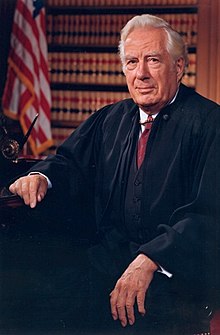

Warren E. Burger | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1986 | |

| 15th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office June 23, 1969 – September 26, 1986 | |

| Nominated by | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Earl Warren |

| Succeeded by | William Rehnquist |

| 20th Chancellor of the College of William & Mary | |

| In office June 26, 1986 – July 1, 1993 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Alvin Duke Chandler (1974) |

| Succeeded by | Margaret Thatcher |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office March 29, 1956 – June 23, 1969 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Harold Montelle Stephens |

| Succeeded by | Malcolm Richard Wilkey |

| 11th United States Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division | |

| In office May 1, 1953 – April 14, 1956 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Holmes Baldridge |

| Succeeded by | George Cochran Doub |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Warren Earl Burger September 17, 1907 Saint Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 1995 (aged 87) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Elvera Stromberg

(m. 1933; died 1994) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | St. Paul College of Law (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul College of Law in 1931. He helped secure the Minnesota delegation's support for Dwight D. Eisenhower at the 1952 Republican National Convention. After Eisenhower won the 1952 presidential election, he appointed Burger to the position of Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Division. In 1956, Eisenhower appointed Burger to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Burger served on this court until 1969 and became known as a critic of the Warren Court.

In 1969, President Richard Nixon nominated Burger to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice, and Burger won Senate confirmation with little opposition. He did not emerge as a strong intellectual force on the Court, but sought to improve the administration of the federal judiciary. He also helped establish the National Center for State Courts and the Supreme Court Historical Society. Burger remained on the Court until his retirement in 1986, when he became Chairman of the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. He was succeeded as Chief Justice by William H. Rehnquist, who had served as an associate justice since 1972.

In 1974, Burger wrote for a unanimous court in United States v. Nixon, which rejected Nixon's invocation of executive privilege in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The ruling played a major role in Nixon's resignation. Burger joined the majority in Roe v. Wade in holding that the right to privacy prohibited states from banning abortions. Later analyses have suggested that Burger joined the majority in Roe solely to prevent Justice William O. Douglas from controlling assignment of the opinion.[1] On the contrary, Burger would vote with the majority in Harris v. McRae in 1980, which formally launched the Hyde Amendment into effect. He later abandoned Roe v. Wade in Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. His majority opinion in INS v. Chadha struck down the one-house legislative veto.

Although Burger was nominated by a conservative president,[2] the Burger Court also delivered some of the most liberal decisions regarding abortion, capital punishment, religious establishment, sex discrimination, and school desegregation[3] during his tenure.[4]

- ^ Woodward, Bob; Armstrong, Scott (May 31, 2011). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1439126349. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Perceived Qualifications and Ideology of Supreme Court Nominees, 1937–2012" (PDF). SUNY at Stony Brook. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Barker, Lucius J. (Autumn 1973). "Black Americans and the Burger Court: Implications for the Political System". Washington University Law Review. 1973 (4): 747–777. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Washington University Law Review Archive.

- ^ Earl M. Maltz, The Coming of the Nixon Court: The 1972 Term and the Transformation of Constitutional Law (University Press of Kansas; 2016)