| Vasishthiputra Pulumavi | |

|---|---|

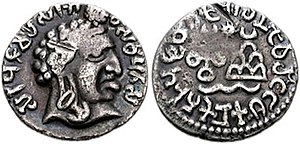

Bilingual coinage of Sri Vasishthiputra Pulumavi in Prakrit and Dravidian, and transcription of the obverse Prakrit legend. Obverse: Portrait of the king. Legend in Prakrit in the Brahmi script (starting at 12 o'clock): 𑀭𑀜𑁄 𑀯𑀸𑀲𑀺𑀣𑀺𑀧𑀼𑀢𑀲 𑀲𑀺𑀭𑀺 𑀧𑀼𑀎𑀼𑀫𑀸𑀯𑀺𑀲 Raño Vāsiṭhiputasa Siri-Puḷumāvisa "Of King Lord Pulumavi, son of Vasishthi" Reverse: Ujjain and arched-hill symbols. Legend in Dravidian (close to Telugu and Tamil),[1] and the Dravidian script,[1] similar to the Brahmi script[2] (starting at 12 o'clock): 𑀅𑀭𑀳𑀡𑀓𑀼 𑀯𑀸𑀳𑀺𑀣𑀺 𑀫𑀸𑀓𑀡𑀓𑀼 𑀢𑀺𑀭𑀼 𑀧𑀼𑀮𑀼𑀫𑀸𑀯𑀺𑀓𑀼 Arahaṇaku Vāhitti Mākaṇaku Tiru Pulumāviku[3] or: Aracanaku Vācitti Makaṇaku Tiru Pulumāviku[4] "Of King Tiru Pulumavi, son of Vasishthi"[2] | |

| Satavahana King | |

| Reign | c. 85–125 CE |

| Predecessor | Gautamiputra Satakarni |

| Successor | Vashishtiputra Satakarni |

| Dynasty | Satavahana |

| Father | Gautamiputra Satakarni |

| Religion | Buddhism |

Vasishthiputra Pulumavi (Brahmi: 𑀯𑀸𑀲𑀺𑀣𑀺𑀧𑀼𑀢 𑀧𑀼𑀎𑀼𑀫𑀸𑀯𑀺, Vāsiṭhiputa Puḷumāvi, IAST: Vāsiṣṭhiputra Śrī Pulumāvi) was a Satavahana king, and the son of Gautamiputra Satakarni.[5] The new consensus for his reign is c. 85-125 CE,[6][7][8] although it was earlier dated variously: 110–138 CE[9] or 130–159 CE.[10] He is also referred to as Vasishthiputra Sri Pulumavi. Ptolemy, the second century writer, refers to Pulumavi as Siriptolemaios, a contemporary of the Western satrap, Chastana.[11]

He is said to be the first Satavahana king to rule from Dhanyakataka, now Dharanikota in Andhra Pradesh,[12] while some note his capital as Paithan.[13]

- ^ a b Sircar, D. C. (2008). Studies in Indian Coins. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 9788120829732.

- ^ a b "The Sātavāhana issues are uniscriptural, Brahmi but bilingual, Prākrit and Telugu." in Epigraphia Andhrica. 1975. p. x.

- ^ Epigraphia Āndhrica. Government of Andhra Pradesh. 1969. p. XV.

- ^ Nākacāmi, Irāmaccantiran̲; Nagaswamy, R. (1981). Tamil Coins: A Study. Institute of Epigraphy, Tamilnadu State Department of Archaeology. p. 132.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 381. ISBN 9788131711200. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ Bhandare, Shailendra, (1999). Historical Analysis of the Satavahana Era: A study of Coins, University of Mumbai, pp. 168-178.

- ^ Shimada, Akira, (2012). Early Buddhist Architecture in Context: The Great Stupa at Amaravati (ca 300 BCE - 300 CE), Brill, p. 52.

- ^ von Hinuber, Oskar, (2016). "Buddhist Texts and Buddhist Images: New Evidence from Kanaganahalli (Karnataka/India)", ARIRIAB Vol. XIX (March 2016), p. 15.

- ^ Carla M. Sinopoli (2001). "On the edge of empire: form and substance in the Satavahana dynasty". In Susan E. Alcock (ed.). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–168. ISBN 9780521770200.

- ^ Susan L. Huntington (1 January 1984). The "Pāla-Sena" Schools of Sculpture. Brill Archive. p. 175. ISBN 90-04-06856-2.

- ^ "According to Ptolemy, Siriptolemaios (Sri Pulumayi), son of Gautamiputra Satakarni, continued to reign at Paithan (Pratisthana), while Ozene (Ujjain) fell into the hands of Tiasthenes (Chastana)." Alain Danielou, A Brief History of India (Inner Traditions, 2003), mentioned here

- ^ H. Sarkar; S. P. Nainar (2007). Amaravati (5th ed.). Archaeological Survey of India. p. 8.

- ^ Alcock, Susan E.; Alcock, John H. D'Arms Collegiate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Classics and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Susan E.; D'Altroy, Terence N.; Morrison, Kathleen D.; Sinopoli, Carla M. (2001). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780521770200.