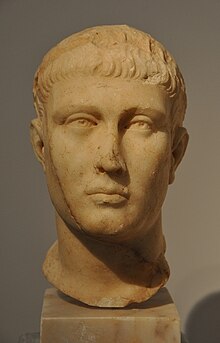

| Theodosius the Great | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Augustus | 19 January 379 – 17 January 395[ii] | ||||

| Predecessor | Valens | ||||

| Successor | |||||

| Co-rulers | See list

| ||||

| Born | 11 January 347 Cauca[6] or Italica,[7] in Hispania (present-day Spain) | ||||

| Died | 17 January 395 (aged 48) Mediolanum, Roman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Church of the Holy Apostles, Istanbul, Turkey | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Theodosian | ||||

| Father | Count Theodosius | ||||

| Mother | Thermantia | ||||

| Religion | Nicene Christianity | ||||

Theodosius I (‹See Tfd›Greek: Θεοδόσιος Theodosios; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also known as Theodosius the Great, was a Roman emperor from 379 to 395. He won two civil wars and was instrumental in establishing the Nicene Creed as the orthodox doctrine for Nicene Christianity. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire before its administration was permanently split between the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. He ended the Gothic War (376–382) with terms disadvantageous to the empire, with the Goths remaining within Roman territory but as nominal allies with political autonomy.

Born in Hispania, Theodosius was the son of a high-ranking general of the same name, Count Theodosius, under whose guidance he rose through the ranks of the Roman army. Theodosius held independent command in Moesia in 374, where he had some success against the invading Sarmatians. Not long afterwards, he was forced into retirement, and his father was executed under obscure circumstances. Theodosius soon regained his position following a series of intrigues and executions at Emperor Gratian's court. In 379, after the eastern Roman emperor Valens was killed at the Battle of Adrianople against the Goths, Gratian appointed Theodosius as a successor with orders to take charge of the military emergency. The new emperor's resources and depleted armies were not sufficient to drive the invaders out; in 382 the Goths were allowed to settle south of the Danube as autonomous allies of the empire. In 386, Theodosius signed a treaty with the Sasanian Empire which partitioned the long-disputed Kingdom of Armenia and secured a durable peace between the two powers.[9]

Theodosius was a strong adherent of the Christian doctrine of consubstantiality and an opponent of Arianism. He convened a council of bishops at the First Council of Constantinople in 381, which confirmed the former as orthodoxy and the latter as a heresy. Although Theodosius interfered little in the functioning of traditional pagan cults and appointed non-Christians to high offices, he failed to prevent or punish the damaging of several Hellenistic temples of classical antiquity, such as the Serapeum of Alexandria, by Christian zealots. During his earlier reign, Theodosius ruled the eastern provinces, while the west was overseen by the emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, whose sister he married. Theodosius sponsored several measures to improve his capital and main residence, Constantinople, most notably his expansion of the Forum Tauri, which became the biggest public square known in antiquity.[10] Theodosius marched west twice, in 388 and 394, after both Gratian and Valentinian had been killed, to defeat the two pretenders, Magnus Maximus and Eugenius, who rose to replace them. Theodosius's final victory in September 394 made him master of the entire empire; he died a few months later and was succeeded by his two sons, Arcadius in the eastern half of the empire and Honorius in the west.

Theodosius was said to have been a diligent administrator, austere in his habits, merciful, and a devout Christian.[11][12] For centuries after his death, Theodosius was regarded as a champion of Christian orthodoxy who decisively stamped out paganism. Modern scholars tend to see this as an interpretation of history by Christian writers more than an accurate representation of actual history. He is fairly credited with presiding over a revival in classical art that some historians have termed a "Theodosian renaissance".[13] Although his pacification of the Goths secured peace for the Empire during his lifetime, their status as an autonomous entity within Roman borders caused problems for succeeding emperors. Theodosius has also received criticism for defending his own dynastic interests at the cost of two civil wars.[14] His two sons proved weak and incapable rulers, and they presided over a period of foreign invasions and court intrigues, which heavily weakened the empire. The descendants of Theodosius ruled the Roman world for the next six decades, and the east–west division endured until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century.

- ^ Ruiz, María Pilar García; Puertas, Alberto J. Quiroga (2021). Emperors and Emperorship in Late Antiquity. Brill. pp. 160, 165. ISBN 978-90-04-44692-2.

- ^ Lenaghan, J. (2012a). "High imperial togate statue and re-cut portrait head of emperor. Aphrodisias (Caria)". Last Statues of Antiquity. LSA-196.

- ^ Smith & Ratté, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Weitzmann, Kurt (1977). Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Ar. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780870991790.

- ^ Lenaghan, J. (2012b). "Portrait head of Emperor, Theodosius II (?). Unknown provenance. Fifth century". Last Statues of Antiquity. LSA-453.

- ^ Hydatius and Zosimus

- ^ Marcellinus Comes and Jordanes

- ^ Bagnall et al., pp. 36–40.

- ^ Simon Hornblower, Who's Who in the Classical World (Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 386–387

- ^ Lippold, Adolf (2022). "Theodosius I". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Epitome de Caesaribus 48. 8–19

- ^ Gibbon, Decline and Fall, chapter 27

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, pp. 1482, 1484

- ^ Woods 2023, Family and Succession.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-roman> tags or {{efn-lr}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-roman}} template or {{notelist-lr}} template (see the help page).