen_2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Erspamer V (1966). "Occurrence of indolealkylamines in nature". 5-Hydroxytryptamine and Related Indolealkylamines. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 132–181. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-85467-5_4. ISBN 978-3-642-85469-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid6308760was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

feldwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).