This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

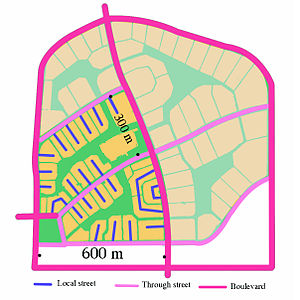

The street hierarchy is an urban planning technique for laying out road networks that exclude automobile through-traffic from developed areas. It is conceived as a hierarchy of roads that embeds the link importance of each road type in the network topology (the connectivity of the nodes to each other). Street hierarchy restricts or eliminates direct connections between certain types of links, for example residential streets and arterial roads, and allows connections between similar order streets (e.g. arterial to arterial) or between street types that are separated by one level in the hierarchy (e.g. arterial to highway and collector to arterial). By contrast, in many regular, traditional grid plans, as laid out, higher order roads (e.g. arterials) are connected by through streets of both lower order levels (e.g. local and collector). An ordering of roads and their classification can include several levels and finer distinctions as, for example, major and minor arterials or collectors.

At the lowest level of the hierarchy, cul-de-sac streets,[1] by definition non-connecting, link with the next order street, a primary or secondary "collector"—either a ring road that surrounds a neighbourhood, or a curvilinear "front-to-back" path—which in turn links with the arterial. Arterials then link with the intercity highways at strictly specified intervals at intersections that are either signalized or grade separated.

In places where grid networks were laid out in the pre-automotive 19th century, such as in the American Midwest, larger subdivisions have adopted a partial hierarchy, with two to five entrances off one or two main roads (arterials) thus limiting the links between them and, consequently, traffic through the neighbourhood.

Since the 1960s, street hierarchy has been the dominant network configuration of suburbs and exurbs in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the UK. It is less popular in Latin America, Western Europe, and China.

Large subdivisions may have three- or even four-tiered hierarchies, feeding into one or two wide arterials, which can be as wide as the ten lane Champs-Élysées or Wilshire Boulevard. Arterials at this level of traffic volume generally require no fewer than four lanes in width; and in large contemporary suburbs, such as Naperville, Illinois, or Irvine, California, are often eight or ten lanes wide. Adjacent street hierarchies are rarely connected to one another.