| Stanislaus River | |

|---|---|

Stanislaus River at the historic covered bridge in Knights Ferry | |

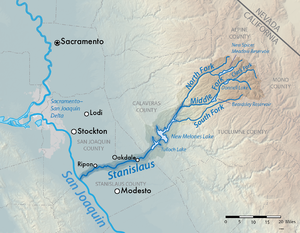

Map of the Stanislaus River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Counties | Alpine, Calaveras, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Tuolumne |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Middle Fork Stanislaus River–Kennedy Creek |

| • location | Near Leavitt Peak, Tuolumne County |

| • coordinates | 38°14′21″N 119°36′43″W / 38.23917°N 119.61194°W[1] |

| • elevation | 9,635 ft (2,937 m) |

| 2nd source | North Fork Stanislaus River |

| • location | Mosquito Lake, Alpine County |

| • coordinates | 38°30′54″N 119°54′52″W / 38.51500°N 119.91444°W[2] |

| • elevation | 8,075 ft (2,461 m) |

| Source confluence | Camp Nine |

| • location | near Hathaway Pines, Calaveras |

| • coordinates | 38°09′15″N 120°21′27″W / 38.15417°N 120.35750°W[3] |

| • elevation | 1,238 ft (377 m) |

| Mouth | San Joaquin River |

• location | Near Vernalis, San Joaquin |

• coordinates | 38°09′15″N 120°21′27″W / 38.15417°N 120.35750°W[3] |

• elevation | 20 ft (6.1 m) |

| Length | 95.9 mi (154.3 km)[4] |

| Basin size | 1,075 sq mi (2,780 km2)[5] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Ripon, about 15 mi (24 km) above the mouth[6] |

| • average | 952 cu ft/s (27.0 m3/s)[6] |

| • minimum | 0.11 cu ft/s (0.0031 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 62,500 cu ft/s (1,770 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Middle Fork Stanislaus River, Rose Creek, South Fork Stanislaus River |

| • right | North Fork Stanislaus River, Angels Creek, Black Creek |

The Stanislaus River is a tributary of the San Joaquin River in north-central California in the United States. The main stem of the river is 96 miles (154 km) long, and measured to its furthest headwaters it is about 150 miles (240 km) long. Originating as three forks in the high Sierra Nevada, the river flows generally southwest through the agricultural San Joaquin Valley to join the San Joaquin south of Manteca, draining parts of five California counties. The Stanislaus is known for its swift rapids and scenic canyons in the upper reaches, and is heavily used for irrigation, hydroelectricity and domestic water supply.

Originally inhabited by the Miwok group of Native Americans, the Stanislaus River was explored in the early 1800s by the Spanish, who conscripted indigenous people to work in the colonial mission and presidio systems. The river is named for Estanislao, who led a native uprising in Mexican-controlled California in 1828, but was ultimately defeated on the Stanislaus River (then known as the Río de los Laquisimes). During the California Gold Rush, the Stanislaus River was the destination of tens of thousands of gold seekers; many of them reached California via Sonora Pass, at the headwaters of the Middle Fork. Many miners and their families eventually settled along the lower Stanislaus River. The farms and ranches they established are now part of the richest agricultural region in the United States.[7]

Early mining companies were formed to channel Stanislaus River water to the gold diggings via elaborate canal and flume systems, which directly preceded the irrigation districts formed by farmers who sought a greater degree of river control. Starting in the early 1900s, many dams were built to store and divert water; these were often paired with hydro-power systems, whose revenues covered the high cost of the water projects. In the 1970s the construction of the federal New Melones Dam incited major opposition from recreation and environmental groups (documented on the Stanislaus River Archive), who protested the loss of one of the last free-flowing stretches of the Stanislaus. Although New Melones was eventually built, its completion is considered to have marked the end of large dam building in the United States.[8]

Water rights along the Stanislaus River are a controversial topic, with the senior rights of farmers coming into conflict with federal and state laws protecting endangered salmon and steelhead trout. The Stanislaus irrigation districts contend that diverting water for fish damages the local economy, especially in years of drought. Water managers have struggled to find a balance between competing needs, which also include groundwater recharge, flood control, and river-based recreation such as fishing and whitewater rafting.

- ^ "Kennedy Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ^ "North Fork Stanislaus River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ^ a b "Stanislaus River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1981-01-19. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 11, 2011

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

watershed profileswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Water Data Report 2013was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "2012 Census Profiles California Farmers and Agriculture: 9 California Counties Make Top 10 List for Ag Sales in the U.S." (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2014-05-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-05. Retrieved 2017-03-11. The 2012 United States Census of Agriculture ranked eight Central Valley counties in the top 10 for total agricultural sales. San Joaquin and Stanislaus Counties ranked 6th and 7th, respectively.

- ^ "New Melones Unit Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-03-11.