This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2010) |

The voltaic pile was the first electrical battery that could continuously provide an electric current to a circuit.[1] It was invented by Italian chemist Alessandro Volta, who published his experiments in 1799.[2] Its invention can be traced back to an argument between Volta and Luigi Galvani, Volta's fellow Italian scientist who had conducted experiments on frogs' legs.[3] Use of the voltaic pile enabled a rapid series of other discoveries, including the electrical decomposition (electrolysis) of water into oxygen and hydrogen by William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle (1800), and the discovery or isolation of the chemical elements sodium (1807), potassium (1807), calcium (1808), boron (1808), barium (1808), strontium (1808), and magnesium (1808) by Humphry Davy.[4][5]

The entire 19th-century electrical industry was powered by batteries related to Volta's (e.g. the Daniell cell and Grove cell) until the advent of the dynamo (the electrical generator) in the 1870s.[6]

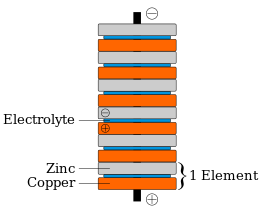

Volta's invention was built on Luigi Galvani's 1780s discovery that a circuit of two metals and a frog's leg can cause the frog's leg to respond.[1] Volta demonstrated in 1794 that when two metals and brine-soaked cloth or cardboard are arranged in a circuit they too produce an electric current. In 1800, Volta stacked several pairs of alternating copper (or silver) and zinc discs (electrodes) separated by cloth or cardboard soaked in brine, which increased the total electromotive force.[7] When the top and bottom contacts were connected by a wire, an electric current flowed through the voltaic pile and the connecting wire. The voltaic pile, together with many scientific instruments that belonged to Alessandro Volta, are preserved in the University History Museum of the University of Pavia, where Volta taught from 1778 to 1819.[8]

- ^ a b "Battery: Voltaic Pile". americanhistory.si.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-12.

- ^ "Alessandro Volta | Biography, Facts, Battery, & Invention | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-04-15. Retrieved 2024-05-12.

- ^ "The Voltaic Pile | Distinctive Collections Spotlights". libraries.mit.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Deckerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Russell, Colin (August 2003). "Enterprise and electrolysis..." Chemistry World.

- ^ "Alessandro Volta | Biography, Facts, Battery, & Invention | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-04-15. Retrieved 2024-05-12.

- ^ Mottelay, Paul Fleury (2008). Bibliographical History of Electricity and Magnetism (Reprint of 1892 ed.). Read Books. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-4437-2844-7.

- ^ "Sala Volta". Musei Unipv. Retrieved 21 August 2022.