| |

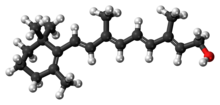

Retinol

Retinal plays a biological role in vision, but most of the effects of vitamin A are exerted by retinoic acid, which binds to nuclear receptors and regulates gene transcription. | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular[1] |

| Drug class | Vitamin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.195 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H30O |

| Molar mass | 286.459 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 62–64 °C (144–147 °F) |

| Boiling point | 137–138 °C (279–280 °F) (10−6 mm Hg) |

| |

| |

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that is an essential nutrient. The term "vitamin A" encompasses a group of chemically related organic compounds that includes retinol, retinyl esters, and several provitamin (precursor) carotenoids, most notably β-carotene (beta-carotene).[3][4][5][6] Vitamin A has multiple functions: growth during embryo development, maintaining the immune system, and healthy vision. For aiding vision specifically, it combines with the protein opsin to form rhodopsin, the light-absorbing molecule necessary for both low-light (scotopic vision) and color vision.[7]

Vitamin A occurs as two principal forms in foods: A) retinoids, found in animal-sourced foods, either as retinol or bound to a fatty acid to become a retinyl ester, and B) the carotenoids α-carotene (alpha-carotene), β-carotene, γ-carotene (gamma-carotene), and the xanthophyll beta-cryptoxanthin (all of which contain β-ionone rings) that function as provitamin A in herbivore and omnivore animals which possess the enzymes that cleave and convert provitamin carotenoids to retinol.[8] Some carnivore species lack this enzyme. The other carotenoids do not have retinoid activity.[6]

Dietary retinol is absorbed from the digestive tract via passive diffusion. Unlike retinol, β-carotene is taken up by enterocytes by the membrane transporter protein scavenger receptor B1 (SCARB1), which is upregulated in times of vitamin A deficiency (VAD).[6] Retinol is stored in lipid droplets in the liver. A high capacity for long-term storage of retinol means that well-nourished humans can go months on a vitamin A-deficient diet, while maintaining blood levels in the normal range.[4] Only when the liver stores are nearly depleted will signs and symptoms of deficiency show.[4] Retinol is reversibly converted to retinal, then irreversibly to retinoic acid, which activates hundreds of genes.[9]

VAD is common in developing countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Deficiency can occur at any age but is most common in pre-school age children and pregnant women, the latter due to a need to transfer retinol to the fetus. VAD is estimated to affect approximately one-third of children under the age of five around the world, resulting in hundreds of thousands of cases of blindness and deaths from childhood diseases because of immune system failure.[10] Reversible night blindness is an early indicator of low vitamin A status. Plasma retinol is used as a biomarker to confirm VAD. Breast milk retinol can indicate a deficiency in nursing mothers. Neither of these measures indicates the status of liver reserves.[6]

The European Union and various countries have set recommendations for dietary intake, and upper limits for safe intake. Vitamin A toxicity also referred to as hypervitaminosis A, occurs when there is too much vitamin A accumulating in the body. Symptoms may include nervous system effects, liver abnormalities, fatigue, muscle weakness, bone and skin changes, and others. The adverse effects of both acute and chronic toxicity are reversed after consumption of high dose supplements is stopped.[6]

- ^ "Vitamin A". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Aquasol A - vitamin a palmitate injection, solution". DailyMed. 14 August 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Vitamin A Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. March 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Vitamin A". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

DRI VitAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Blaner WS (2020). "Vitamin A". In Marriott BP, Birt DF, Stallings VA, Yates AA (eds.). Present Knowledge in Nutrition (Eleventh ed.). London: Academic Press (Elsevier). pp. 73–92. ISBN 978-0-323-66162-1.

- ^ Wolf G (June 2001). "The discovery of the visual function of vitamin A". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (6): 1647–1650. doi:10.1093/jn/131.6.1647. PMID 11385047.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Wu2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kedish2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

UNICEFvitaminAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).