This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (September 2023) |  |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

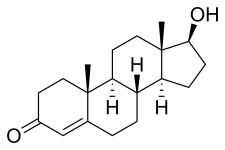

17β-Hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1S,3aS,3bR,9aR,9bS,11aS)-1-Hydroxy-9a,11a-dimethyl-1,2,3,3a,3b,4,5,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-7H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-one | |

| Other names

Androst-4-en-17β-ol-3-one

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.336 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C19H28O2 | |

| Molar mass | 288.431 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 151.0 °C (303.8 °F; 424.1 K)[1] |

| Pharmacology | |

| G03BA03 (WHO) | |

| License data | |

| Transdermal (gel, cream, solution, patch), by mouth (as testosterone undecanoate), in the cheek, intranasal (gel), intramuscular injection (as esters), subcutaneous pellets | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Oral: very low (due to extensive first pass metabolism) | |

| 97.0–99.5% (to SHBG and albumin)[2] | |

| Liver (mainly reduction and conjugation) | |

| 30–45 minutes[citation needed] | |

| Urine (90%), feces (6%) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone and androgen in males.[3] In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of male reproductive tissues such as testicles and prostate, as well as promoting secondary sexual characteristics such as increased muscle and bone mass, and the growth of body hair. It is associated with increased aggression, sex drive, dominance, courtship display, and a wide range of behavioral characteristics.[4] In addition, testosterone in both sexes is involved in health and well-being, where it has a significant effect on overall mood, cognition, social and sexual behavior, metabolism and energy output, the cardiovascular system, and in the prevention of osteoporosis.[5][6] Insufficient levels of testosterone in men may lead to abnormalities including frailty, accumulation of adipose fat tissue within the body, anxiety and depression, sexual performance issues, and bone loss.

Excessive levels of testosterone in men may be associated with hyperandrogenism, higher risk of heart failure, increased mortality in men with prostate cancer,[7] and male pattern baldness.

Testosterone is a steroid hormone from the androstane class containing a ketone and a hydroxyl group at positions three and seventeen respectively. It is biosynthesized in several steps from cholesterol and is converted in the liver to inactive metabolites.[8] It exerts its action through binding to and activation of the androgen receptor.[8] In humans and most other vertebrates, testosterone is secreted primarily by the testicles of males and, to a lesser extent, the ovaries of females. On average, in adult males, levels of testosterone are about seven to eight times as great as in adult females.[9] As the metabolism of testosterone in males is more pronounced, the daily production is about 20 times greater in men.[10][11] Females are also more sensitive to the hormone.[12][page needed]

In addition to its role as a natural hormone, testosterone is used as a medication to treat hypogonadism and breast cancer.[13] Since testosterone levels decrease as men age, testosterone is sometimes used in older men to counteract this deficiency. It is also used illicitly to enhance physique and performance, for instance in athletes.[14] The World Anti-Doping Agency lists it as S1 Anabolic agent substance "prohibited at all times".[15]

- ^ Haynes WM, ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 3.304. ISBN 978-1-4398-5511-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

MelmedPolonsky2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Understanding the risks of performance-enhancing drugs". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Korenman SG (February 1987). "Biological actions of androgens". Endocrine Reviews. 8 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1210/edrv-8-1-1. PMID 3549275.

- ^ Bassil N, Alkaade S, Morley JE (June 2009). "The benefits and risks of testosterone replacement therapy: a review". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 5 (3): 427–48. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s3025. PMC 2701485. PMID 19707253.

- ^ Tuck SP, Francis RM (2009). "Testosterone, bone and osteoporosis". Advances in the Management of Testosterone Deficiency. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 37. pp. 123–32. doi:10.1159/000176049. ISBN 978-3-8055-8622-1. PMID 19011293.

- ^ Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ (August 1996). "Prospective study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 88 (16): 1118–1126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.1837. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.16.1118. PMID 8757191.

- ^ a b Luetjens CM, Weinbauer GF (2012). "Chapter 2: Testosterone: Biosynthesis, transport, metabolism and (non-genomic) actions". In Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S (eds.). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–32. ISBN 978-1-107-01290-5.

- ^ Torjesen PA, Sandnes L (March 2004). "Serum testosterone in women as measured by an automated immunoassay and a RIA". Clinical Chemistry. 50 (3): 678, author reply 678–9. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2003.027565. PMID 14981046.

- ^ Southren AL, Gordon GG, Tochimoto S, Pinzon G, Lane DR, Stypulkowski W (May 1967). "Mean plasma concentration, metabolic clearance and basal plasma production rates of testosterone in normal young men and women using a constant infusion procedure: effect of time of day and plasma concentration on the metabolic clearance rate of testosterone". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 27 (5): 686–94. doi:10.1210/jcem-27-5-686. PMID 6025472.

- ^ Southren AL, Tochimoto S, Carmody NC, Isurugi K (November 1965). "Plasma production rates of testosterone in normal adult men and women and in patients with the syndrome of feminizing testes". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 25 (11): 1441–50. doi:10.1210/jcem-25-11-1441. PMID 5843701.

- ^ Dabbs M, Dabbs JM (2000). Heroes, rogues, and lovers: testosterone and behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135739-5.

- ^ "Testosterone". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. December 4, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Liverman CT, Blazer DG, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy) (2004). "Introduction". Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions (Report). National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ "What is Prohibited". World Anti-Doping Agency. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2021.