| Shroud of Turin | |

|---|---|

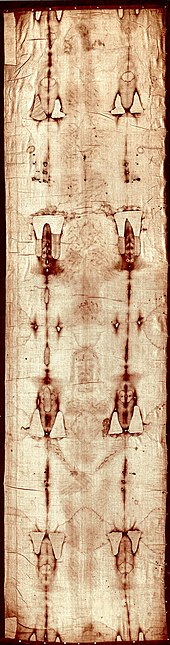

The Shroud of Turin: modern photo of the face, positive (left), and digitally processed image (right) | |

| Material | Linen |

| Size | 4.4 m × 1.1 m (14 ft 5 in × 3 ft 7 in) |

| Present location | Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Turin, Italy |

| Period | 13th to 14th century[1] |

The Shroud of Turin (Italian: Sindone di Torino), also known as the Holy Shroud[2][3] (Italian: Sacra Sindone), is a length of linen cloth that bears a faint image of the front and back of a man. It has been venerated for centuries, especially by members of the Catholic Church, as the actual burial shroud used to wrap the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his crucifixion, and upon which Jesus's bodily image is miraculously imprinted. The human image on the shroud can be discerned more clearly in a black and white photographic negative than in its natural sepia color, an effect discovered in 1898 by Secondo Pia, who produced the first photographs of the shroud. This negative image is associated with a popular Catholic devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus.

The documented history of the shroud dates back to 1354, when it was exhibited in the new collegiate church of Lirey, a village in north-central France.[4]: 80–81 The shroud was denounced as a forgery by the bishop of Troyes, Pierre d’Arcis, in 1389.[4]: 90–96 It was acquired by the House of Savoy in 1453 and later deposited in a chapel in Chambéry,[4]: 141–142, 153–154 where it was damaged by fire in 1532.[4]: 166 In 1578, the Savoys moved the shroud to their new capital in Turin, where it has remained ever since.[4]: 191 Since 1683, it has been kept in the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, which was designed for that purpose by architect Guarino Guarini and which is connected to both the royal palace and the Turin Cathedral.[4]: 233 Ownership of the shroud passed from the House of Savoy to the Catholic Church after the death of former king Umberto II in 1983.[4]: 415

The microscopist Walter McCrone found, based on his examination of samples taken in 1978 from the surface of the shroud using adhesive tape, that the image on the shroud had been painted with a dilute solution of red ochre pigment in a gelatin medium. McCrone found that the apparent bloodstains were painted with vermilion pigment, also in a gelatin medium.[5] McCrone's findings were disputed by other researchers and the nature of the image on the shroud continues to be debated.[4]: 364–366

Radiocarbon dating has established that the shroud is from the medieval period, and not from the time of Jesus.[6] This corresponds with its first documented appearance in 1354. Defenders of the authenticity of the shroud have questioned this finding, usually on the basis that the samples tested might have been contaminated or taken from a repair to the original fabric. Such fringe theories have been refuted by carbon-dating experts and others based on evidence from the shroud itself.[7] Refuted theories include the medieval repair theory,[8][9][10] the bio-contamination theories[11] and the carbon monoxide theory.[12][13] Though accepted as valid by experts, the carbon-dating of the shroud continues to generate significant public debate.[14][15][4]: 424–445

The nature and history of the shroud have been the subjects of extensive and long-lasting controversies in both the scholarly literature and the popular press.[16][17][18][19][20] Currently, the Catholic Church neither endorses nor rejects the authenticity of the shroud as a relic of Jesus.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Radiocarbon Dating, Second Editionwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Britannicawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

29DLvwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i Cite error: The named reference

Nicolottiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

McCrone-90was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

taylorwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Radiocarbon Dating pg 167-168was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

R.A. Freer-Waters, A.J.T. Jull 2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

freeinquiry1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

jAsd9was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gove 1990was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

c14.arch.ox.ac.ukwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

chemistryworldwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Why Shroud of Turin's Secrets Continue to Elude Science". History. 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Moorhead, Joanna (17 April 2022). "The $1m challenge: 'If the Turin Shroud is a forgery, show how it was done'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

kJeDswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Meacham 1983was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

GVf9Kwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

oattpwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

kl2Oqwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).