| Earth's ocean |

|---|

|

Main five oceans division: Further subdivision: Marginal seas |

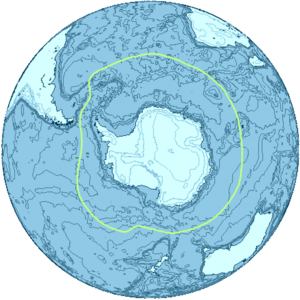

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean,[1][note 4] comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica.[5] With a size of 21,960,000 km2 (8,480,000 sq mi), it is the second-smallest of the five principal oceanic divisions, smaller than the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans, and larger than the Arctic Ocean.[6]

The maximum depth of the Southern Ocean, using the definition that it lies south of 60th parallel, was surveyed by the Five Deeps Expedition in early February 2019. The expedition's multibeam sonar team identified the deepest point at 60° 28' 46"S, 025° 32' 32"W, with a depth of 7,434 metres (24,390 ft). The expedition leader and chief submersible pilot Victor Vescovo, has proposed naming this deepest point the "Factorian Deep", based on the name of the crewed submersible DSV Limiting Factor, in which he successfully visited the bottom for the first time on February 3, 2019.[7]

By way of his voyages in the 1770s, James Cook proved that waters encompassed the southern latitudes of the globe. Yet, geographers have often disagreed on whether the Southern Ocean should be defined as a body of water bound by the seasonally fluctuating Antarctic Convergence - an oceanic zone where cold, northward flowing waters from the Antarctic mix with warmer Subantarctic waters,[8] or not defined at all, with its waters instead treated as the southern limits of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) finally settled the debate after the full importance of Southern Ocean overturning circulation had been ascertained, and the term Southern Ocean now defines the body of water which lies south of the northern limit of that circulation.[9]

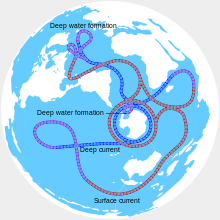

The Southern Ocean overturning circulation is important because it makes up the second half of the global thermohaline circulation, after the better known Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC).[10] Much like AMOC, it has also been substantially affected by climate change, in ways that have increased ocean stratification,[11] and which may also result in the circulation substantially slowing or even passing a tipping point and collapsing outright. The latter would have adverse impacts on global weather and the function of marine ecosystems here, unfolding over centuries.[12][13] The ongoing warming is already changing marine ecosystems here.[14]

- ^ EB (1878).

- ^ a b Sherwood, Mary Martha (1823), An Introduction to Geography, Intended for Little Children, 3rd ed., Wellington: F. Houlston & Son, p. 10

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 422.

- ^ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1843), Flora Antarctica: The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage, London: Reeve

- ^ "Geography – Southern Ocean". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

... the Southern Ocean has the unique distinction of being a large circumpolar body of water totally encircling the continent of Antarctica; this ring of water lies between 60 degrees south latitude and the coast of Antarctica and encompasses 360 degrees of longitude.

- ^ "Introduction – Southern Ocean". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

...As such, the Southern Ocean is now the fourth largest of the world's five oceans (after the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, and Indian Ocean, but larger than the Arctic Ocean).

- ^ "Explorer completes another historic submersible dive". For The Win. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Pyne, Stephen J. (1986). The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica. University of Washington Press.

- ^ "Do You Know the World's Newest Ocean?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "NOAA Scientists Detect a Reshaping of the Meridional Overturning Circulation in the Southern Ocean". NOAA. 29 March 2023.

- ^ Haumann, F. Alexander; Gruber, Nicolas; Münnich, Matthias; Frenger, Ivy; Kern, Stefan (September 2016). "Sea-ice transport driving Southern Ocean salinity and its recent trends". Nature. 537 (7618): 89–92. Bibcode:2016Natur.537...89H. doi:10.1038/nature19101. hdl:20.500.11850/120143. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 27582222. S2CID 205250191.

- ^ Lenton, T. M.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Loriani, S.; Abrams, J.F.; Lade, S.J.; Donges, J.F.; Milkoreit, M.; Powell, T.; Smith, S.R.; Zimm, C.; Buxton, J.E.; Daube, Bruce C.; Krummel, Paul B.; Loh, Zoë; Luijkx, Ingrid T. (2023). The Global Tipping Points Report 2023 (Report). University of Exeter.

- ^ Logan, Tyne (29 March 2023). "Landmark study projects 'dramatic' changes to Southern Ocean by 2050". ABC News.

- ^ Constable, Andrew J.; Melbourne-Thomas, Jessica; Corney, Stuart P.; Arrigo, Kevin R.; Barbraud, Christophe; Barnes, David K. A.; Bindoff, Nathaniel L.; Boyd, Philip W.; Brandt, Angelika; Costa, Daniel P.; Davidson, Andrew T. (2014). "Climate change and Southern Ocean ecosystems I: how changes in physical habitats directly affect marine biota". Global Change Biology. 20 (10): 3004–3025. Bibcode:2014GCBio..20.3004C. doi:10.1111/gcb.12623. ISSN 1365-2486. PMID 24802817. S2CID 7584865.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).