This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (May 2020) |

| Venezuelan Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Castellano venezolano | |

| Pronunciation | [kasteˈʝano βenesoˈlano] |

| Native to | Venezuela |

Native speakers | 29,794,000 in Venezuela, all users (2014)[1] L1 users: 29,100,000 (2013) L2 users: 694,000 (2013) |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | Amazonian Llanero Andino Western Eastern Isleño[citation needed] Costeño Zuliano/Maracucho Central Oriental Trinidadian |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academia Venezolana de la Lengua |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-2 | spa[2] |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | es-VE |

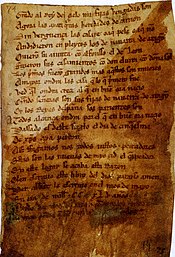

Kinds of Spanish spoken in Venezuela. | |

Venezuelan Spanish (castellano venezolano or español venezolano) refers to the Spanish spoken in Venezuela.

Spanish was introduced in Venezuela by colonists. Most of them were from Galicia, Basque Country, Andalusia, or the Canary Islands.[3] The last has been the most fundamental influence on modern Venezuelan Spanish, and Canarian and Venezuelan accents may even be indistinguishable to other Spanish-speakers.

Italian and Portuguese immigrants from the late 19th and the early 20th century have also had an influence; they influenced vocabulary and its accent, given its slight sing-songy intonation, like Rioplatense Spanish. German settlers also left an influence when Venezuela was contracted as a concession by the King of Spain to the German Welser banking family (Klein-Venedig, 1528–1546).

The Spaniards additionally brought African slaves, which is the origin of expressions such as chévere ("excellent"), which comes from Yoruba ché egberi. Other non-Romance words came from indigenous languages, such as guayoyo (a type of coffee) and caraota (black bean).

- ^ Spanish → Venezuela at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- ^ "ISO 639-2 Language Code search". Library of Congress. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Ostler, Nicholas (2010). Empires of the word : a language history of the world. Folio Society. pp. 335–347. OCLC 692307052.