- Beauty Looking Back, Moronobu, late 17th century

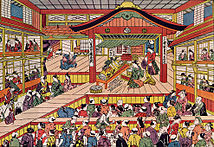

- Shibai Uki-e, Masanobu, c. 1741–1744

- Otani Oniji III, Sharaku, 1794

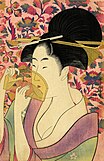

- Comb, Utamaro, 1798

- Hara, 13th station of The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, Hiroshige, 1833–34

- Cuckoo and Azaleas, Hokusai, 1828

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Kuniyoshi, c. 1844

Ukiyo-e[a] is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as 'picture[s] of the floating world'.

In 1603, the city of Edo (Tokyo) became the seat of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. The chōnin class (merchants, craftsmen and workers), positioned at the bottom of the social order, benefited the most from the city's rapid economic growth. They began to indulge in and patronize the entertainment of kabuki theatre, geisha, and courtesans of the pleasure districts. The term ukiyo ('floating world') came to describe this hedonistic lifestyle. Printed or painted ukiyo-e works were popular with the chōnin class, who had become wealthy enough to afford to decorate their homes with them.

The earliest ukiyo-e works emerged in the 1670s, with Hishikawa Moronobu's paintings and monochromatic prints of beautiful women. Colour prints were introduced gradually, and at first were only used for special commissions. By the 1740s, artists such as Okumura Masanobu used multiple woodblocks to print areas of colour. In the 1760s, the success of Suzuki Harunobu's "brocade prints" led to full-colour production becoming standard, with ten or more blocks used to create each print. Some ukiyo-e artists specialized in making paintings, but most works were prints. Artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed the prints; the carver, who cut the woodblocks; the printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto handmade paper; and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works. As printing was done by hand, printers were able to achieve effects impractical with machines, such as the blending or gradation of colours on the printing block.

Specialists have prized the portraits of beauties and actors by masters such as Torii Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku that were created in the late 18th century. The 19th century also saw the continuation of masters of the ukiyo-e tradition, with the creation of Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most well-known works of Japanese art, and Hiroshige's The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Following the deaths of these two masters, and against the technological and social modernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868, ukiyo-e production went into steep decline.

However, in the 20th century there was a revival in Japanese printmaking: the shin-hanga ('new prints') genre capitalized on Western interest in prints of traditional Japanese scenes, and the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement promoted individualist works designed, carved, and printed by a single artist. Prints since the late 20th century have continued in an individualist vein, often made with techniques imported from the West.

Ukiyo-e was central to forming the West's perception of Japanese art in the late 19th century, particularly the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige. From the 1870s onward, Japonisme became a prominent trend and had a strong influence on the early French Impressionists such as Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, as well as influencing Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, and Art Nouveau artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).