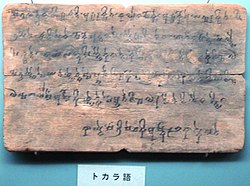

| Tocharian script | |

|---|---|

Kizil Caves standing Buddha. Often attributed in the past to the 7th century AD,[1] but now carbon dated to AD 245-340.[2] Tocharian B inscription reading: Se pañäkte saṅketavattse ṣarsa papaiykau "This Buddha was painted by the hand of Sanketava".[3][4][5][6] | |

| Script type | |

Time period | 8th century |

| Languages | Tocharian languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Gupta, Tamil-Brahmi, Bhattiprolu, Sinhala |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Tocharian script,[7] also known as Central Asian slanting Gupta script or North Turkestan Brāhmī,[8] is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. Part of the Brahmic scripts, it is a version of the Indian Brahmi script. It is used to write the Central Asian Indo-European Tocharian languages, mostly from the 8th century (with a few earlier ones, probably as early as AD 300)[9] that were written on palm leaves, wooden tablets and Chinese paper, preserved by the extremely dry climate of the Tarim Basin. Samples of the language have been discovered at sites in Kucha and Karasahr, including many mural inscriptions. Mistakenly identifying the speakers of this language with the Tokharoi people of Tokharistan (the Bactria of the Greeks), early authors called these languages "Tocharian". This naming has remained, although the names Agnean and Kuchean have been proposed as a replacement.[10][7]

Tocharian A and B are not mutually intelligible. Properly speaking, based on the tentative interpretation of twqry as related to Tokharoi, only Tocharian A may be referred to as Tocharian, while Tocharian B could be called Kuchean (its native name may have been kuśiññe), but since their grammars are usually treated together in scholarly works, the terms A and B have proven useful. A common Proto-Tocharian language must precede the attested languages by several centuries, probably dating to the 1st millennium BC. Given the small geographical range of and the lack of secular texts in Tocharian A, it might alternatively have been a liturgical language, the relationship between the two being similar to that between Classical Chinese and Mandarin. However, the lack of a secular corpus in Tocharian A is by no means definite, due to the fragmentary preservation of Tocharian texts in general.

- ^ Härtel, Herbert; Yaldiz, Marianne; Kunst (Germany), Museum für Indische; N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York (1982). Along the Ancient Silk Routes: Central Asian Art from the West Berlin State Museums : an Exhibition Lent by the Museum Für Indische Kunst, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-87099-300-8.

- ^ Waugh (Historian, University of Washington), Daniel C. "MIA Berlin: Turfan Collection: Kizil". depts.washington.edu.

- ^ Härtel, Herbert; Yaldiz, Marianne; Kunst (Germany), Museum für Indische; N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York (1982). Along the Ancient Silk Routes: Central Asian Art from the West Berlin State Museums : an Exhibition Lent by the Museum Für Indische Kunst, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-87099-300-8.

- ^ Le Coq, Albert von. Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien : vol.5. p. 10.

- ^ "A dictionary of Tocharian B". www.win.tue.nl.

- ^ In Ashokan Brahmi: 𑀲𑁂𑀧𑀜𑀓𑁆𑀢𑁂 𑀲𑀡𑁆𑀓𑁂𑀢𑀯𑀝𑁆𑀲𑁂 𑀱𑀭𑁆𑀲 𑀧𑀧𑁃𑀬𑁆𑀓𑁅

- ^ a b Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet A Key To The History Of Mankind. pp. 347–348.

- ^ "BRĀHMĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ Earliest paintings from Kizil Caves with Tocharian inscriptions, now carbon dated to AD 245-340, see Waugh (Historian, University of Washington), Daniel C. "MIA Berlin: Turfan Collection: Kizil". depts.washington.edu.

- ^ Namba Walter, Mariko (October 1998). "Tokharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E." (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 85: 2-4.