| Toxoplasma gondii | |

|---|---|

| |

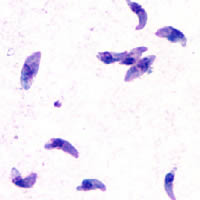

| Giemsa stained T. gondii tachyzoites, 1000× magnification | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Conoidasida |

| Order: | Eucoccidiorida |

| Family: | Sarcocystidae |

| Subfamily: | Toxoplasmatinae |

| Genus: | Toxoplasma Nicolle & Manceaux, 1909[2] |

| Species: | T. gondii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle & Manceaux, 1908)[1]

| |

Toxoplasma gondii (/ˈtɒksəˌplæzmə ˈɡɒndi.aɪ, -iː/) is a parasitic protozoan (specifically an apicomplexan) that causes toxoplasmosis.[3] Found worldwide, T. gondii is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals,[4]: 1 but felids are the only known definitive hosts in which the parasite may undergo sexual reproduction.[5][6]

In rodents, T. gondii alters behavior in ways that increase the rodents' chances of being preyed upon by felids.[7][8][9] Support for this "manipulation hypothesis" stems from studies showing that T. gondii-infected rats have a decreased aversion to cat urine while infection in mice lowers general anxiety, increases explorative behaviors and increases a loss of aversion to predators in general.[7][10] Because cats are one of the only hosts within which T. gondii can sexually reproduce, such behavioral manipulations are thought to be evolutionary adaptations that increase the parasite's reproductive success since rodents that do not avoid cat habitations will more likely become cat prey.[7] The primary mechanisms of T. gondii–induced behavioral changes in rodents occur through epigenetic remodeling in neurons that govern the relevant behaviors (e.g. hypomethylation of arginine vasopressin-related genes in the medial amygdala, which greatly decrease predator aversion).[11][12]

In humans, particularly infants and those with weakened immunity, T. gondii infection is generally asymptomatic but may lead to a serious case of toxoplasmosis.[13][4] T. gondii can initially cause mild, flu-like symptoms in the first few weeks following exposure, but otherwise, healthy human adults are asymptomatic.[14][13][4] This asymptomatic state of infection is referred to as a latent infection, and it has been associated with numerous subtle behavioral, psychiatric, and personality alterations in humans.[14][15][16] Behavioral changes observed between infected and non-infected humans include a decreased aversion to cat urine (but with divergent trajectories by gender) and an increased risk of schizophrenia.[17] Preliminary evidence has suggested that T. gondii infection may induce some of the same alterations in the human brain as those observed in rodents.[18][19][9][20][21][22] Many of these associations have been strongly debated and newer studies have found them to be weak, concluding:[23]

On the whole, there was little evidence that T. gondii was related to increased risk of psychiatric disorder, poor impulse control, personality aberrations, or neurocognitive impairment.

However, there is evidence that T. Gondii may cause suicidal ideation and suicide in humans.[24]

T. gondii is one of the most common parasites in developed countries;[25][26] serological studies estimate that up to 50% of the global population has been exposed to, and may be chronically infected with, T. gondii; although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.[14][27] Estimates have shown the highest IgG seroprevalence to be in Ethiopia, at 64.2%, as of 2018.[28]

- ^ Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. (1908). "Sur une infection à corps de Leishman (ou organismes voisins) du Gondi". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 147 (2): 763–66.

- ^ Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. (1909). "Sur un Protozoaire nouveau du Gondi". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 148 (1): 369–72.

- ^ Dardé, M. L.; Ajzenberg, D.; Smith, J. (2011). "Population structure and epidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii". In Weiss, L. M.; Kim, K. (eds.). Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods. Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York: Elsevier. pp. 49–80. doi:10.1016/B978-012369542-0/50005-2. ISBN 9780123695420.

- ^ a b c Dubey, J. P. (2010). "General Biology". Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans (2nd ed.). Boca Raton / London / New York: Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 1–20. ISBN 9781420092370. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "CDC - Toxoplasmosis - Biology". 17 March 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Knoll, Laura J.; Dubey, J. P.; Wilson, Sarah K.; Genova, Bruno Martorelli Di (1 July 2019). "Intestinal delta-6-desaturase activity determines host range for Toxoplasma sexual reproduction". bioRxiv. 17 (8): 688580. doi:10.1101/688580. PMC 6701743. PMID 31430281.

- ^ a b c Berdoy, M.; Webster, J. P.; Macdonald, D. W. (August 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 267 (1452): 1591–94. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.

- ^ Webster, J. P. (May 2007). "The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: playing cat and mouse". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 752–756. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl073. PMC 2526137. PMID 17218613.

- ^ a b Webster, J. P.; Kaushik, M.; Bristow, G. C.; McConkey, G. A. (January 2013). "Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour?". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (Pt 1): 99–112. doi:10.1242/jeb.074716. PMC 3515034. PMID 23225872.

- ^ Boillat, M.; Hammoudi, P. M.; Dogga, S. K.; Pagès, S.; Goubran, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Soldati-Favre, D. (2020). "Neuroinflammation-associated Aspecific Manipulation of Mouse Predator Fear by Toxoplasma gondii". Cell Reports. 30 (2). pp. 320–334.e6. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.019. PMC 6963786. PMID 31940479.

- ^ Hari Dass, S. A.; Vyas, A. (December 2014). "Toxoplasma gondii infection reduces predator aversion in rats through epigenetic modulation in the host medial amygdala". Molecular Ecology. 23 (24): 6114–22. Bibcode:2014MolEc..23.6114H. doi:10.1111/mec.12888. PMID 25142402. S2CID 45290208.

