| Tibetan Plateau | |

|---|---|

| 青藏高原 (Qīng–Zàng Gāoyuán, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau) | |

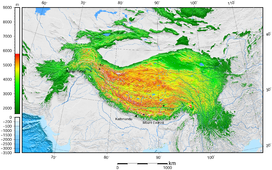

The Tibetan Plateau lies between the Himalayan range to the south and the Taklamakan Desert to the north. (Composite image) | |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 2,500 km (1,600 mi) |

| Width | 1,000 km (620 mi) |

| Area | 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| |

| Location | |

| Range coordinates | 33°N 88°E / 33°N 88°E |

The Tibetan Plateau,[a] also known as Qinghai–Tibet Plateau[b] and Qing–Zang Plateau,[c] is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South, and East Asia.[d]. Geographically, it is located to the north of Himalayas and the Indian subcontinent, and to the south of Tarim Basin and Mongolian Plateau. Geopolitically, it covers most of the Tibet Autonomous Region, most of Qinghai, western half of Sichuan, Southern Gansu provinces in Western China, southern Xinjiang, Bhutan, the Indian regions of Ladakh and Lahaul and Spiti (Himachal Pradesh) as well as Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan, northwestern Nepal, eastern Tajikistan and southern Kyrgyzstan. It stretches approximately 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north to south and 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) east to west. It is the world's highest and largest plateau above sea level, with an area of 2,500,000 square kilometres (970,000 sq mi).[13] With an average elevation exceeding 4,500 metres (14,800 ft)[citation needed] and being surrounded by imposing mountain ranges that harbor the world's two highest summits, Mount Everest and K2, the Tibetan Plateau is often referred to as "the Roof of the World".[14]

The Tibetan Plateau contains the headwaters of the drainage basins of most of the streams and rivers in surrounding regions. This includes the three longest rivers in Asia (the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong). Its tens of thousands of glaciers and other geographical and ecological features serve as a "water tower" storing water and maintaining flow. It is sometimes termed the Third Pole because its ice fields contain the largest reserve of fresh water outside the polar regions. The impact of climate change on the Tibetan Plateau is of ongoing scientific interest.[15][16][17][18]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Wang, Zhaoyin; Li, Zhiwei; Xu, Mengzhen; Yu, Guoan (30 March 2016). River Morphodynamics and Stream Ecology of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. CRC Press.

- ^ Jones, J.A.; Liu, Changming; Woo, Ming-Ko; Kung, Hsiang-Te (6 December 2012). Regional Hydrological Response to Climate Change. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 360.

- ^ "हिमालयी क्षेत्र में जीवन यापन पर रिसर्च करेंगे अमेरिका और भारत".

- ^ "In Little Tibet, a story of how displaced people rebuilt life in a distant land". 18 February 2020.

- ^ Illustrated Atlas of the World (1986) Rand McNally & Company. ISBN 0-528-83190-9 pp. 164–65

- ^ Atlas of World History (1998 ) HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7230-1025-0 p. 39

- ^ "The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia (Christopher Beckwith)". Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ Hopkirk 1983, p. 1

- ^ Peregrine, Peter Neal & Melvin Ember, etc. (2001). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: East Asia and Oceania, Volume 3. Springer. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-306-46257-3.

- ^ Morris, Neil (2007). North and East Asia. Heinemann-Raintree Library. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4034-9898-4.

- ^ Webb, Andrew Alexander Gordon (2007). Contractional and Extensional Tectonics During the India-Asia Collision. ProQuest LLC. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-549-50627-0.

- ^ Marston, Sallie A.; Paul L. Knox, Diana M. Liverman (2002). World regions in global context: peoples, places, and environments. Prentice Hall. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-13-022484-2.

- ^ "Natural World: Deserts". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 12 January 2006.

- ^ "Asia: Physical Geography". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Leslie Hook (30 August 2013). "Tibet: life on the climate front line". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Liu, Xiaodong; Chen (2000). "Climatic warming in the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades". International Journal of Climatology. 20 (14): 1729–1742. Bibcode:2000IJCli..20.1729L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.669.5900. doi:10.1002/1097-0088(20001130)20:14<1729::aid-joc556>3.0.co;2-y – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Ni, Jian (2000). "A Simulation of Biomes on the Tibetan Plateau and Their Responses to Global Climate Change". Mountain Research and Development. 20 (1): 80–89. doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2000)020[0080:ASOBOT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 128916992.

- ^ Cheng, Guodong; Wu (8 June 2007). "Responses of permafrost to climate change and their environmental significance, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau". Journal of Geophysical Research. 112 (F2): F02S64755. Bibcode:2007JGRF..112.2S03C. doi:10.1029/2006JF000631. S2CID 14450823.