| Syphilis | |

|---|---|

| |

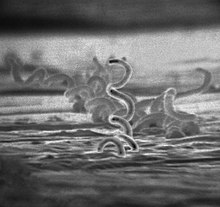

| Electron micrograph of Treponema pallidum bacteria | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulcer[1] |

| Causes | Treponema pallidum, usually spread by sex[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, dark field microscopy of infected fluid[2][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Many other diseases[2] |

| Prevention | Condoms, Long-term monogamous relationships[2] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[4] |

| Frequency | 45.4 million / 0.6% (2015, global)[5] |

| Deaths | 107,000 (2015, global)[6] |

Syphilis (/ˈsɪfəlɪs/) is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum.[1] The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent or tertiary.[1][2] The primary stage classically presents with a single chancre (a firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulceration usually between 1 cm and 2 cm in diameter) though there may be multiple sores.[2] In secondary syphilis, a diffuse rash occurs, which frequently involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.[2] There may also be sores in the mouth or vagina.[2] Latent syphilis has no symptoms and can last years.[2] In tertiary syphilis, there are gummas (soft, non-cancerous growths), neurological problems, or heart symptoms.[3] Syphilis has been known as "the great imitator" because it may cause symptoms similar to many other diseases.[2][3]

Syphilis is most commonly spread through sexual activity.[2] It may also be transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis.[2][7] Other diseases caused by Treponema bacteria include yaws (T. pallidum subspecies pertenue), pinta (T. carateum), and nonvenereal endemic syphilis (T. pallidum subspecies endemicum).[3] These three diseases are not typically sexually transmitted.[8] Diagnosis is usually made by using blood tests; the bacteria can also be detected using dark field microscopy.[2] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) recommends for all pregnant women to be tested.[2]

The risk of sexual transmission of syphilis can be reduced by using a latex or polyurethane condom.[2] Syphilis can be effectively treated with antibiotics.[4] The preferred antibiotic for most cases is benzathine benzylpenicillin injected into a muscle.[4] In those who have a severe penicillin allergy, doxycycline or tetracycline may be used.[4] In those with neurosyphilis, intravenous benzylpenicillin or ceftriaxone is recommended.[4] During treatment people may develop fever, headache, and muscle pains, a reaction known as Jarisch–Herxheimer.[4]

In 2015, about 45.4 million people had syphilis infections,[5] of which six million were new cases.[9] During 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.[6][10] After decreasing dramatically with the availability of penicillin in the 1940s, rates of infection have increased since the turn of the millennium in many countries, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[3][11] This is believed to be partly due to unsafe drug use, increased prostitution, and decreased use of condoms.[12][13][14]

- ^ a b c d Ghanem KG, Hook EW (2020). "303. Syphilis". In Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 1983–1989. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Syphilis – CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed)". CDC. 2 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Kent ME, Romanelli F (February 2008). "Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1345/aph.1K086. PMID 18212261. S2CID 23899851.

- ^ a b c d e f "Syphilis". CDC. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Woods, CR (June 2009). "Congenital syphilis-persisting pestilence". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 28 (6): 536–537. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ac8a69. PMID 19483520.

- ^ "Pinta". NORD. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, et al. (2015). "Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143304. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043304N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. PMC 4672879. PMID 26646541.

- ^ Lozano R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Franzen C (December 2008). "Syphilis in composers and musicians – Mozart, Beethoven, Paganini, Schubert, Schumann, Smetana". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 27 (12): 1151–57. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0571-x. PMID 18592279. S2CID 947291.

- ^ Coffin L, Newberry A, Hagan H, Cleland C, Des Jarlais D, Perlman D (January 2010). "Syphilis in Drug Users in Low and Middle Income Countries". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 21 (1): 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.008. PMC 2790553. PMID 19361976.

- ^ Gao L, Zhang, L., Jin, Q (September 2009). "Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 85 (5): 354–58. doi:10.1136/sti.2008.034702. PMID 19351623. S2CID 24198278.

- ^ Karp G, Schlaeffer, F., Jotkowitz, A., Riesenberg, K. (January 2009). "Syphilis and HIV co-infection". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 20 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.002. PMID 19237085.