| Zoroastrianism | |

|---|---|

| 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬀𐬌𐬌𐬀𐬯𐬥𐬀 | |

| |

| Type | Ethnic religion |

| Classification | Iranian |

| Scripture | Avesta |

| Theology | Dualistic[1][2] |

| Region | Greater Iran (historically) |

| Language | Avestan |

| Founder | Zoroaster (traditional) |

| Origin | c. 2nd millennium BCE Iranian Plateau |

| Separated from | Proto-Indo-Iranian religion |

| Number of followers | 100,000–200,000 (Zoroastrians) |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

Zoroastrianism (Persian: دین زرتشتی Dīn-e Zartoshtī), also called Mazdayasnā (Avestan: 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬀𐬌𐬌𐬀𐬯𐬥𐬀) or Beh-dīn (بهدین), is an Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the name Zoroaster (Greek: Ζωροάστρις Zōroastris). Among the world's oldest organized faiths, its adherents exalt an uncreated, benevolent, and all-wise deity known as Ahura Mazda (𐬀𐬵𐬎𐬭𐬋 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬃), who is hailed as the supreme being of the universe. Opposed to Ahura Mazda is Angra Mainyu (𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎), who is personified as a destructive spirit and the adversary of all things that are good. As such, the Zoroastrian religion combines a dualistic cosmology of good and evil with an eschatological outlook predicting the ultimate triumph of Ahura Mazda over evil.[1] Opinions vary among scholars as to whether Zoroastrianism is monotheistic,[1] polytheistic,[2] henotheistic,[3] or a combination of all three.[4] Zoroastrianism shaped Iranian culture and history, while scholars differ on whether it significantly influenced ancient Western philosophy and the Abrahamic religions,[5][6] or gradually reconciled with other religions and traditions, such as Christianity and Islam.[7]

Originating from Zoroaster's reforms of the ancient Iranian religion, Zoroastrianism may have roots in the Avestan period of the 2nd millennium BCE, but was first recorded in the mid-6th century BCE. For the following millennium, it was the official religion of successive Iranian polities, beginning with the Achaemenid Empire, which formalized and institutionalized many of its tenets and rituals, and ending with the Sasanian Empire, which revitalized the faith and standardized its teachings.[8] In the 7th century CE, the rise of Islam and the ensuing Muslim conquest of Iran marked the beginning of the decline of Zoroastrianism. The persecution of Zoroastrians by the early Muslims in the nascent Rashidun Caliphate prompted much of the community to migrate to the Indian subcontinent, where they were granted asylum and became the progenitors of today's Parsis. Once numbering in the millions, the world's total Zoroastrian population is currently estimated to comprise between 100,000 and 200,000 people, with the majority of this figure residing in India (50,000–60,000), Iran (15,000–25,000), and North America (22,000). The religion is thought to be declining due to restrictions on conversion, strict endogamy, and low birth rates.[9]

The central beliefs and practices of Zoroastrianism are contained in the Avesta, a compendium of sacred texts assembled over several centuries. Its oldest and most central component are the Gathas, purported to be the direct teachings of Zoroaster and his account of conversations with Ahura Mazda. These writings are part of a major section of the Avesta called the Yasna, which forms the core of Zoroastrian liturgy. Zoroaster's religious philosophy divided the early Iranian gods of Proto-Indo-Iranian paganism into emanations of the natural world—the ahura and the daeva; the former class consisting of divinities to be revered and the latter class consisting of divinities to be rejected and condemned. Zoroaster proclaimed that Ahura Mazda was the supreme creator and sustaining force of the universe, working in gētīg (the visible material realm) and mēnōg (the invisible spiritual and mental realm) through the Amesha Spenta, a class of seven divine entities that represent various aspects of the universe and the highest moral good. Emanating from Ahura Mazda is Spenta Mainyu (the Holy or Bountiful Spirit), the source of life and goodness,[10] which is opposed by Angra Mainyu (the Destructive or Opposing Spirit), who is born from Aka Manah (evil thought). Angra Mainyu was further developed by Middle Persian literature into Ahriman (𐭠𐭧𐭫𐭬𐭭𐭩), Ahura Mazda's direct adversary.

