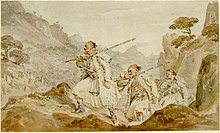

Souliot warriors in a watercolour by Charles Robert Cockerell entitled Albanian palikars in pursuit of an enemy (1813–1814)[1][2][3][4] | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 4,500[5][6] (1803, est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Souli | |

| Tetrachori | c. 3,250[5][6] |

| Eptachori | up to 1,250[5][6] |

| Languages | |

| Albanian Greek (from the 18th century onwards) | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity | |

The Souliotes were an Orthodox Christian Albanian tribal community in the area of Souli in Epirus from the 16th century to the beginning of the 19th century, who via their participation in the Greek War of Independence came to identify with the Greek nation.

They originated from Albanian clans that settled in the highlands of Thesprotia in the Late Middle Ages and established an autonomous confederation dominating a large number of neighbouring villages in the mountainous areas of Epirus, where they successfully resisted Ottoman rule for many years. At the height of its power, in the second half of the 18th century, the Souliote confederacy is estimated to have consisted of up to 4,500 inhabitants. After the revolution, they migrated to and settled in newly independent Greece, and assimilated into the Greek people. The Souliotes were followers of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. They spoke the Souliotic dialect of Albanian and learnt Greek through their interaction with Greek-speakers. They are known for their military prowess, their resistance to the local ruler Ali Pasha, and later for their contribution to the Greek cause in the revolutionary war against the Ottoman Empire under leaders such as Markos Botsaris and Kitsos Tzavelas.[7][8][9]

The first historical account of rebellious activity in Souli dates from 1685. During the 18th century, the Souliotes expanded their territory of influence. As soon as Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman ruler in 1789 he immediately launched successive expeditions against Souli. However, the numerical superiority of his troops was not enough. The siege against Souli was intensified from 1800 and in December 1803 the Souliotes concluded an armistice and agreed to abandon their homeland. Most of them were exiled in the Ionian Islands. On 4 December 1820, Ali Pasha constituted an anti-Ottoman coalition joined by the Souliotes, to which they contributed with 3,000 soldiers, mainly because he offered to allow the return of the Souliotes to their land, and partly by appeal to their shared Albanian origins.[10] After the defeat of Ali Pasha and with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, the Souliotes were among the first communities to take arms against the Ottomans. Following the successful struggle for independence, they settled in parts of the newly established Greek state and assimilated into the Greek nation, with many attaining high posts in the Greek government, including that of Prime Minister. Members of the Souliote diaspora participated in the national struggles for the incorporation of Souli to Greece, such as in the revolt of 1854 and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) with Ottoman rule ending in 1913.

- ^ Ελευθερία Νικολαΐδου (Eleutheria Nikolaidou) (1997). "Η Ήπειρος στον Αγώνα της Ανεξαρτησίας (Epirus in the Struggle for Independence)". In Μιχαήλ Σακελλαρίου (Michael Sakellariou) (ed.). Ηπειρος : 4000 χρόνια ελληνικής ιστορίας και πολιτισμού (Epirus: 4.000 years of Greek history and civilisation). Athens: Εκδοτική Αθηνών. p. 277.

Στήν εἰκόνα πολεμιστές Σουλιῶτες σέ χαλκογραφία τῶν μέσων τοῦ 19ου αἰ. (In the picture Souliote warriors from a 19th c. chalcography)

- ^ "drawing _ British Museum". Retrieved 2022-11-03.

Description: Albanian Palikars in pursuit of an enemy

- ^ "Σουλιώτες πολεμιστές καταδιώκουν τον εχθρό. - Hughes, Thomas Smart - Mε Tο Bλεμμα Των Περιγηηγητων - Τόποι - Μνημεία - Άνθρωποι - Νοτιοανατολική Ευρώπη - Ανατολική Μεσόγειος - Ελλάδα - Μικρά Ασία - Νότιος Ιταλία, 15ος - 20ός αιώνας". Retrieved 2022-11-03.

Πρωτότυπος τίτλος: View of Albanian palikars in pursuit of an enemy

- ^ Murawska-Muthesius 2021, pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b c Ψιμούλη 2006, p. 201

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

PsimouliPopulationPhDwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^

- NGL Hammond: Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon P., 1967, p. 24: "...they all fought equally well and none better than the Albanian-speaking Suliotes in Greek Epirus of whom Byron sang."

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Nikolopoulou299was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^

- Balázs Trencsényi, Michal Kopecek: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): The Formation of National Movements. Central European University Press, 2006, ISBN 963-7326-60-X, S. 173. “The Souliotes were Albanian by origin and Orthodox by faith”.

- Eric Hobsbawm: Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2. Edition. Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-43961-2, S. 65 “Swiss nationalism is, as we know, pluri-ethnic. For that matter, if we were to suppose that the Greek mountaineers who rose against the Turks in Byron's day were nationalists, which is admittedly improbable, we cannot fail to note that some of their most formidable fighters were not Hellenes but Albanians (the Souliotes).”

- Richard Clogg: Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. Hurst, Oxford 2002, S. 178. [Footnote] “The Souliotes were a warlike Albanian Christian community, which resisted Ali Pasha in Epirus in the years immediately preceding the outbreak the Greek War of Independence in 1821.”

- Miranda Vickers: The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 1-86064-541-0, S. 20. “The Suliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to that of the Catholic Mirdite tribe to the north”.

- Nicholas Pappas: Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries. Institute for Balkan Studies. Monograph Series, No. 219, Thessaloniki 1991, ISSN 0073-862X.[page needed][need quotation to verify]

- Fleming K. (2014), p.59

- André Gerolymatos: The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Basic Books, 2002, ISBN 0-465-02732-6, S. 141. “The Suliot dance of death is an integral image of the Greek revolution and it has been seared into the consciousness of Greek schoolchildren for generations. Many youngsters pay homage to the memory of these Orthodox Albanians each year by recreating the event in their elementary school pageants.”

- Henry Clifford Darby: Greece. Great Britain Naval Intelligence Division. University Press, 1944. “… who belong to the Cham branch of south Albanian Tosks (see volume I, pp. 363–5). In the mid-eighteenth century these people (the Souliotes) were a semi-autonomous community …”

- Arthur Foss (1978). Epirus. Faber. pp. 160–161. “The Souliots were a tribe or clan of Christian Albanians who settled among these spectacular but inhospitable mountains during the fourteenth or fifteenth century…. The Souliots, like other Albanians, were great dandies. They wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes thrown carelessly over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.”

- Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer (1983), "Of Suliots, Arnauts, Albanians and Eugène Delacroix". The Burlington Magazine. p. 487. “The Albanians were a mountain population from the region of Epirus, in the north-west part of the Ottoman Empire. They were predominantly Muslim. The Suliots were a Christian Albanian tribe, which in the eighteenth century settled in a mountainous area close to the town of Jannina. They struggled to remain independent and fiercely resisted Ali Pasha, the tyrannic ruler of Epirus. They were defeated in 1822 and, banished from their homeland, took refuge in the Ionian Islands. It was there that Lord Byron recruited a number of them to form his private guard, prior to his arrival in Missolonghi in 1824. Arnauts was the name given by the Turks to the Albanians”.

- ^ Fleming 2014, p. 47.