| Sleep apnea | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sleep apnoea, sleep apnea syndrome |

| |

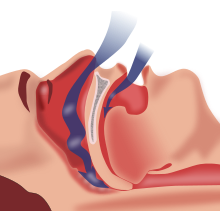

| Obstructive sleep apnea: At bottom-center, nasopharyngeal tissue falls to the back of the throat when in a supine posture, occluding normal breath and causing various complications. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Pauses breathing or periods of shallow breathing during sleep, snoring, tired during the day[1][2] |

| Complications | Heart attack, Cardiac arrest, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, irregular heartbeat, obesity, motor vehicle collisions,[1] Alzheimer's disease,[3] and premature death[4] |

| Usual onset | Varies; up to 50% of women age 20–70[5] |

| Types | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), central sleep apnea (CSA), mixed sleep apnea[1] |

| Risk factors | Overweight, family history, allergies, enlarged tonsils,[6] asthma[7] |

| Diagnostic method | Overnight sleep study[8] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~ 1 in every 10 people,[3][9] 2:1 ratio of men to women, aging and obesity higher risk[5] |

Sleep apnea (sleep apnoea or sleep apnœa in British English) is a sleep-related breathing disorder in which repetitive pauses in breathing, periods of shallow breathing, or collapse of the upper airway during sleep results in poor ventilation and sleep disruption.[10][11] Each pause in breathing can last for a few seconds to a few minutes and occurs many times a night.[1] A choking or snorting sound may occur as breathing resumes.[1] Common symptoms include daytime sleepiness, snoring, and non restorative sleep despite adequate sleep time.[12] Because the disorder disrupts normal sleep, those affected may experience sleepiness or feel tired during the day.[1] It is often a chronic condition.[13]

Sleep apnea may be categorized as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), in which breathing is interrupted by a blockage of air flow, central sleep apnea (CSA), in which regular unconscious breath simply stops, or a combination of the two.[1] OSA is the most common form.[1] OSA has four key contributors; these include a narrow, crowded, or collapsible upper airway, an ineffective pharyngeal dilator muscle function during sleep, airway narrowing during sleep, and unstable control of breathing (high loop gain).[14][15] In CSA, the basic neurological controls for breathing rate malfunction and fail to give the signal to inhale, causing the individual to miss one or more cycles of breathing. If the pause in breathing is long enough, the percentage of oxygen in the circulation can drop to a lower than normal level (hypoxaemia) and the concentration of carbon dioxide can build to a higher than normal level (hypercapnia).[16] In turn, these conditions of hypoxia and hypercapnia will trigger additional effects on the body such as Cheyne-Stokes Respiration.[17]

Some people with sleep apnea are unaware they have the condition.[1] In many cases it is first observed by a family member.[1] An in-lab sleep study overnight is the preferred method for diagnosing sleep apnea.[15] In the case of OSA, the outcome that determines disease severity and guides the treatment plan is the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).[15] This measurement is calculated from totaling all pauses in breathing and periods of shallow breathing lasting greater than 10 seconds and dividing the sum by total hours of recorded sleep.[10][15] In contrast, for CSA the degree of respiratory effort, measured by esophageal pressure or displacement of the thoracic or abdominal cavity, is an important distinguishing factor between OSA and CSA.[18]

A systemic disorder, sleep apnea is associated with a wide array of effects, including increased risk of car accidents, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, atrial fibrillation, insulin resistance, higher incidence of cancer, and neurodegeneration.[19] Further research is being conducted on the potential of using biomarkers to understand which chronic diseases are associated with sleep apnea on an individual basis.[19]

Treatment may include lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, and surgery.[1] Effective lifestyle changes may include avoiding alcohol, losing weight, smoking cessation, and sleeping on one's side.[20] Breathing devices include the use of a CPAP machine.[21] With proper use, CPAP improves outcomes.[22] Evidence suggests that CPAP may improve sensitivity to insulin, blood pressure, and sleepiness.[23][24][25] Long term compliance, however, is an issue with more than half of people not appropriately using the device.[22][26] In 2017, only 15% of potential patients in developed countries used CPAP machines, while in developing countries well under 1% of potential patients used CPAP.[27] Without treatment, sleep apnea may increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, heart failure, irregular heartbeat, obesity, and motor vehicle collisions.[1]

