William Cullen | |

|---|---|

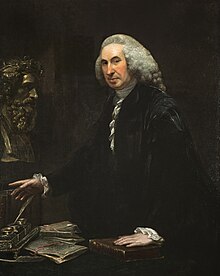

Portrait by David Martin, 1776 | |

| Born | 15 April 1710 |

| Died | 5 February 1790 (aged 79) |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Notable students | |

William Cullen FRS FRSE FRCPE (/ˈkʌlən/; 15 April 1710 – 5 February 1790) was a Scottish physician, chemist and agriculturalist, and professor at the Edinburgh Medical School.[3] Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment: He was David Hume's physician, and was friends with Joseph Black, Henry Home, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and Adam Smith, among others.

He was president of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (1746–47), president of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1773–1775) and first physician to the king in Scotland (1773–1790).[4] He also assisted in obtaining a royal charter for the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, resulting in the formation of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783.[5]

Cullen was a beloved teacher, and many of his students became influential figures. He kept in contact with many of his students, including Benjamin Rush, a central figure in the founding of the United States of America; John Morgan, who founded the first medical school in the American colonies, the Medical School at the College of Philadelphia;[6] William Withering, the discoverer of digitalis; Sir Gilbert Blane, medical reformer of the Royal Navy; and John Coakley Lettsom, the philanthropist and founder of the Medical Society of London.[7]

Cullen's student and later rival John Brown developed the medical system known as Brunonianism, which conflicted with Cullen's. The competition between the two systems had knock-on effects in how patients were treated worldwide, especially in Italy and Germany, during the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century.[8]

Cullen was also an author. He published a number of medical textbooks, mostly for the use of his students, though they were popular in Europe and the American colonies. His best known work was First Lines of the Practice of Physic, which was published in a series of editions between 1777 and 1784,[9] and inventing the basis of modern refrigeration.

- ^ Thomson, John. An Account of the Life, Lectures and Writings of William Cullen, M.D. Volume 1. William Blackwood & T. Cadell, 1832, p. 1.

- ^ Thomson, John; Thomson, William; Craigie, David. An Account of the Life, Lectures and Writings of William Cullen, M.D. Volume 2. William Blackwood & Sons, 1859, p. 660.

- ^ Thomson, John. An Account of the Life, Lectures and Writings of William Cullen, M.D. Volume 1. William Blackwood & T. Cadell, 1832.

- ^ Doig, A., Ferguson, J. P. S., Milne, I. A., and Passmore, R. William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World. Edinburgh University Press, 1993, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ Waterston, Charles D; Macmillan Shearer, A (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index (PDF). Vol. I. Edinburgh: The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Bell, Whitfield J (1950). "Some American Students of "That Shining Oracle of Physic," Dr. William Cullen of Edinburgh, 1755-1766". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 94 (3): 275–281. JSTOR 3143563.

- ^ Doig, A., Ferguson, J. P. S., Milne, I. A., and Passmore, R. William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World. Edinburgh University Press, 1993, esp. pp. 40–55.

- ^ Bynum, W.F. and Porter, Roy. Brunonianism in Britain and Europe. Medical History, Supplement No. 8 (1988), pp. ix–x.

- ^ Doig, A., Ferguson, J. P. S., Milne, I. A., and Passmore, R. William Cullen and the Eighteenth Century Medical World. Edinburgh University Press, 1993, esp. pp. 34–39.