- ^ Flegr, J.; Markoš, A. (December 2014). "Masterpiece of epigenetic engineering – how Toxoplasma gondii reprogrammes host brains to change fear to sexual attraction". Molecular Ecology. 23 (24): 5934–5936. Bibcode:2014MolEc..23.5934F. doi:10.1111/mec.13006. PMID 25532868. S2CID 17253786.

- ^ a b "CDC Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) Disease". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Flegr, J.; Prandota, J.; Sovičková, M.; Israili, Z. H. (March 2014). "Toxoplasmosis – a global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e90203. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990203F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090203. PMC 3963851. PMID 24662942.

Toxoplasmosis is becoming a global health hazard as it infects 30–50% of the world human population. Clinically, the life-long presence of the parasite in tissues of a majority of infected individuals is usually considered asymptomatic. However, a number of studies show that this 'asymptomatic infection' may also lead to development of other human pathologies. ... The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis correlated with various disease burden. Statistical associations does not necessarily mean causality. The precautionary principle suggests, however, that possible role of toxoplasmosis as a triggering factor responsible for development of several clinical entities deserves much more attention and financial support both in everyday medical practice and future clinical research.

- ^ Cook, T. B.; Brenner, L. A.; Cloninger, C. R.; Langenberg, P.; Igbide, A.; Giegling, I.; Hartmann, A. M.; Konte, B.; Friedl, M.; Brundin, L.; Groer, M. W.; Can, A.; Rujescu, D.; Postolache, T. T. (January 2015). ""Latent" infection with Toxoplasma gondii: association with trait aggression and impulsivity in healthy adults". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 60: 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.019. PMID 25306262.

- ^ Flegr, J. (January 2013). "Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (Pt 1): 127–33. doi:10.1242/jeb.073635. PMID 23225875.

- ^ Burgdorf, K. S.; Trabjerg, B. B.; Pedersen, M. G.; Nissen, J.; Banasik, K.; Pedersen, O. B.; et al. (2019). "Large-scale study of Toxoplasma and Cytomegalovirus shows an association between infection and serious psychiatric disorders". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 79: 152–158. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.026. PMID 30685531.

- ^ Parlog, A.; Schlüter, D.; Dunay, I. R. (March 2015). "Toxoplasma gondii-induced neuronal alterations". Parasite Immunology. 37 (3): 159–70. doi:10.1111/pim.12157. hdl:10033/346575. PMID 25376390. S2CID 17132378.

- ^ Blanchard, N.; Dunay, I. R.; Schlüter, D. (March 2015). "Persistence of Toxoplasma gondii in the central nervous system: a fine-tuned balance between the parasite, the brain and the immune system". Parasite Immunology. 37 (3): 150–58. doi:10.1111/pim.12173. hdl:10033/346515. PMID 25573476. S2CID 1711188.

- ^ Pearce, B. D.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Jones, J. L. (2012). "The Relationship Between Toxoplasma Gondii Infection and Mood Disorders in the Third National Health and Nutrition Survey". Biological Psychiatry. 72 (4): 290–95. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.003. PMC 4750371. PMID 22325983.

- ^ de Barros, J. L.; Barbosa, I. G.; Salem, H.; Rocha, N. P.; Kummer, A.; Okusaga, O. O.; Soares, J. C.; Teixeira; A. L. (February 2017). "Is there any association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 209: 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.016. PMID 27889597.

- ^ Flegr, J.; Lenochová, P.; Hodný, Z.; Vondrová, M (November 2011). "Fatal attraction phenomenon in humans: cat odour attractiveness increased for toxoplasma-infected men, but decreased for infected women". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5 (11): e1389. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001389. PMC 3210761. PMID 22087345.

- ^ Sugden, Karen; Moffitt, Terrie E.; Pinto, Lauriane; Poulton, Richie; Williams, Benjamin S.; Caspi, Avshalom (17 February 2016). "Is Toxoplasma Gondii Infection Related to Brain and Behavior Impairments in Humans? Evidence from a Population-Representative Birth Cohort". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0148435. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1148435S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148435. PMC 4757034. PMID 26886853.

- ^ Amouei, A.; Moosazadeh, M.; Nayeri Chegeni, T.; Sarvi, S.; Mizani, A.; Pourasghar, M.; Hosseini Teshnizi, S.; Hosseininejad, Z.; Dodangeh, S.; Pagheh, A.; Pourmand, A. H.; Daryani, A. (9 April 2020). "Evolutionary puzzle of Toxoplasma gondii with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 67 (5): 1847–1860. doi:10.1111/tbed.13550. PMID 32198980. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Cat parasite linked to mental illness, schizophrenia". CBS. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ "CDC – About Parasites". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Pappas, G.; Roussos, N.; Falagas, M. E. (October 2009). "Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis". International Journal for Parasitology. 39 (12): 1385–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003. PMID 19433092.

- ^ Bigna, Jean Joel; Tochie, Joel Noutakdie; Tounouga, Dahlia Noelle; Bekolo, Anne Olive; Ymele, Nadia S.; Youda, Emilie Lettitia; Sime, Paule Sandra; Nansseu, Jobert Richie (21 July 2020). "Global, regional, and country seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in pregnant women: a systematic review, modelling and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 12102. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012102B. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69078-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7374101. PMID 32694844.