This is a commented version of the Music theory page as it existed on 1 September 2015.

I suggest that the main participants choose a color for their comments: I (Hucbald) chose darkred; Jerome Kohl chose darkviolet. Others may want to choose other colours. This will dispense us from signing each of our comments.

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music.

Christensen (Cambridge History of Wester Theory) quotes from Aristotles' Metaphysics as follows: "In characteristic dialectical fashion, Aristotle contrasted the kind of episteme gained by theoria with the practical knowledge (praktikè) gained through ergon. This was to be a fateful pairing, for henceforth, theory and practice would be dialectically juxtaposed as if joined at the hip. In Aristotle’s conceptual schema, the end of praktike is change in some object, whereas the end of theoria is knowledge of the object itself."

- Are you arguing that practice is not a concern of music theory? Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

I am merely quoting Christensen, I am not (yet) arguing about anything. As Christensen says, Aristotle does contrast theory with practice. This certainly is a point about which we should ponder.

- No doubt there are contrasts to be made, but it seems well established that music theory incorporates both “practices and possibilities.” "Music theory has always maintained its roots in both the mathematical nature of musically organized sound and in performance practice." (Crickmore, "A MUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AKKADIAN TERM sih ̮ puI" don’t see there’s much to ponder about that. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- Are you arguing that practice is not a concern of music theory? Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

It generally derives from observation of how musicians and composers make music, but includes hypothetical speculation. Most commonly, the term describes the academic study and analysis of fundamental elements of music such as pitch, rhythm, harmony, and form, but also refers to descriptions, concepts, or beliefs related to music.

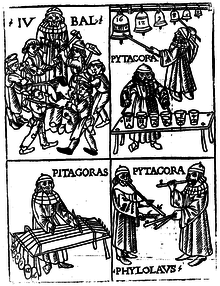

This appears to invert the state of affairs: most commonly, the term refers to descriptions, etc., and in a more specific but more restricted sense to the academic study. Besides, the section on the history of music theory should discuss the changing role of music theory in universities and other such institutions. The section on history should explain that music theory was an important part of the quadrivium, and why; how it was progressively excluded from university teaching in the 17th and 18th century, and how and where it came back to the academic world in the 19th and early 20th century.

- "...should explain that music theory was an important part of the quadrivium, and why; how it was progressively excluded from university teaching in the 17th and 18th century, and how and where it came back to the academic world in the 19th and early 20th century" seems overly detailed for history section. Is the quadrivium a key aspect of the history from an international perspective? Jacques Bailhé 20:25, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Yes, certainly. The position of music theory in the quadrivium certainly deserves at least a short description. It shows that medieval theory retained the specific status that music theory had had in Antiquity, and this is similar, probably to its status in several non European traditions. Or else, we may as well drop everything out.

- I think digressing into the Quadrivium v. the Trivium, the changing role of theory in universities, etc., is, however fascinating, unnecessary detail in an overview of the worldwide history of music theory. The section does mention Boethius and that should be sufficient for the History section. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music (see Definition of music), a more inclusive definition could be that music theory is the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence, as it relates to music.

Doesn't one write "any phenomenon", in this case? And I am not sure that silence can be considered a "sonic phenomenon"... The reason why "silence" is mentioned here appears to be that Definition of music quotes Cage's 4'33. It should be noted, there or here, that actual sound may not necessarily be a condition of music. Busoni considered that music has a written existence before being sounded, and some works are never played (never sounded); yet, they may not be considered "silent".

Yes, the singular "phenomenon" is correct. Due to falling standards of literacy, many English speakers can no longer tell the difference between singular and plural Greek words.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 21:49, 6 September 2015 (UTC)

- The plural is accurately used because the point is that there are many and varied phenomena to be considered. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

"any phenomena"? I think that "any" implies the singular. I trust that "the consideration of many phenomena" would have been more correct.

