Srivijaya Kadatuan Śrīvijaya | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 671–1025 | |||||||||

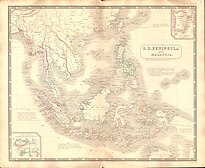

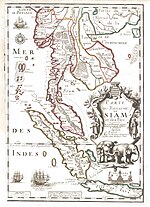

The maximum extent of Srivijaya around the 8th to the 11th century with a series of Srivijayan expeditions and conquest | |||||||||

Map of the expansion of the Srivijaya empire, beginning in Palembang in the 7th century, then extending to most of Sumatra, then expanding to Java, Riau Islands, Bangka Belitung, Singapore, Malay Peninsula (also known as: Kra Peninsula), Thailand, Cambodia, South Vietnam, Kalimantan, Sarawak, Brunei, Sabah, and ended as the Kingdom of Dharmasraya in Jambi in the 13th century. | |||||||||

| Capital | Palembang[1]: 295 | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Malay and Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy, mandala state | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

• Circa 683 AD | Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa | ||||||||

• Circa 775 | Dharmasetu | ||||||||

• Circa 792 | Samaratungga | ||||||||

• Circa 835 | Balaputra | ||||||||

• Circa 988 | Sri Cudamani Warmadewa | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Dapunta Hyang's expedition and expansion (Kedukan Bukit inscription) | c. 671 | ||||||||

| 1025 | |||||||||

| Currency | Early Nusantara coins | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Indonesia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

Srivijaya (Indonesian: Sriwijaya),[2]: 131 also spelled Sri Vijaya,[3][4] was a Buddhist thalassocratic[5] empire based on the island of Sumatra (in modern-day Indonesia) that influenced much of Southeast Asia.[6] Srivijaya was an important centre for the expansion of Buddhism from the 7th to 11th century AD. Srivijaya was the first polity to dominate much of western Maritime Southeast Asia. Due to its location, Srivijaya developed complex technology utilizing maritime resources. In addition, its economy became progressively reliant on the booming trade in the region, thus transforming it into a prestige goods-based economy.[7]

The earliest reference to it dates from the 7th century. A Tang dynasty Chinese monk, Yijing, wrote that he visited Srivijaya in 671 for six months.[8][9] The earliest known inscription in which the name Srivijaya appears also dates from the 7th century in the Kedukan Bukit inscription found near Palembang, Sumatra, dated 16 June 682.[10] Between the late 7th and early 11th century, Srivijaya rose to become a hegemon in Southeast Asia. It was involved in close interactions, often rivalries, with the neighbouring Mataram, Khom and Champa. Srivijaya's main foreign interest was nurturing lucrative trade agreements with China which lasted from the Tang to the Song dynasty. Srivijaya had religious, cultural and trade links with the Buddhist Pala of Bengal, as well as with the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East.

Although it was once thought of as a maritime empire, new research on available records suggests that Srivijaya was primarily a land-based polity rather than a maritime power; fleets were available but acted as logistical support to facilitate the projection of land power. In response to the change in the maritime Asian economy, and threatened by the loss of its dependencies, the kingdoms around the Strait of Malacca developed a naval strategy to delay their decline. The naval strategy was mainly punitive; this was done to coerce trading ships to be called to their port. Later, the naval strategy degenerated to raiding fleet.[11]

The kingdom may have disintegrated after 1025 CE following several major raids launched by the Chola Empire upon their ports.[12]: 110 After Srivijaya fell, it was largely forgotten. It was not until 1918 that French historian George Cœdès, of the French School of the Far East, formally postulated its existence.[13]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:02was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Coedeswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rausa-Gomez, Lourdes (20 January 1967). "Sri Vijaya and Madjapahit". Philippine Studies. 15 (1): 63–107. JSTOR 42720174.

- ^ Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (20 January 2024). "Śrī Vijaya". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient. 40 (2): 239–313. JSTOR 43733093.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kulkewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. p. 171. ISBN 981-4155-67-5.

- ^ Laet, Sigfried J. de; Herrmann, Joachim (1994). History of Humanity. Routledge.

- ^ Munoz. Early Kingdoms. p. 122.

- ^ Zain, Sabri. "Sejarah Melayu, Buddhist Empires".

- ^ Peter Bellwood; James J. Fox; Darrell Tryon (1995). Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. doi:10.22459/A.09.2006. ISBN 978-0-7315-2132-6.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:6was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

MUNOZ 117was invoked but never defined (see the help page).