OSA is a common sleep disorder. A large analysis in 2019 of the estimated prevalence of OSA found that OSA affects 936 million—1 billion people between the ages of 30–69 globally, or roughly every 1 in 10 people, and up to 30% of the elderly.[28] Sleep apnea is somewhat more common in men than women, roughly a 2:1 ratio of men to women, and in general more people are likely to have it with older age and obesity. Other risk factors include being overweight,[19] a family history of the condition, allergies, and enlarged tonsils.[6]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Sleep Apnea: What Is Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI: Health Information for the Public. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Jackson et al 2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Austin D, Nieto FJ, Stubbs R, Hla KM (1 August 2008). "Sleep Disordered Breathing and Mortality: Eighteen-Year Follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort". Sleep. 31 (8): 1071–1078. PMC 2542952. PMID 18714778. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b Franklin KA, Lindberg E (2015). "Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (8): 1311–1322. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. PMC 4561280. PMID 26380759.

- ^ a b "Who Is at Risk for Sleep Apnea?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Dixit, Ramakant (2018). "Asthma and obstructive sleep apnea: More than an association!". Lung India. 35 (3): 191–192. doi:10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_241_17. PMC 5946549. PMID 29697073.

- ^ "How Is Sleep Apnea Diagnosed?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Owen et al 2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Chang JL, Goldberg AN, Alt JA, Mohammed A, Ashbrook L, Auckley D, Ayappa I, Bakhtiar H, Barrera JE, Bartley BL, Billings ME, Boon MS, Bosschieter P, Braverman I, Brodie K (13 July 2023). "International Consensus Statement on Obstructive Sleep Apnea". International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 13 (7): 1061–1482. doi:10.1002/alr.23079. ISSN 2042-6976. PMC 10359192. PMID 36068685.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Roberts-2022was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stansbury RC, Strollo PJ (7 September 2015). "Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (9): E298-310. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.13. ISSN 2077-6624. PMC 4598518. PMID 26543619. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Punjabi NM (15 February 2008). "The Epidemiology of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 5 (2): 136–143. doi:10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. ISSN 1546-3222. PMC 2645248. PMID 18250205.

- ^ Dolgin E (29 April 2020). "Treating sleep apnea with pills instead of machines". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-042820-1. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Osman AM, Carter SG, Carberry JC, Eckert DJ (2018). "Obstructive sleep apnea: Current perspectives". Nature and Science of Sleep. 10: 21–34. doi:10.2147/NSS.S124657. PMC 5789079. PMID 29416383.

- ^ Majmundar SH, Patel S (27 October 2018). Physiology, Carbon Dioxide Retention. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494063. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Rudrappa M, Modi P, Bollu P (1 August 2022). Cheyne Stokes Respirations. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846350. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023.

- ^ Badr MS, Javaheri S (March 2019). "Central Sleep Apnea: a Brief Review". Current Pulmonology Reports. 8 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1007/s13665-019-0221-z. ISSN 2199-2428. PMC 6883649. PMID 31788413.

- ^ a b c Lim DC, Pack AI (14 January 2017). "Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Update and Future". Annual Review of Medicine. 68 (1): 99–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-042915-102623. ISSN 0066-4219. PMID 27732789. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM (14 April 2020). "Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review". JAMA. 323 (14): 1389–1400. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3514. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 32286648. S2CID 215759986. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?". NHLBI. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b Spicuzza L, Caruso D, Di Maria G (September 2015). "Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and its management". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 6 (5): 273–85. doi:10.1177/2040622315590318. PMC 4549693. PMID 26336596.

- ^ Iftikhar IH, Khan MF, Das A, Magalang UJ (April 2013). "Meta-analysis: continuous positive airway pressure improves insulin resistance in patients with sleep apnea without diabetes". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 10 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201209-081oc. PMC 3960898. PMID 23607839.

- ^ Haentjens P, Van Meerhaeghe A, Moscariello A, De Weerdt S, Poppe K, Dupont A, Velkeniers B (April 2007). "The impact of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: evidence from a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials". Archives of Internal Medicine. 167 (8): 757–64. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.8.757. PMID 17452537.

- ^ Patel SR, White DP, Malhotra A, Stanchina ML, Ayas NT (March 2003). "Continuous positive airway pressure therapy for treating sleepiness in a diverse population with obstructive sleep apnea: results of a meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (5): 565–71. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.5.565. PMID 12622603.

- ^ Hsu AA, Lo C (December 2003). "Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in sleep apnoea". Respirology. 8 (4): 447–54. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00494.x. PMID 14708553.

- ^ "3 Top Medical Device Stocks to Buy Now". 18 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Franklin KA, Lindberg E (August 2015). "Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (8): 1311–1322. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4561280. PMID 26380759.