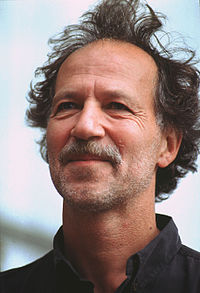

Werner Herzog (born 1942)[1] is a German filmmaker whose films often feature ambitious or deranged protagonists with impossible dreams.[2][3] Herzog's works span myriad genres and mediums, but he is particularly well known for his documentary films, which he typically narrates.[4]

In 1962, Herzog made his directorial debut with the German-language short Herakles. His feature film debut—Signs of Life (1968)—garnered him the Silver Bear at Berlinale.[5] Six years later, Herzog's The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival.[6] Starting in this period, Herzog collaborated with actor Klaus Kinski on five films, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Woyzeck (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982), and Cobra Verde (1987).[2] Fitzcarraldo won Herzog the Best Director Award at Cannes.[7] His tumultuous relationship with Kinski was the subject of Herzog's 1999 documentary My Best Fiend.[8] Herzog directed two films in 2009, My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done and the Nicolas Cage-starring Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans,[9] both of which were nominated for a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.[10] He has directed a number of other fictional feature films as well as shorts.

Herzog made his documentorial debut with 1969's The Flying Doctors of East Africa. In his documentaries, Herzog often explores the "moral or existential abyss", commonly in nature.[11] His first documentary to screen at Cannes, Fata Morgana (1971), for instance, pairs footage of barren African desert landscapes with a recitation of the Mayan creation myth, the Popol Vuh.[12][13] Similarly, Herzog's film Lessons of Darkness (1992) matches Richard Wagner overtures with documentation of the Gulf War's wake of chaos and destruction in Kuwait.[14][15] Lessons of Darkness was criticized for its supposed "aestheticizing" of war.[16] As with his fictional works, Herzog's documentaries also examine nonconformists outside conventional society,[17] such as Timothy Treadwell in his 2005 documentary Grizzly Man.[17][18] Herzog studied the pilot Dieter Dengler in his 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly, which he later remade into the 2006 feature film Rescue Dawn starring Christian Bale.[11] The following year, his exploration of the lives of scientists in Antarctica—2007's Encounters at the End of the World—garnered him an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary.[19][20] For his 2018 documentary Meeting Gorbachev, Herzog had extensive interviews with the Soviet leader.[21] He has directed dozens of other documentaries, including shorts and television segments.

In addition to his own works, Herzog has appeared in other projects, including as the narrator or subject of documentaries and mockumentaries. He has appeared in two Les Blank documentaries, including Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980), in which he eats his shoe after losing a bet to then-college student Errol Morris,[22] and Burden of Dreams, shot during and about the chaotic filming of Herzog's Fitzcarraldo.[23] Herzog has also appeared in commercial films and television series, often portraying villains,[24] such as in the 2012 Tom Cruise film Jack Reacher,[25] or, in 2019, The Mandalorian.[26] He has made cameo appearances in The Simpsons, Parks and Recreation, and other television series.

- ^ O'Mahoney, John (29 March 2002). "The enigma of Werner H". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b "40 Great Actor & Director Partnerships: Klaus Kinski & Werner Herzog". Empire. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 July 2008). "Herzog and the forms of madness". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Beasley, Tom (19 June 2020). "Werner Herzog says his famous accent is 'in some ways a stage voice'". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Signs of Life". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

engimawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Fitzcarraldo". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

fiendwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

nolawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Addiego, Walter (13 November 2009). "Werner Herzog tickles a delirious funny bone". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b Newton, Michael (1 June 2013). "Werner Herzog: 50 years of potent, inspiring, disturbing films". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Prager, Brad (2007). The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth. Wallflower Press. pp. 174–179. ISBN 9781905674176.

- ^ "Fata Morgana". MUBI. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Lessons of Darkness". International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (25 October 1995). "Film Review; Werner Herzog's Vision Of a World Gone Amok". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Weber, Eva (2 October 2010). "Werner Herzog's 'Lessons of Darkness'". International Documentary Association. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b Kellaway, Kate (7 August 2022). "Werner Herzog: 'I was never, contrary to rumours, a hazard-seeking, crazy stuntman'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

bearwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

coldwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morfoot, Addie (3 December 2008). "Encounters at the End of the World". Variety. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gorbywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Abramovitch, Seth (5 February 2015). "1979: When Werner Herzog Ate His Shoe". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1 January 1982). "Burden of Dreams". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (19 June 2020). "Werner Herzog: 'I'm fascinated by trash TV. The poet must not avert his eyes'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

reacherwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

mandowas invoked but never defined (see the help page).