The Wright brothers patent war centers on the patent that the Wright brothers received for their method of airplane flight control. They were two Americans who are widely credited with inventing and building the world's first flyable airplane and making the first controlled, powered, and sustained heavier-than-air human flight on December 17, 1903.[1][2][3]

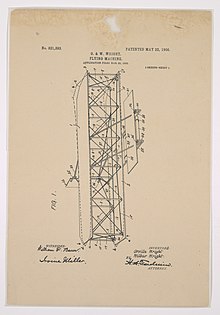

In 1906, the Wrights received a U.S. patent for their method of flight control. In 1909, they sold the patent to the newly-formed Wright Company in return for $100,000 in cash, 40% of the company's stock, and a 10% royalty on all aircraft sold. Investors who contributed $1,000,000 to the company included Cornelius Vanderbilt, Theodore P. Shonts, Allan A. Ryan, and Morton F. Plant.[4] That company waged a patent war, initially in an attempt to secure a monopoly on U.S. aircraft manufacturing. Unable to do so, it adjusted its legal strategy by suing foreign and domestic aviators and companies, especially another U.S. aviation pioneer, Glenn Curtiss, in an attempt to collect licensing fees.

In 1910, they won their initial lawsuit against Curtiss, when Federal Judge John Hazel ruled:

It further appears that the defendants now threaten to continue such use for gain and profit, and to engage in the manufacture and sale of such infringing machine, thereby becoming an active rival of complainant in the business of constructing flying-machines embodying the claims in suit, but such use of the infringing machine it is the duty of this Court on the papers presented to enjoin.[5][6]

Of the nine suits brought by them and three against them, the Wright brothers eventually won every case in U.S. courts.[7][8][9] Even after Wilbur Wright had died, and Orville Wright had retired in 1916 (selling the rights to their patent to a successor company, the Wright-Martin Corp.), the patent war continued, and even expanded, as other manufacturers launched lawsuits of their own—creating a growing crisis in the U.S. aviation industry.[8][9]

Many historians believe the patent war stalled development of the U.S. aviation industry,[8][10][11][12] but others dispute this claim.[13] Perhaps as a consequence, airplane development in the United States fell so far behind Europe[8] that in World War I, American pilots were forced to fly European combat aircraft instead.[14][15][16][17] After the war began, the U.S. Government pressured the aviation industry to form an organization to share patents.[8][18]

- ^ "The Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Johnson, Mary Ann (September 28, 2001). "Following the Footsteps of the Wright Brothers: Their Sites and Stories Symposium Papers". Wright State University. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ "Flying through the ages". BBC. 19 March 1999. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ The New York Times, Big men of Finance Back of the Wrights, (1909)

- ^ Wright v. Herring Curtiss. 177 F. 257 (C.C.W.D.N.Y. 1910)

- ^ James, Ricky. "Correlated Intellectual Property Rights". University of Helsinki, (2018) pp. 172.

- ^ McCullough, David (2015). The Wright Brothers. Simon & Schuster. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4767-2874-2.

- ^ a b c d e Roland, Alex (foreword by Jimmy Doolittle), Chapter 2: "War Business: A Laboratory and Licensing; Committees and Engines, 1915–1918", in SP-4103: Model Research: The National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics 1915-1958 - Volume 1, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 1983, retrieved December 4, 2017

- ^ a b Nocera, Joel (business columnist), Opinion essay: "Greed and the Wright Brothers," April 19, 2014, New York Times (citing Lawrence Goldstone’s new book, Birdmen), retrieved November 12, 2018)

- ^ Boyne, Walter J., aviation historian, former director/curator, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, "The Wright Brothers: The Other Side of the Coin", in Flight Journal magazine, as republished on Wings Over Kansas, April 20, 2008, retrieved December 3, 2017

- ^ Trainor, Sean, "The Wright Brothers: Pioneers of Patent Trolling," December 17, 2015, TIME Magazine, retrieved December 3, 2017

- ^ Nocera, Joe, op-ed: "Greed and the Wright Brothers,", April 18, 2014, New York Times, retrieved December 3, 2017, quoting Lawrence Goldstone's book Birdmen.

- ^ Katznelson, Ron; Howells, John. "The myth of the early aviation patent hold-up—how a US government monopsony commandeered pioneer airplane patents".Industrial and Corporate Change, Volume 24, Number 1, pp. 1–64 (PDF) Retrieved Jan. 24, 2016

- ^ Rumerman, Judy, "The U.S. Aircraft Industry During World War I," 2003, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, as archived by the American Aviation Historical Society, retrieved December 3, 2017

- ^ "Evolution of the Department of the Air Force," May 04, 2011, Air Force Historical Support Division, U.S. Air Force, retrieved December 4, 2017, quote:In the end the only American achievement in the field of aircraft production [in World War I] was the Liberty engine. Of the 740 U. S. aircraft at the front in France at the time of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, almost all were European-made.

- ^ Gropman, Alan, "Aviation at the Start of the First World War," 2003, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, as archived by the American Aviation Historical Society, retrieved December 3, 2017

- ^ Feltus, Pamela, "Air Power: United States Participation in World War I," 2003, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, as archived by the American Aviation Historical Society, retrieved December 3, 2017

- ^ "How The Wright Brothers Blew It," Nov 19, 2003, Forbes, retrieved December 3, 2017