| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Third-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, gaining prominence in the decades leading up to the fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second wave, Gen X third-wave feminists born in the 1960s and 1970s embraced diversity and individualism in women, and sought to redefine what it meant to be a feminist . The third wave saw the emergence of new feminist currents and theories, such as intersectionality, sex positivity, vegetarian ecofeminism, transfeminism, and postmodern feminism. According to feminist scholar Elizabeth Evans, the "confusion surrounding what constitutes third-wave feminism is in some respects its defining feature."

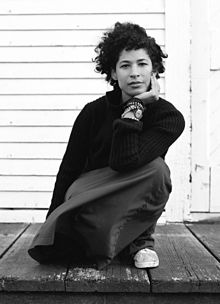

The third wave is traced to Anita Hill's televised testimony in 1991 to an all-male all-white Senate Judiciary Committee that the judge Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her. Rebecca Walker is credited with coining the term ‘third wave’ feminism, who responded to Thomas's appointment to the Supreme Court with an article in Ms. magazine, "Becoming the Third Wave" (1992). She wrote:

“So I write this as a plea to all women, especially women of my generation: Let Thomas' confirmation serve to remind you, as it did me, that the fight is far from over. Let this dismissal of a woman's experience move you to anger. Turn that outrage into political power. Do not vote for them unless they work for us. Do not have sex with them, do not break bread with them, do not nurture them if they don't prioritize our freedom to control our bodies and our lives. I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.” Walker sought to emphasize that third-wave feminism was not merely a reaction but a movement with distinct goals, as the feminist cause required continued activism. The term intersectionality to describe the idea that women experience "layers of oppression" caused, for example, by gender, race, and class had been introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, and it was during the third wave that the concept flourished.

In addition, third-wave feminism is traced to the emergence of the riot grrrl feminist punk subculture in Olympia, Washington, in the early 1990s. As feminists came online in the late 1990s and early 2000s and reached a global audience with blogs and e-zines, they broadened their goals, focusing on abolishing gender-role stereotypes and expanding feminism to include women with diverse racial and cultural identities.

History[edit]

Further information: First-wave feminism, Second-wave feminism, Feminist sex wars, and Fourth-wave feminism

The advances achieved by second-wave feminists provided a foundation for the goals and directions of third-wave feminism. The gains included Title IX (equal access to education), public discussion about the abuse and rape of women, access to contraception and other reproductive services (including the legalization of abortion as seen in Roe v Wade), the creation and enforcement of sexual-harassment policies for women in the workplace, the creation of domestic-abuse shelters for women and children, child-care services, educational funding for young women, and women's studies programs.

Feminists of color such as Gloria E. Anzaldúa, bell hooks, Cherríe Moraga, Audre Lorde, Maxine Hong Kingston, Leslie Marmon Silko and the members of the Combahee River Collective sought to negotiate a space within feminist thought for consideration of race. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa had published the anthology This Bridge Called My Back (1981), which, along with All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave (1982), edited by Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith, argued that second-wave feminism had focused primarily on the problems of white women. The emphasis on the intersection between race and gender became increasingly prominent. A very well known group from the 1970s and 1990s known as the Combahee River Collective decided to take this to heart and put themselves into action. The Combahee River Collective was a Black feminist organization active from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, founded by activists including Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, and Demita Frazier in Boston. Named after the Combahee River Raid led by Harriet Tubman during the Civil War, which freed hundreds of enslaved people, the collective embodied a commitment to intersectional analysis and liberation from multiple forms of oppression.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the feminist sex wars arose as a reaction against the radical feminism of the second wave and its views on sexuality, countering with a concept of "sex-positivity", and heralding the third wave.

Another crucial point for the start of the third wave is the publication in 1990 of Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity by Judith Butler, which soon became one of the most influential works of contemporary feminist theory. In it, Butler argued against homogenizing conceptions of "women", which had a normative and exclusionary effect not only in the social world more broadly but also within feminism. This was the case not only for racialized or working-class women, but also for masculine, lesbian, or non-binary women. Butler’s theory of gender as performativity suggests, posited that gender works by enforcing a series of repetitions of verbal and non-verbal acts that generate the "illusion" of a coherent and intelligible gender expression and identity, which would otherwise lack any essential property. Lastly, Butler developed the claim that there is no "natural" sex, but that what we call as such is always already culturally mediated, and therefore inseparable from gender. These views were foundational for the field of queer theory, and played a major role in the development of third-wave feminist theories and practices.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (January 1992). "Becoming the Third Wave" (PDF). Ms.: 39–41. ISSN 0047-8318. OCLC 194419734. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-15. Retrieved 2016-10-13.