| Location | Al-thumama Mesopotamia, Muthanna Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°19′27″N 45°38′14″E / 31.32417°N 45.63722°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 5000 BC |

| Abandoned | c. 700 AD |

| Periods | Uruk period to Early Middle Ages |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1850, 1854, 1902, 1912–1913, 1928–1939, 1953–1978, 2001–2002, 2016–present |

| Archaeologists | William Loftus, Walter Andrae, Julius Jordan, Heinrich Lenzen, Margarete van Ess |

| Official name | Uruk Archaeological City |

| Part of | Ahwar of Southern Iraq |

| Criteria | Mixed: (iii)(v)(ix)(x) |

| Reference | 1481-005 |

| Inscription | 2016 (40th Session) |

| Area | 541 ha (2.09 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 292 ha (1.13 sq mi) |

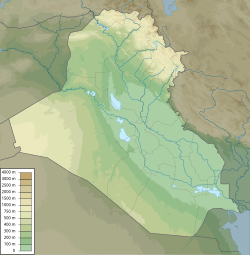

Uruk, known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river. The site lies 93 kilometers (58 miles) northwest of ancient Ur, 108 kilometers (67 miles) southeast of ancient Nippur, and 24 kilometers (15 miles) southeast of ancient Larsa. It is 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.[1]

Uruk is the type site for the Uruk period. Uruk played a leading role in the early urbanization of Sumer in the mid-4th millennium BC. By the final phase of the Uruk period around 3100 BC, the city may have had 40,000 residents,[2] with 80,000–90,000 people living in its environs,[3] making it the largest urban area in the world at the time. King Gilgamesh, according to the chronology presented in the Sumerian King List (SKL), ruled Uruk in the 27th century BC. After the end of the Early Dynastic period, marked by the rise of the Akkadian Empire, the city lost its prime importance. It had periods of florescence during the Isin-Larsa period, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods and throughout the Achaemenid (550–330 BC), Seleucid (312–63 BC) and Parthian (227 BC to AD 224) periods until it was finally abandoned shortly before or after the Islamic conquest of 633–638.

William Kennett Loftus visited the site of Uruk in 1849, identifying it as "Erech", known as "the second city of Nimrod", and led the first excavations from 1850 to 1854.[4]

- ^ Harmansah, 2007

- ^ Nissen, Hans J (2003). "Uruk and the formation of the city". In Aruz, J (ed.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 11–20. ISBN 9780300098839.

- ^ Algaze, Guillermo (2013). "The end of prehistory and the Uruk period". In Crawford, Harriet (ed.). The Sumerian World (PDF). London: Routledge. pp. 68–95. ISBN 9781138238633. Retrieved 26 July 2020.[dead link]

- ^ William Kennett Loftus (1857). Travels and researches in Chaldaea and Susiana: with an account of excavations at Warka, the "Erech" of Nimrod, and Shush, "Shushan the Palace" of Esther, in 1849–52. Robert Carter & Brothers.

Of the primeval cities founded by Nimrod, the son of Gush, four are represented, in Genesis x. 10, as giving origin to the rest : — 'And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Galneh, in the land of Shinar.' ...let us see if there be any site which will correspond with the biblical Erech — the second city of Nimrod. About 120 miles southeast of Babylon, are some enormous piles of mounds, which, from their name and importance, appear at once to justify their claim to consideration. The name of Warka is derivable from Erech without unnecessary contortion. The original Hebrew word 'Erk,' or 'Ark,' is transformed into 'Warka,' either by changing the aleph into vau, or by simply prefixing the vau for the sake of euphony, as is customary in the conversion of Hebrew names to Arabic. If any dependence can be placed upon the derivation of modern from ancient names, this is more worthy of credence than most others of like nature.... Sir Henry Rawlinson states his belief that Warka is Erech, and in this he is supported by concurrent testimony.... [Footnote: See page xvi. of the Twenty-ninth Annual Report of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1852; and Proceedings of the Royal Geogr. Society, vol. i., page 47]