Aren't rests a type of silence? They're a perfectly legitimate topic of music theory. Actually, "phenomena" would be usable in this sentence (imagine substituting a more familiar plural such as "events"), but the word doesn't agree with "it" in the following clause; "they" would work. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:11, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Wahoofive - Right you are. Good solution. Thanks. Jacques Bailhé 06:15, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

- Cage's 4'33" is not silent. The piece "organizes" ambient sound and asks us to consider whether the imposition of an organizing structure then transforms unorganized sound into music. Jacques Bailhé 20:25, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

The point is not whether or not 4'33 is silent, but whether it is relevant to music theory. The work certainly does not "organize" the ambient sound, it merely tries (not so successfully, I think) to draw attention to it. One may argue that 4'33 has theoretical implications, but these should be described and discussed (with references!). I was merely arguing that the original article, when it mentioned silence without quoting anything specific, may have done so because another article (Definition of music) mentioned 4'33.

- Discussion and references about Cage’s 4’33” are not in the History section or the Music theory article, but in the article on that work and in Definition of Music. Don’t see the point of discussing it further here. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

If the plural form is accepted, should it not then read "all phenomena"? Of course, silence is a legitimate concern of theory, but this runs up against a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory, without actually addressing the question of the theory of that aspect. If we allow this kind of thinking, then this article had better be expanded by several orders of magnitude, rather than being reined in to a manageable size.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 04:46, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- "a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory." This is not a problem, but a necessarily wide point of view. As we know from studies of world musics, our Western view of what is music, and therefore what aspects constiThistute music, needs to allow for the wide ranging concepts around the world of what music is. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

This article is not about the widely different definitions of "music" around the world, but about theory. The purpose of the article is not to produce theories about any kind of music, but to describe existing ones.

- The “widely different definitions of “music” around the world” are a critical aspect of music theory viewed in an international context. As you pointed out earlier, coming to grips with a workable definition of music—problematic as that may be—is fundamental to understanding what theory is talking about. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- "a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory." This is not a problem, but a necessarily wide point of view. As we know from studies of world musics, our Western view of what is music, and therefore what aspects constiThistute music, needs to allow for the wide ranging concepts around the world of what music is. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Music theory is a subfield of musicology, which is itself a subfield within the overarching field of the arts and humanities.

These "fields" need definition. Are they institutional fields in American universities, or domains of research, etc.

- They are defined in their own articles. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Or course. This was not my point. Rather, I question the hierarchy of subfields, which certainly is not endorsed by their own articles.

- Arts and Humanities contains the field of Musicology which contains Music Theory--right? That the sentence is talking about academic fields of study in general seems plain enough. IN Europe, they hold an annual European Conference on Arts & Humanities. If there are any differences in this hierarchy or division of fields between the U.S. and other countries' systems, do we need to explicate in this article? Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- They are defined in their own articles. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Actually, I think the statement is insupportable. From an historical point of view, music theory has been around since Ancient Greece, whereas the discipline of musicology is a creation of the late 19th century. Your question, Hucbald, is a good one, but supposes a framework of the present-day academy, without considering a broader historical view. On the other hand, all that is neede to cement this statement is a reliable source.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 04:58, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Jerome, WP's article on musicology (linked in the sentence in question) reads "Musicology also has two central, practically oriented subdisciplines with no parent discipline: performance practice and research (sometimes viewed as a form of artistic research), and the theory, analysis and composition of music." That sentence comes from the Musicology article lead. The article's section "Subdisciplines" explains further. If the sentence from the Music Theory article needs a different reference, let me know. Jacques Bailhé 06:26, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

- Music theory was not invented in Ancient Greece--as the History section makes clear. Similarly, the statement that "musicology is a creation of the late 19th century" is contradicted by innumerable writings on the subject in a wide variety of previous times and cultures. Again, see the History section. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC

The article claims indeed that music theory predates written theory, a highly questionable point of view. "Musicology" certainly is a creation of the late 19th century, as is widely documented. It may have precedents, especially in the 18th century, but it would be a derision to call anything and everything "musicology". I am most curious to read more about those "innumerable writings" in "a wide variety of previous times and cultures". Can you provide one or two examples?

