| Vitamin B3 | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

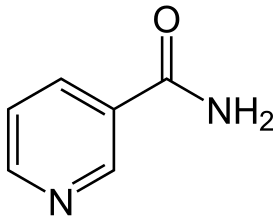

Structure of nicotinamide, one of the vitamers of vitamin B3 | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Vitamin B3 deficiency |

| ATC code | A11H |

| Biological target | enzyme cofactor |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Niacin |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D009536 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Vitamin B3, colloquially referred to as niacin, is a vitamin family that includes three forms, or vitamers: niacin (nicotinic acid), nicotinamide (niacinamide), and nicotinamide riboside.[1] All three forms of vitamin B3 are converted within the body to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD).[1] NAD is required for human life and people are unable to make it within their bodies without either vitamin B3 or tryptophan.[1] Nicotinamide riboside was identified as a form of vitamin B3 in 2004.[2][1]

Niacin (the nutrient) can be manufactured by plants and animals from the amino acid tryptophan.[3] Niacin is obtained in the diet from a variety of whole and processed foods, with highest contents in fortified packaged foods, meat, poultry, red fish such as tuna and salmon, lesser amounts in nuts, legumes and seeds.[4][5] Niacin as a dietary supplement is used to treat pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency. Signs and symptoms of pellagra include skin and mouth lesions, anemia, headaches, and tiredness.[6] Many countries mandate its addition to wheat flour or other food grains, thereby reducing the risk of pellagra.[4][7]

The amide nicotinamide (niacinamide) is a component of the coenzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+). Although niacin and nicotinamide are identical in their vitamin activity, nicotinamide does not have the same pharmacological, lipid-modifying effects or side effects as niacin, i.e., when niacin takes on the -amide group, it does not reduce cholesterol nor cause flushing.[8][9] Nicotinamide is recommended as a treatment for niacin deficiency because it can be administered in remedial amounts without causing the flushing, considered an adverse effect.[10] In the past, the group was loosely referred to as vitamin B3 complex.[11]

- ^ a b c d Stipanuk MH, Caudill MA (2013). Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 541. ISBN 9780323266956.

Vitamin B3... potentially includes three different molecular forms: nicotinic acid, niacinamide, and nicotinamide riboside

- ^ Bieganowski P, Brenner C (May 14, 2004). "Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans". Cell. 117 (4): 495–502. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00416-7. PMID 15137942.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

DRItextwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Niacin". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. October 8, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ "Niacin Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Hegyi J, Schwartz RA, Hegyi V (January 2004). "Pellagra: dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea". International Journal of Dermatology. 43 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01959.x. PMID 14693013. S2CID 33877664.

- ^ "Why fortify?". Food Fortification Initiative. 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Jaconello P (October 1992). "Niacin versus niacinamide". CMAJ. 147 (7): 990. PMC 1336277. PMID 1393911.

- ^ Kirkland JB (May 2012). "Niacin requirements for genomic stability". Mutation Research. 733 (1–2): 14–20. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.008. PMID 22138132.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Pellagra And Its Preventionwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Silvestre R, Torrado E (2018). Metabolic Interaction in Infection. Springer. p. 364. ISBN 9783319749327.

Niacin or nicotinate, together with its amide form nicotinamide, defines the group of vitamin B3 complex