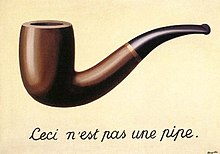

The Treachery of Images, by René Magritte (1929), featuring the declaration "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (lit. 'This is not a pipe') | |

| Years active | 1920s–1950s |

|---|---|

| Location | France, Belgium |

| Major figures | Breton, Carrington, Dalí, Ernst, Fini, Magritte, Oppenheim |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Part of a series on |

| Surrealism |

|---|

| Aspects |

| Groups |

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas.[1] Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality.[2][3][4] It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

Works of Surrealism feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur. However, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost (for instance, of the "pure psychic automatism" Breton speaks of in the first Surrealist Manifesto), with the works themselves being secondary, i.e., artifacts of surrealist experimentation.[5] Leader Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement. At the time, the movement was associated with political causes such as communism and anarchism. It was influenced by the Dada movement of the 1910s.[6]

The term "Surrealism" originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917.[7][8] However, the Surrealist movement was not officially established until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by French poet and critic André Breton succeeded in claiming the term for his group over a rival faction led by Yvan Goll, who had published his own surrealist manifesto two weeks prior.[9] The most important center of the movement was Paris, France. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, impacting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

- ^ Barnes, Rachel (2001). The 20th-Century art book (Reprinted. ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3542-6.

- ^ André Breton, Manifeste du surréalisme, various editions, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Ian Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 611, ISBN 0-19-953294-X.

- ^ "André Breton (1924), Manifesto of Surrealism". Tcf.ua.edu. 1924-06-08. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ Breton, André (1997). The Automatic Message (First. ed.). London: Atlas Press. ISBN 978-0-9477-5799-1.

- ^ Voorhies, James. "Surrealism". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "The movement started in 1917, that year of war and revolution, when the term was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire and when three young intellectuals, André Breton, Philipp Soupault and Louis Aragon, met each other in Paris and found that they shared the same overriding artistic principle: any art, in future, was only possible if it denied the validity of bourgeois sense and morals."— page 11 In: Haslam, Malcolm. The Real World of the Surrealists. New York: Galley Press / W.H.Smith Publishers, 1978.

- ^ "Guillaume Apollinaire having coined the term surréalisme in the spring of 1917, subtitled his play Le Mamelles de Tirésias, performed just before his death the following year, Drame surréaliste. It was in fact Apollinaire who first introduced Breton to Philippe Soupault at his 125 Boulevard St. Germaine apartment, meeting-place for most of the significant avant-garde figures of the day." p. 39 in David Gascoyne's Translator's Introduction to "The Magnetic Fields," included with "The Immaculate Conception," in Breton, André. The Automatic Message. Translated by David Gascoyne, Antony Melville, & Jon Graham. (London and Geurnsey: Atlas Press, 1997). ISBN 1-900565-01-3 & CIP available from The British Library.

- ^ Yvan Goll's manifesto preceded Breton's by fourteen days, although Breton eventually succeeded in claiming the term for his group. See Matthew S. Witkovsky, "Surrealism in the Plural: Guillaume Apollinaire, Ivan Goll and Devětsil in the 1920s" Papers of Surrealism, 2, Summer 2004, pp. 1–14.