Sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Rome are indicated by art, literature, and inscriptions, and to a lesser extent by archaeological remains such as erotic artifacts and architecture. It has sometimes been assumed that "unlimited sexual license" was characteristic of ancient Rome,[1][2] but sexuality was not excluded as a concern of the mos maiorum, the traditional social norms that affected public, private, and military life.[3] Pudor, "shame, modesty", was a regulating factor in behavior,[4] as were legal strictures on certain sexual transgressions in both the Republican and Imperial periods.[5] The censors—public officials who determined the social rank of individuals—had the power to remove citizens from the senatorial or equestrian order for sexual misconduct, and on occasion did so.[6][7] The mid-20th-century sexuality theorist Michel Foucault regarded sex throughout the Greco-Roman world as governed by restraint and the art of managing sexual pleasure.[8]

Roman society was patriarchal (see paterfamilias), and masculinity was premised on a capacity for governing oneself and others of lower status, not only in war and politics, but also in sexual relations.[9] Virtus, "virtue", was an active masculine ideal of self-discipline, related to the Latin word for "man", vir. The corresponding ideal for a woman was pudicitia, often translated as chastity or modesty, but a more positive and even competitive personal quality that displayed both her attractiveness and self-control.[10] Roman women of the upper classes were expected to be well educated, strong of character, and active in maintaining their family's standing in society.[11] With extremely few exceptions, surviving Latin literature preserves the voices of educated male Romans on sexuality. Visual art was created by those of lower social status and of a greater range of ethnicity, but was tailored to the taste and inclinations of those wealthy enough to afford it, including, in the Imperial era, former slaves.[12]

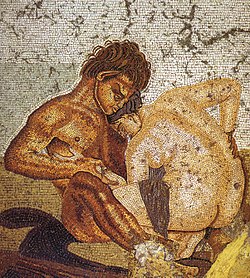

Some sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Roman culture differ markedly from those in later Western societies.[13][14] Roman religion promoted sexuality as an aspect of prosperity for the state, and individuals might turn to private religious practice or "magic" for improving their erotic lives or reproductive health. Prostitution was legal, public, and widespread.[15] "Pornographic" paintings were featured among the art collections in respectable upperclass households.[16] It was considered natural and unremarkable for men to be sexually attracted to teen-aged youths of both sexes, and even pederasty was condoned as long as the younger male partner was not a freeborn Roman. "Homosexual" and "heterosexual" did not form the primary dichotomy of Roman thinking about sexuality, and no Latin words for these concepts exist.[17] No moral censure was directed at the man who enjoyed sex acts with either women or males of inferior status, as long as his behaviors revealed no weaknesses or excesses, nor infringed on the rights and prerogatives of his masculine peers. While perceived effeminacy was denounced, especially in political rhetoric, sex in moderation with male prostitutes or slaves was not regarded as improper or vitiating to masculinity, if the male citizen took the active and not the receptive role. Hypersexuality, however, was condemned morally and medically in both men and women. Women were held to a stricter moral code,[18] and same-sex relations between women are poorly documented, but the sexuality of women is variously celebrated or reviled throughout Latin literature. In general the Romans had more fluid gender boundaries than the ancient Greeks.[19]

A late-20th-century paradigm analyzed Roman sexuality in relation to a "penetrator–penetrated" binary model. This model, however, has limitations, especially in regard to expressions of sexuality among individual Romans.[20] Even the relevance of the word "sexuality" to ancient Roman culture has been disputed;[21][22][23] but in the absence of any other label for "the cultural interpretation of erotic experience", the term continues to be used.[24]

- ^ Edwards, p. 65.

- ^ "The sexuality of the Romans has never had good press in the West ever since the rise of Christianity. In the popular imagination and culture, it is synonymous with sexual license and abuse": Beert C. Verstraete and Provencal, Vernon, eds., Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition (Haworth Press, 2005), p. 5. For an extended discussion of how the modern perception of Roman sexual decadence can be traced to early Christian polemic, see Alastair J. L. Blanshard, "Roman Vice," in Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), pp. 1–88.

- ^ Karl-J. Hölkeskamp, Reconstructing the Roman Republic: An Ancient Political Culture and Modern Research (Princeton University Press, 2010), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Langlands, p. 17.

- ^ Langlands, p. 20.

- ^ Fantham, p. 121

- ^ Richlin (1993), p. 556. Under the Empire, the emperor assumed the powers of the censors (p. 560).

- ^ Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: The Care of the Self (New York: Vintage Books, 1988), vol. 3, p. 239 (on the contrast with the Christian view of sex as "linked to evil") et passim, as summarized by Inger Furseth and Pål Repstad, An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion: Classical and Contemporary Perspectives (Ashgate, 2006), p. 64.

- ^ Cantarella, p. xii.

- ^ Langlands, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Cantarella, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ Clarke, pp. 9, 153ff.

- ^ Langlands, p. 31, especially note 55

- ^ Clarke, p. 11.

- ^ Strong, Anise K. (2016). "Prostitutes and matrons in the urban landscape". Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 142–170. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316563083.007. ISBN 9781316563083.

- ^ McGinn (2004), p. 164.

- ^ Williams, p. 304, citing Saara Lilja, Homosexuality in Republican and Augustan Rome (Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 1983), p. 122.

- ^ Nussbaum, pp. 299–300

- ^ Hallett, p. 11.

- ^ Langlands, p. 13.

- ^ Clarke, p. 8, maintains that the ancient Romans "did not have a self-conscious idea of their sexuality".

- ^ Penner, pp. 15–16

- ^ Habinek, pp. 2ff.

- ^ Edwards, pp. 66–67, especially note 12.