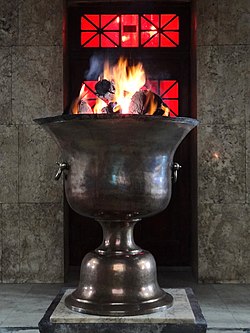

Zoroastrian doctrine holds that, within this cosmic dichotomy, human beings have the choice between Asha (truth, cosmic order), the principle of righteousness or "rightness" that is promoted and embodied by Ahura Mazda, and Druj (falsehood, deceit), the essential nature of Angra Mainyu that expresses itself as greed, wrath, and envy.[11] Thus, the central moral precepts of the religion are good thoughts (hwnata), good words, (hakhta) and good deeds (hvarshta), which are recited in many prayers and ceremonies.[5][12][13] Many of the practices and beliefs of ancient Iranian religion can still be seen in Zoroastrianism, such as reverence for nature and its elements, such as water (aban). Fire (atar) is held by Zoroastrians to be particularly sacred as a symbol of Ahura Mazda himself, serving as a focal point of many ceremonies and rituals, and serving as the basis for Zoroastrian places of worship, which are known as fire temples.

- ^ a b c Boyd, James W.; Crosby, Donald A. (1979). "Is Zoroastrianism Dualistic or Monotheistic?". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 47 (4): 557–88. doi:10.1093/jaarel/XLVII.4.557. ISSN 0002-7189. JSTOR 1462275.

In brief, the interpretation we favor is that Zoroastrianism combines cosmogonic dualism and eschatological monotheism in a manner unique to itself among the major religions of the world. This combination results in a religious outlook which cannot be categorized as either straightforward dualism or straightforward monotheism, meaning that the question in the title of this paper poses a false dichotomy. The dichotomy arises, we contend, from a failure to take seriously enough the central role played by time in Zoroastrian theology. Zoroastrianism proclaims a movement through time from dualism toward monotheism, i.e., a dualism which is being made false by the dynamics of time, and a monotheism which is being made true by those same dynamics of time. The meaning of the eschaton in Zoroastrianism is thus the triumph of monotheism, the good God Ahura Mazdä having at last won his way through to complete and final ascendancy. But in the meantime there is vital truth to dualism, the neglect of which can only lead to a distortion of the religion's essential teachings.

- ^ a b Skjærvø 2005, pp. 14–15: Ahura Mazdâ's companions include the six 'Life-giving Immortals' and great gods, such as Mithra, the sun god, and others [...]. The forces of evil comprise, notably, Angra Manyu, the Evil Spirit, the bad, old, gods (daêwas), and Wrath (aêshma), which probably embodies the dark night sky itself. Zoroastrianism is therefore a dualistic and polytheistic religion, but with one supreme god, who is the father of the ordered cosmos."

- ^ Skjærvø 2005, p. 15 with footnote 1.

- ^ Hintze 2014: "The religion thus seems to involve monotheistic, polytheistic and dualistic features simultaneously."

- ^ a b "Heard of Zoroastrianism? The ancient religion still has fervent followers". National Geographic. 6 July 2024. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Zoroastrianism". HISTORY. 5 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies | IRANIAN COSMOGONY & DUALISM | By: Gherardo Gnoli.

- ^ "Avesta | Definition, Contents, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Romey, Kristin (6 July 2024). "Heard of Zoroastrianism? The ancient religion still has fervent followers". Culture. National Geographic. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Spenta Mainyu | Ahura Mazda, Supreme Being, Zoroastrianism | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Angra Mainyu | Definition & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ The Moral and Ethical Teachings of the Ancient Zoroastrian Religion University of Chicago, pp. 58-59.

- ^ Masani, Sir Rustom. Zoroastrianism: The Religion of the Good Life. New York: Macmillan, 1968.