Sonic hedgehog protein (SHH) is encoded for by the SHH gene.[5] The protein is named after the video game character Sonic the Hedgehog.

This signaling molecule is key in regulating embryonic morphogenesis in all animals. SHH controls organogenesis and the organization of the central nervous system, limbs, digits and many other parts of the body. Sonic hedgehog is a morphogen that patterns the developing embryo using a concentration gradient characterized by the French flag model.[6] This model has a non-uniform distribution of SHH molecules which governs different cell fates according to concentration. Mutations in this gene can cause holoprosencephaly, a failure of splitting in the cerebral hemispheres,[7] as demonstrated in an experiment using SHH knock-out mice in which the forebrain midline failed to develop and instead only a single fused telencephalic vesicle resulted.[8]

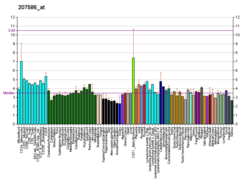

Sonic hedgehog still plays a role in differentiation, proliferation, and maintenance of adult tissues. Abnormal activation of SHH signaling in adult tissues has been implicated in various types of cancers including breast, skin, brain, liver, gallbladder and many more.[9]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000164690 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000002633 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

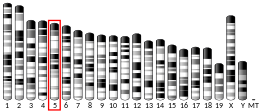

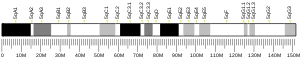

- ^ Marigo V, Roberts DJ, Lee SM, Tsukurov O, Levi T, Gastier JM, Epstein DJ, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Seidman CE (July 1995). "Cloning, expression, and chromosomal location of SHH and IHH: two human homologues of the Drosophila segment polarity gene hedgehog". Genomics. 28 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.1104. PMID 7590746.

- ^ Jaeger J, Martinez-Arias A (March 2009). "Getting the measure of positional information". PLOS Biology. 7 (3): e81. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000081. PMC 2661971. PMID 19338391.

- ^ Nanni L, Ming JE, Bocian M, Steinhaus K, Bianchi DW, Die-Smulders C, Giannotti A, Imaizumi K, Jones KL, Campo MD, Martin RA, Meinecke P, Pierpont ME, Robin NH, Young ID, Roessler E, Muenke M (December 1999). "The mutational spectrum of the sonic hedgehog gene in holoprosencephaly: SHH mutations cause a significant proportion of autosomal dominant holoprosencephaly". Human Molecular Genetics. 8 (13): 2479–2488. doi:10.1093/hmg/8.13.2479. PMID 10556296.

- ^ Blaess S, Szabó N, Haddad-Tóvolli R, Zhou X, Álvarez-Bolado G (2015-01-06). "Sonic hedgehog signaling in the development of the mouse hypothalamus". Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 8: 156. doi:10.3389/fnana.2014.00156. PMC 4285088. PMID 25610374.

- ^ Jeng KS, Chang CF, Lin SS (January 2020). "Sonic Hedgehog Signaling in Organogenesis, Tumors, and Tumor Microenvironments". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (3): 758. doi:10.3390/ijms21030758. PMC 7037908. PMID 31979397.