- The History section in the Music Theory article provides a number references that refer to what is commonly understood to be the process by which “orality” naturally precedes written documentation. But as previously mentioned on this talk page, Taruskin’s The Oxford History of Western Music, Vol. 1 opening chapter, offers a discussion of this in regard to Western music. Have a look at some of the papers at www. http://journal.oraltradition.org. Elsewhere, Sam Mirleman tells us “the Mesopotamian music texts are examples of what might be called “orality in written form”. It is well known that many cultures transmit knowledge (including musical knowledge) in an essentially oral form, which may be supplemented by writing. Certainly, this is the case with notation in its use almost everywhere, even in Europe. Indeed, it has been convincingly argued that Western Medieval musical culture relied to a great degree on oral transmission, despite the use of notation and written treatises. Similarly, in cultures such as ancient India and China, notation and theoretical writings survive, but any attempt to reconstruct and decipher these materials must be tempered by the knowledge that they originated in a musical culture in which notation was not intended to be understood by those who are uninitiated in the oral tradition. Similarly, the culture of ancient Mesopotamia was one in which orality certainly played an important role, despite our knowledge of tens of thousands of texts.” (“Tuning Procedures in Ancient Iraq.” p. 5. AAWM 2012 lecture) From the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Foundations site (www. http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home.html)

“Ultimately, the divide between oral and written history is a misconception. Writing and orality do not exclude each other; rather they are complementary. Each method has strengths that depend largely on the situations in which it is used. They show similarities as well. As Stó:lō historian Naxaxahtls’i (Albert “Sonny” McHalsie) puts it, “The academic world and the oral history process both share an important common principle: They contribute to knowledge by building upon what is known and remembering that learning is a lifelong quest."3 Together oral and written methods of recalling and recounting the past have the potential to contribute greatly to the historical record. Since the mid20th century, particularly as a result of growing interest in the histories of marginalized groups such as African Americans, women, and the working class, Western academic discourse has increasingly accepted oral history as a legitimate and valuable addition to the historical record.4” 3. Albert “Sonny” McHalsie (Naxaxalht’i), “We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us,” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce Granville Miller (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 82. 4. Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, eds., The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 1998), ix–xiii. Jacques Bailhé 16:35, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

Etymologically, music theory is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek θεωρία, a looking at, viewing, contemplation, speculation, theory, also a sight, a spectacle.[1] As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonance, and rhythmic relationships, but there is also a body of theory concerning such practical aspects as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production.[2]

Palisca and Bent more precisely write: "Theory is now understood as principally the study of the structure of music. This can be divided into melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony and form, but these elements are difficult to distinguish from each other and to separate from their contexts. At a more fundamental level theory includes considerations of tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions and the acoustics of pitch systems. A body of theory exists also about other aspects of music, such as composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation and electronic sound production."

- "principally the study of the structure of music" overemphasizes structure in relation to other aspects like melody and rhythm. "'...music theory' is an act of contemplation of music....'" is more accurate. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Would you doubt that "structure" involves melody and rhythm? If so, we are not speaking of the same thigs.

- Structure certainly involves aspects like rhythm and melody—although not necessarily those two aspects. My point is that Palisca/Bent open their definition of music theory with a statement that I think is unsupportable and unintentionally misleading: “Theory is now understood as principally the study of the structure of music.” Music theory is not necessarily “study,” but rather and specifically “theorizing” about music, in whatever form that may take, be it published paper, basic harmonic analysis, a critic’s appraisal of why a piece or performance was effective or not, etc. “Structure” is one of many aspects contemplated by theory. Limiting theory to “study” (implying formal academic work) and “structure” unnecessarily and unjustifiably restricts theory. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- "principally the study of the structure of music" overemphasizes structure in relation to other aspects like melody and rhythm. "'...music theory' is an act of contemplation of music....'" is more accurate. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

This is in the lead of the NG article, not in "1. Definitions" which does not exist: after the lead, the article continues with 1. Introduction (Palisca), noting the absence of overlap between four treatises; 2. Definitions (Palisca) describing a possible mapping of the field, inspired by that of Aristides Quitilianus, but a triffle too abstract to serve as an outline for the WP article.

A person who researches, teaches, or writes articles about music theory is a music theorist. University study, typically to the M.A. or Ph.D level, is required to teach as a tenure-track music theorist in an American or Canadian university.

Does this really belong here?

- No. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Which part, Wahoofive? If you mean the second sentence, I agree with you; the first sentence seems unassailable.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 05:01, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Both parts. The first sentence is just a dictionary entry, not necessary for understanding music theory. —Wahoofive (talk) 15:38, 9 September 2015 (UTC)

- No. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and, especially, analysis enabled by Western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used.

If musical analysis is meant here, there is a specific article; this here says either too much or not enough. First of all, one should explain the relation between music theory and music analysis. Then, why should mathematics come first? What about figuring (which is not really "graphic")? Why "enabled by Western music notation"? – notation does not "enable" analysis, it is part of it. And this fails to recognize that musical analysis may be a discipline in itself, not necessarily making use of "other [borrowed] methods".

The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory may be found in oral and practical music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from Mesopotamia, China,[3] and prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and, potentially, something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers (see History of music and Musical instrument).

The article History of music does not say a single word about the origin of theory. It says "The prehistoric is considered to have ended with the development of writing, and with it, by definition, prehistoric music." The word "theory" appears only once in the whole article: "...the sonata, the symphony, and the concerto, though none of these were specifically defined or taught at the time as they are now in music theory."

- Don't understand what bearing that has on an article about Music Theory and its history. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

The article Musical instrument never uses the word "theory".

- Musical instrument is in the lead to the article, not the History section and is there to point readers to Wikipedia’s discussion of the practical and conceptual aspects of instruments. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are clearly visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music making. Many cultures, at least as far back as ancient Mesopotamia, Pharoanic Egypt, and ancient China have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation.

This, which already has been much discussed, remains unacceptable. One might allow oneself to suspect the existence of a theory in oral and practical traditions, but certainly not observe there its "development, preservation and transmission". See also below.

- Music theory is not "suspected" to exist in oral and practical traditions. It inherently must. For an excellent discussion oral v. written, see Taruskin's opening chapter to “The Oxford History of Western Music” in Vol 1., “Music from the Earliest notations to the Sixteenth Century.” Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Taruskin discusses oral transmission, but never even hints at the idea of an "oral theory". Or do we not have the same version of the book?

- Taruskin writes, “…the early chapters are dominated by the interplay of literate and preliterate modes of thinking and transmission….” Modes of thinking = theory. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- I think this, and the next section, were added in a desperate attempt to make the article less ethnocentric on Western music. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

This is an important remark, Wahoofive, and I wouldn't like to appear to reject it. The fact is that Music Theory itself might well be (to a large extent) a characteristic of Western musical culture. A traditional culture, being less aware of its own history (or minding less) may be less prone to distanciate itself from its own practices and usages. There is nothing "etnocentric" to believe (as I tend to do) that Music Theory is characteristic of the West. Attempting to make the article less ethnocentric actually resulted in stretching the very definition of Music Theory outside its own limits. — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 20:01, 9 September 2015 (UTC)

- The comment unabashedly announces a clear bias that I believe is unjustifiably limiting to thinking about music theory and its history and has no basis in historical fact, as the History section makes clear. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Jacques, I (and my students) have done a lot of work on non European theories. The corpus of Arabic theories, for instance, is minimal when compared to the Western one, even if one includes the most recent discoveries, about which published references ain't yet available. This is not a bias, it is a fact – a fact which certainly deserves some discussion in the article. The present section on "history of theory" makes nothing of this clear.

- I don’t understand why “The corpus of Arabic theories, for instance, is minimal when compared to the Western one,” is relevant to the History section, which only sets out a brief record of development and makes no value judgments. You write, “A traditional culture, being less aware of its own history (or minding less) may be less prone to distanciate itself from its own practices and usages. There is nothing "etnocentric"[sic] to believe (as I tend to do) that Music Theory is characteristic of the West.” Perhaps I misunderstand your point, but having read that a couple times now, it seems to contain bias against the sophistication of “traditional culture” and appears to want to put Western theory at the top of the heap. I imagine Western theory may well outweigh others in terms of sheer poundage, but as with your comment about the relative value of Arabic theory being somehow dependent on its size, I just don’t see that any such weighing is appropriate or useful. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- The comment unabashedly announces a clear bias that I believe is unjustifiably limiting to thinking about music theory and its history and has no basis in historical fact, as the History section makes clear. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- Music theory is not "suspected" to exist in oral and practical traditions. It inherently must. For an excellent discussion oral v. written, see Taruskin's opening chapter to “The Oxford History of Western Music” in Vol 1., “Music from the Earliest notations to the Sixteenth Century.” Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- ^ OED 2005.

- ^ Palisca and Bent n.d., Theory, theorists. 1. Definitions.

- ^ Latham 2002, 15–17.